“I contend that the cry of Black Power is, at bottom, a reaction to the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary to make justice a reality for the Negro. I think we have to see that a riot is the language of the unheard.” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1966 TV interview with Mike Wallace

“Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1963, “I have a dream” speech

It was the first Facing Privilege teleconference after people started taking to the streets in response to the killing of George Floyd. I knew we would be engaging with what was unfolding in the US, because these calls are a space where people raise difficult issues and we engage with them, aiming for as much love and a liberation focus as we possibly can. And then Dave, a frequent caller and transcriber of calls, brought up the two quotes this piece starts with. He wanted to know how I would hold the tension between those two. The rest of this piece is edited from the dialogue that ensued.

I want to start with a huge caveat, which is I did not know Martin Luther King. I never had a conversation with him, and I don’t know what was inside him, what he was actually thinking and feeling. So everything that I’m saying here is conjecture. And I’m still going to say it. Because this is the best tool that I have: intuitive conjecture. I am going to guess that in these two statements, he is talking to two different audiences – whites and Blacks – for two different purposes.

I want to start with a huge caveat, which is I did not know Martin Luther King. I never had a conversation with him, and I don’t know what was inside him, what he was actually thinking and feeling. So everything that I’m saying here is conjecture. And I’m still going to say it. Because this is the best tool that I have: intuitive conjecture. I am going to guess that in these two statements, he is talking to two different audiences – whites and Blacks – for two different purposes.

“The Language of the Unheard”

The first quote – “A riot is the language of the unheard,” is meant for a white audience. He is attempting, poetically and succinctly, to get them to shift their frame, to appeal to their humanity, to invite them, quite intensely, to then see and have compassion for the humanity of the people whom they are referring to as engaging in “rioting” or “looting.”

At about that same time, I wrote a little bit about this in one of my Coronavirus pieces subtitled “Grounding in Interconnection and Solidarity.” I shared there a quote that I am sharing here again, because of how deeply important it is to me that complexity be understood and held. The quote is from David Sirota, a political consultant who has worked with the Bernie Sanders campaign: “Working class people pilfering convenience store goods is called ‘looting.’ While rich people stealing hundreds of billions of dollars is deemed ‘good public policy.’” What this complexity, and King’s initial interview, are calling for is a deep engagement at the systemic level to allow us to transform the entire story that’s folded into using the terms “riot” or “looting.” It’s a story in which one form of violence is made invisible, and responses to it are referred to as violence. Changing this story isn’t about “justifying” such responses; it’s about shifting out of the right/wrong paradigm altogether, and embracing a systemic perspective that allows us to see tragedy rather than assigning blame.

Since the call, and writing that piece, the initial protests exploded into a mass global event, linking people around the world in a spontaneous and unifying emergent process. As a participant in another call said since, there is a window now open for far more significant change than the single-issue focus on police brutality; a time when such brutality can be seen as merely a tragic symptom of the much deeper causes contributing to the unending assault on black- and brown-bodied people around the world. I am planning another article soon about more specifics related to the role of police in maintaining the social order, more about how capitalism and racism are inextricably linked, and how to think about change in this much wider picture while the attention and partial willingness are still there. For now, given the topic of this piece, I am only focusing on some relevant bits which explain the context within which people breaking into stores happens. This was true in King’s time. This is true today.

Since the call, and writing that piece, the initial protests exploded into a mass global event, linking people around the world in a spontaneous and unifying emergent process. As a participant in another call said since, there is a window now open for far more significant change than the single-issue focus on police brutality; a time when such brutality can be seen as merely a tragic symptom of the much deeper causes contributing to the unending assault on black- and brown-bodied people around the world. I am planning another article soon about more specifics related to the role of police in maintaining the social order, more about how capitalism and racism are inextricably linked, and how to think about change in this much wider picture while the attention and partial willingness are still there. For now, given the topic of this piece, I am only focusing on some relevant bits which explain the context within which people breaking into stores happens. This was true in King’s time. This is true today.

In an often quoted statement, Slavoj Žižek, a contemporary Slovenian philosopher, speaks to the invisibility of what he calls “systemic violence,” by which he is referring to “the often catastrophic consequences of the smooth functioning of our economic and political systems.” When the violence inherent in these systems is not acknowledged – as it rarely is in the mainstream narrative – the actions of some of the protestors can easily be seen as disproportionate, as if they are coming out of the blue, as if they are more a statement about the people taking the actions than about the systems that have consistently failed them in gross and wrenching ways.

Žižek devoted an entire book to explorations of violence, and it takes quite a bit of exposure to education to be able to read and make sense of this book. A much shorter route to grasping the calamity is a video lasting under seven minutes which to me drives home the point in a way that is unforgettable. This is a short speech titled “How Can We Win” by Kimberly Jones, co-author with Gilly Segal of the young adult novel I’m Not Dying with You Tonight. Almost two million people have viewed this video, and for once I fully understand why a piece went viral. I found every second of it compelling to the bones. Jones turns the question of looting on its head. Instead of trying to answer the question of what they are doing, she is focusing on why they are doing it. She calls attention to what it would take, how much suffering, disenfranchisement, and cumulative powerlessness would have to exist for some people to see walking through a broken glass window into a store as their only chance. Jones invokes the metaphor of a rigged monopoly game running for hundreds of times where one side receives no money for the game, and anything they generate goes to the other side, as a way to describe the centuries of slavery. Then, when despite all this, some Blacks managed to build their own fortunes, those were usually wiped out violently. This is a piece of US history many more people don’t know than do. As a recent article in the Guardian chillingly summarized: “Black economic success, particularly when juxtaposed against white economic struggles, has historically been a catalyst for violence.” One of the worst such episodes happened in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921. Tulsa was then home to what was called “Black Wall Street” – and it was wiped out overnight by a white mob supported by airplanes dropping incendiary devices.

Again from the same article: “In less than 24 hours, a white mob reduced a vibrant, 35-block area to rubble and dead bodies.” Lest anyone thinks this is ancient history, in 1985 a smaller scale aerial attack on a black neighborhood also happened, described in another Guardian article. Delving into the history of race relations in the US is a sorrowful activity, and much faith in humanity is needed to be able to emerge from such explorations and still believe that anything positive is even possible.

Again from the same article: “In less than 24 hours, a white mob reduced a vibrant, 35-block area to rubble and dead bodies.” Lest anyone thinks this is ancient history, in 1985 a smaller scale aerial attack on a black neighborhood also happened, described in another Guardian article. Delving into the history of race relations in the US is a sorrowful activity, and much faith in humanity is needed to be able to emerge from such explorations and still believe that anything positive is even possible.

Understanding the systemic context that brings about these tragedies happen is the only thing that repeatedly replaces the shock and terminal alienation I feel in relation to those doing those harms with grief, just unending grief for all that has befallen us since the initial calamities that led to the establishment of patriarchy in Europe.

King’s quote speaks of “the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary to make justice a reality for the Negro.” Beyond those who have the power to make decisions that affect billions, I continually wonder how many of us, individuals who have access to and benefit from light-skin privilege, would be truly willing to part with at least some of it in order for our darker-skinned sisters and brothers to have a baseline of dignity, material safety, and care. I wonder about all of us with this privilege, whether or not we also have white belonging (which Jews and white immigrants don’t); whether or not we also have significant wealth; whether or not we also have knowledge of the history that got us here; whether or not we also know the continued and persistent practices and narratives that still target and assault darker skinned, and especially Black people.

I also know that it won’t ever be up to a collection of individuals to create the massive changes necessary, and that if and when the entire edifice of patriarchy, and with it capitalism and white supremacy, collapse, maybe then something else can happen. After all, it was the failed state of Syria that is the birth place of the most democratic, bottom-up, region in the world, where de facto no state exists: the autonomous region of Rojava, the only place in the world that on the scale of millions calls itself feminist, right in the same region where the earliest patriarchal states from which European history as we know it directly descends were erected.

I am heartened to see that protests against police brutality and calling attention to anti-blackness are now taking place in towns and regions in the US that would never have been part of such events in the past, and in many countries around the world. The road is far to reach a destination of “beloved community” and still there are signs that something new is happening.

It is white people, those of us with that privilege, those of us who are more exposed to the mainstream narrative that makes what’s happening appear like “looting,” that King was addressing in his first quote. He was inviting us to look more deeply, to open our hearts. And once we do, nothing within me can make sense anything less than compassionate, heartbroken understanding of why people who have been trodden upon would rise up. I quote Kimberly Jones here: “they are lucky that what Black people are looking for is equality and not revenge.”

“Meeting Physical Force with Soul Force”

Again I want to remember that I don’t know what King actually thought and intended. I can only guess, and I believe that his second quote was addressed, primarily, to the Black community, to the people active in the Civil Rights movement and to their direct supporters. It is a bit beyond my imagination to grasp the moral and political courage that Dr. King possessed to tell people, basically, “I fully understand why you would want to respond with physical force. And I implore you to use soul force instead.” I am sensing that the only way that he could do that is because he had sufficient faith in the power of soul force.

The power of soul force is unlike any other power, because it is moral power that operates at the level of soul. He wasn’t, in any way, trying to imply that if you use soul force, it will protect you from someone shooting you and killing you. He wasn’t trying to imply, as far as I can tell, that using soul force means you can actually force anyone to do anything. What soul force does, instead, is to make it morally and politically untenable for those who are in positions of ultimate power to continue to uphold their power. This was his idea about how to respond to “the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary to make justice a reality for the Negro.” No external force would ever be enough for this, and, if it ever were, the result would not be beloved community. Based on my reading King and Gandhi, reading about them, and listening to some of Dr King’s speeches, I am quite certain that they both fervently believed that if anything could create the full transformation they were longing for – which in today’s terms I would name liberation for all – it would only be soul force, never physical force, though they both knew well that the goal of full, pure nonviolent means was unattainable within the flow of life; that all we can do is minimize forever the amount of force and increase forever the amount of love, as I wrote about in my article “Is Nonviolent Use of Force an oxymoron?”

So how does soul force actually work?

Its success depends on specific changes that would happen in relation to three specific groups: the public, the army and police, and those who hold the ultimate power to make decisions that affect the rest of us.

The public, generally speaking, ranges from those who are sympathetic to the cause of the protest to those who are upholding the status quo. As King clearly knew, and Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan demonstrated in their work on nonviolent resistance, massive public support is vital for creating change, and nonviolent resistance is far more likely to garner public support than any kind of violent responses. And while disputes about whether property damage is or isn’t encompassed within nonviolence continue, it is clear that the uninvolved public does see it as violent.

I want to stress this again, because it’s too easy to forget or re-interpret what we know about the wrenching history of the US. In the US, protests that erupt into what the Civil Rights Digital Library refers to as “urban rebellion,” are invariably the result of one more incident in a long chain of what remains largely invisible to the majority of white people, including to those who are generally in favor of equality. No incident that happens to any Black person in the US is ever an isolated event. Every reaction is within the context of the entirety of the last several hundred years. And yet to others it is portrayed as a violent, out-of-the-blue eruption of violence that says more about those protesting than about the conditions that lead to such protest.

I want to stress this again, because it’s too easy to forget or re-interpret what we know about the wrenching history of the US. In the US, protests that erupt into what the Civil Rights Digital Library refers to as “urban rebellion,” are invariably the result of one more incident in a long chain of what remains largely invisible to the majority of white people, including to those who are generally in favor of equality. No incident that happens to any Black person in the US is ever an isolated event. Every reaction is within the context of the entirety of the last several hundred years. And yet to others it is portrayed as a violent, out-of-the-blue eruption of violence that says more about those protesting than about the conditions that lead to such protest.

The history is rarely known. That the last state to cross out “miscegenation laws” preventing Blacks and whites from marrying each other was Alabama, and that it happened only in 2000, is likely a surprise even to many white people reading this blog, who are mostly educated people with a critical outlook on the mainstream order. Similarly, how many of you reading this post know that there have been many thousands of “sunset towns” across the US, or even know what they are? These were towns where everyone knew that Black people had to leave before sundown, or their life was not assured until the next morning. And many if not most of them were in Northern states that claim to have abandoned their racist past. And they are not entirely a thing of the past, though outright violence against Black people by residents is far less common than it was; it’s the police who now carry it out.

This history being unknown, and the general predilection for assigning the status of “violence” to property damage, is why I believe that King’s second quote is to those who do know that history, who are actively protesting against it, putting their lives on the line either because their own lives are in the context of this pervasive violence, or in solidarity, when they risk social ostracism.

It is based on the understanding that, in the context I just painted, the more the protestors are able to mobilize the deep, uncompromising commitment to nonviolence as they insist on the fullest transformation they can envision; and the more willing they are to absorb physical force and respond only with soul force, the more credibility they will have with the public. The sight of police, in full riot gear, launching an unprovoked attack on what are called “peaceful protestors,” as happened in New York City, is upsetting to many more people than seeing police use the exact same methods when fires and broken glass are in the background. Knowing this, King, and Gandhi before him, urged their followers to refrain from anything that could be seen as violence even as those in the movements walked straight into breaking the law as necessary (salt march, lunch counter sit-ins) without creating any physical harm. This willingness to absorb violence without dishing it back is core to the power of nonviolence, because it “forces” people to recognize the irreducible humanity, the dignity, and the moral strength of those embracing this code. Many stories from the Civil Rights era and elsewhere speak to this power. Just remember Antoinette Tuff, whose calm and love averted a school shooting, as documented in this Guardian article, and there is no denying that there is something powerful at work here.

It is based on the understanding that, in the context I just painted, the more the protestors are able to mobilize the deep, uncompromising commitment to nonviolence as they insist on the fullest transformation they can envision; and the more willing they are to absorb physical force and respond only with soul force, the more credibility they will have with the public. The sight of police, in full riot gear, launching an unprovoked attack on what are called “peaceful protestors,” as happened in New York City, is upsetting to many more people than seeing police use the exact same methods when fires and broken glass are in the background. Knowing this, King, and Gandhi before him, urged their followers to refrain from anything that could be seen as violence even as those in the movements walked straight into breaking the law as necessary (salt march, lunch counter sit-ins) without creating any physical harm. This willingness to absorb violence without dishing it back is core to the power of nonviolence, because it “forces” people to recognize the irreducible humanity, the dignity, and the moral strength of those embracing this code. Many stories from the Civil Rights era and elsewhere speak to this power. Just remember Antoinette Tuff, whose calm and love averted a school shooting, as documented in this Guardian article, and there is no denying that there is something powerful at work here.

The strength of this force is even more pronounced in relation to army and police, the people who are supporting the status quo with their own lives on the line. They are, more often than not, working class people with few options. They are supporting the institutions, without being of them. This is part of the paradoxical nature of things. Since their loyalty is primarily instrumental, and not based on true alignment with those who, ultimately, rule their own lives too, the use of soul force makes it progressively more difficult for the army and police to carry out their duties in support of the status quo.

To me it’s both more astonishing and entirely obvious. When I try to imagine myself being a police officer, or a member of the military, with a protester throwing a rock at me, I will feel much more justified in continuing to oppress that person than not. Even just the absence of any provocation is challenging. One of the reasons why the Nazis shifted from mass shootings to gas chambers was that the officers charged with shooting had to be replaced frequently, because they couldn’t continue shooting and killing large number of unarmed people day in and day out. Violence against another person must be internally justified in order to be enacted. Peaceful protestors don’t provide sufficient justification over time to attack them, and the strength of support for the powers that be diminishes.

And this even before soul force fully enters the picture. Back to the picture in which I am the police officer, soul force goes far beyond a protestor passively letting me assault and hit them. It means, in the deepest places possible, that the protestor reaches for my humanity, for my heart and soul, with the faith that I have a heart and a soul, that I am no different, ultimately, than they are. This unwavering faith, this appeal to my humanity, will “force” me gradually to lose my ability to keep oppressing the protestor. The power of soul force is the insistence on waking up the empathic, latent, numbed out, submerged human soul of the police and the army. This also explains why the George Floyd killing was so profoundly unsettling. If Derek Chauvin had looked scared or even frothing with anger, it would have been more understandable even if equally upsetting in terms of loss of life and the systemic context. It’s the casualness, the indifference, the inability to take in and be affected by George Floyd’s last words, by the direct appeal to Chauvin’s humanity, that is so profoundly shattering to our sensibilities, that is so frightening to me in terms of where this colossal empathy collapse emerges from. Have we created a collective monster that makes appeals to empathy futile? Still, the faith in the power of soul force remains, perhaps our only hope.

Soul force first affects and changes the person stepping into it. The courage, imagination, strength, and inner freedom that it both takes and generates are hard to even put into words. Then, as I just laid out, soul force shifts public attitudes and potentially wakes up and touches the humanity of those charged with maintaining, physically, the existing order.

Lastly, soul force operates in a third area, the arena of the powerful. This requires the most difficult leap of faith. In a piece I wrote some years ago, called “Pushing the Powerful into a Moral Corner,” I argued that part of the strategic strength of nonviolence, of soul force in particular, is that we are calling on the powerful to adhere to their own values. In the case of Gandhi, he had intimate knowledge of British culture, and used it in how he engaged with them. His appeal to their humanity, a well-known core aspect of his approach, most likely rested on “a gentlemanly attitude, being civilized and reasonable, being seen as decent. By both being treated with dignity and being recognized as caring about dignity, the British were pushed into a moral corner in relation to their own values and invited into living in integrity with such values.” In the case of the Barefoot College, the contemporary institution about which I wrote, they are pushing on the government’s own laws.

In order to appeal to the rulers’ humanity we must understand their humanity, their sense of self, what matters to them, not to us. Only then can we push them with the moral imperative that soul force presents. This is one part of how Gandhi and the movement he inspired drove the British out, and did so, as historian Arnold Toynbee noted, without rancor. Soul force pushes the powerful to feel the tension between what they’re doing and their professed values.

In order to appeal to the rulers’ humanity we must understand their humanity, their sense of self, what matters to them, not to us. Only then can we push them with the moral imperative that soul force presents. This is one part of how Gandhi and the movement he inspired drove the British out, and did so, as historian Arnold Toynbee noted, without rancor. Soul force pushes the powerful to feel the tension between what they’re doing and their professed values.

At a time when empathy has been on the decline in the US, and the person in the highest office in the US is fanning racial hatred, prospects for soul force could feel meager. And yet… this all is happening at the time of a pandemic that is already documented to have enhanced empathy and compassion. Perhaps this increase in empathy coupled with the reality that violence has been quite contained and, more often than not, apparently instigated by police, are having the exact effect I would anticipate. Perhaps this is why even small rural towns, including some specifically known to be strongholds of racism, have seen protests, as documented in this article in the Washington Post. Perhaps the power of soul force is breaking through finally, and the long arc of history is beginning to bend. May it be so.

Photo credits:

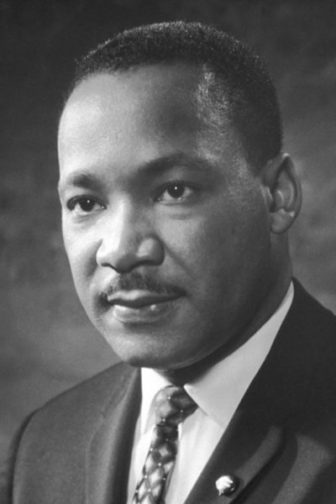

Martin Luther King: Author unknown, Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martin_Luther_King,_Jr..jpg

Broken Glass: Pixabay, free to use (CCO),pexels.com/photo/black-and-white-broken-dark-glass-235727/

Tulsa, 1921: Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tulsa_race_riot_inflames-1921.jpg

Force Disabled: Pikist, free to use, www.pikist.com/free-photo-xpzse

Hands in chains: PXfuel, royalty free prison photos,www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-jmwmz

Peaceful Protestors: Author Carol Moore DC, Wikimedia Commons, Nonviolence Protesters 04-16-00

Gandhi: Pixabay, free for commercial use: pixabay.com/photos/mohandas-karamchand-gandhi-67483/