“If we agree to accept limits on who is included in humanity, then we will become more and more like those we oppose.” – Aurora Levins-Morales1

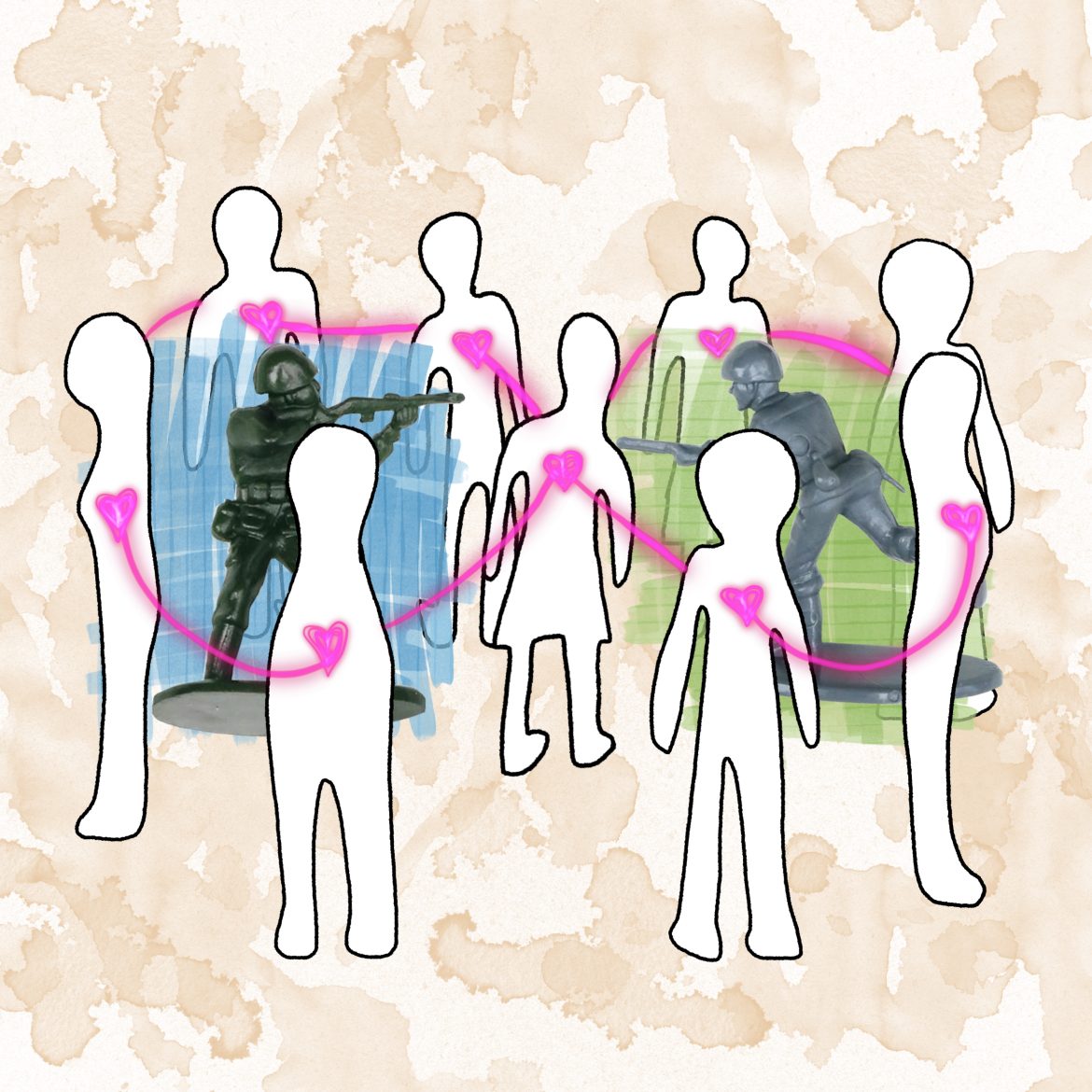

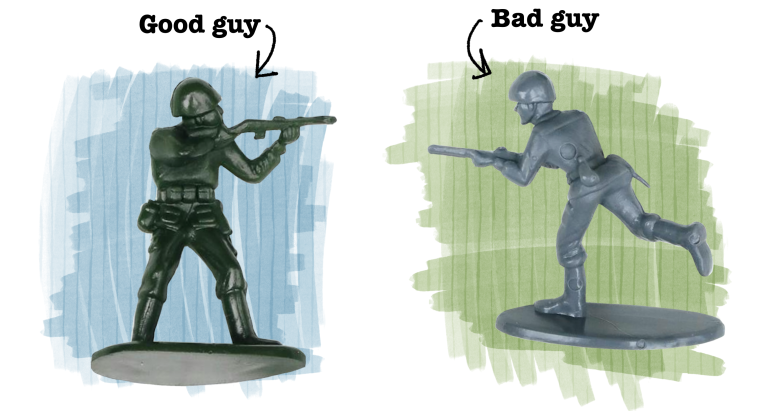

For as long as there are “bad guys”, wars will continue. War, as I understand it, is a state of collective active willingness to kill or be killed using arms. For every war, some identify with one side, some with the other side, and some mourn there being war at all and want solutions that care for everyone’s needs.

This startling move of caring for all needs humanizes everyone and is the heart of nonviolence.

Its radical premise is that all humans, no exceptions, have the same needs in four areas: physical needs, freedom, connection, and meaning. Even if we stand up to those who kill, maim, or starve others, we can stay human together and understand those horrors as distorted expressions of real human needs born of tragedy.

War cannot be “won”. Imposed outcomes suppress needs and feed the longing to take power back and make winners lose, all of which seed future wars. Jim Crow and WWII were, in part, reactions to imposed outcomes on Southern whites and Germans, respectively.

Palestinians and Israelis are no exception: imposing solutions on either of them will backfire. Instead, seeing all violence as emerging from real human needs makes possible and practical the uncompromising commitment to care for all needs. When trust in each other’s humanity is restored, and when care and goodwill begin to flow, the creativity and wisdom that our big brains are capable of is astonishing. This is what we see when, on a small scale, Palestinians and Israelis are brought together in supported processes: they regularly find pathways for friendship and mutual care.

Surrounding the patriarchal field with love

Between 1900 and 2015, nonviolent uprisings succeeded twice as often as violent ones and far more often resulted in democratic outcomes.2 Partly, it’s because it’s much easier to engage with nonviolent movements. A second factor is the moral force of nonviolence integrated deeply enough to where we fully “REFRAIN from the violence of fist, tongue, or heart.”3 This orientation makes it more difficult to repress nonviolent movements and eventually leads some regime supporters to defect.

Force, even if we ever had it, will not bring about trust, goodwill, creativity, empowerment, or flow. Instead, surrounding the patriarchal field with an even larger field of love so we uphold and appeal to the dignity of those we stand up to, may well be our only hope for realigning with life.

I believe it is up to those of us who live outside the region to create this field of love without expecting those within the region to bring tenderness and understanding to each other’s experiences and actions.

Finding love starts with mourning, understanding, and vision. Mourning is responding to the incomprehensibility of war the way a small child would: crying our hearts out at what simply hurts until we find capacity to be with what is – without narratives about who is right, what is fair, and what should happen – and begin to understand everyone again and restore our imagination about alternatives.4 Then we can align means with ends for a nonviolent response to war, without recreating the logic of war.

Nonviolence rests on three pillars: courage, truth, and love. Courage is necessary for undoing our adaptation to the patriarchal mindset of scarcity, separation, and powerlessness, so we can willingly face the consequences of taking a stand for life, for everyone’s life. This may include revising everything we ever believed, accepting reactions from friends and family, or, if we persist, loss of access to resources, legal consequences, and, in certain contexts of escalation, even death. We stand in harm’s way without lashing out at anyone.

Courage prepares us for the simple and difficult aspect of truth within nonviolence: nonreactive discernment based on self-trust and in full integrity with what is true for us in terms of vision, values, and purpose.

Nonviolence reaches its full loving radicality when we let nothing interfere with remembering that everyone was born and remains kin and wishing them well. It’s a deep faith that everyone would prefer to care for what matters to them without harming others if they could see a way to do that.

This means understanding why Hamas chose to attack Israel – without excusing or justifying them; being horrified at such actions – without condemning them; understanding Zionism as a tragic both/and: a form of settler colonialism and a national liberation movement – instead of seeing only one aspect and not the other. It means grasping that atrocities are done by humans sufficiently traumatized to inflict harm on each other5 and taking in that anyone born into the other side would likely act like the other side does now – without forgetting the immense power differences that make harm caused by Israelis incomparable with harm caused by Palestinians.

Nonviolence means wishing for both Palestinians and Israelis what they need to live and thrive in what they both experience as home, alongside each other, in a togetherness we may not yet be able to imagine.

Stopping war once it’s started

Within patriarchal logic, attending to conflict includes potential violence, such as murder, violent state repression, and war. And while nonviolent alternatives exist within states, nonviolent alternatives to diplomacy and war are generally deemed unfeasible. Despite this, a small group of us have taken initial baby steps to start the Women in White project to do exactly that.

Here are excerpts from the vision that is at the heart of this project:

Imagine 100,000 women dressed in white coming to a war zone. Imagine them forming a nonviolent human shield. … Imagine them standing together to protect everyone, regardless of “side”, political affiliation, or national identity. They are … determined to use the power of nonviolence to call everyone back to their humanity. They have trust in their capacity to stop the war and create a foundation for a peaceful approach to addressing the conflict that led to the war. They act as one body, rooted in nonviolence, loving life, vital, and full of faith. … They will need extraordinary trust in life to believe that rulers, generals, soldiers, and guerilla fighters will be transformed by their large numbers, as women, and only women, and that their love for all, including those who harm, will be enough to stop the shooting.

An all women group. We believe women are more likely to remain nonviolent and to bring fighters back from the trance of war and less likely to be shot at. We are particularly inspired by several thousand women in Liberia who brought an end to civil war through loving nonviolent protest.6

We similarly need collaborative and distributed means based on human ingenuity, trust, and relationships for the vast engineering challenge of moving 100,000 women across the globe to where war is raging. We believe that women are more likely to design web-like, interdependent, and locally creative pathways for these challenges.

Large numbers. We believe even a large army or guerilla group, when faced with such a large field of love, will lose capacity to dehumanize and inflict violence.

Moving without urgency. Our focus is on building capacity and faith for the long haul. This means reweaving severed relationships and communities sufficiently for spirit and vision to travel far. It means challenging patriarchal socialization and building a coherent microcosm of our vision to work out resources, coordination, crossing borders, and ongoing emergent needs. With mourning, we accept that the current war will unfold as it will regardless of what we long for.

Finding solutions that work for everyone (or just about)

The war narrative asserts that if we punish, displace, or kill the “bad guys” sufficiently, the rest of us, the “good guys”, can breathe in relief and maintain a peaceful life. In the context of the current war, this leads some to hatred of Jews as the perennial settler colonialists and some to hatred of Palestinians as the perennial terrorists.

Would countering the essential logic of separation and weaving togetherness, based on what’s important to everyone, make it possible to find solutions that actually work for previous adversaries? This – though not in the context of war – is what Convergent Facilitation was specifically designed for: collaborative decision making even in difficult situations based on creating a mini field of love through applying rigorous principles and specific skills and leaning on trust in life.7

It starts with establishing goodwill through identifying noncontroversial principles and needs underneath the clashing concerns, desires, opinions, actions, preferences, and habits that make us forget each other’s humanity within conflict and war.

Here’s an example from a Palestinian perspective. The statement “From the River to the Sea, Palestine shall be free” is controversial for almost all Israeli Jews. Could the following capture it sufficiently and still be acceptable to everyone?

- Full participation for Palestinians in shaping social arrangements in the region

- Full freedom of movement for Palestinians anywhere in the region and beyond

- Restoration of dignity for Palestinians

And here’s one from an Israeli perspective. The statement, “Israel shall remain a Jewish state” is controversial for just about any Palestinian and even some Israeli Jews. And, again, could the following capture it sufficiently and still be acceptable to everyone?

- Proactive care for the ongoing physical existence of Jews in the region

- Maintaining a clear home in the region for all Jews

- Supporting the cultural and linguistic elements of Jewish life

Even if these principles are enough for most, if we want a solution that works for everyone, not only for the moderates, it becomes essential to invite and integrate dissent and concerns from extremists on both sides. Otherwise, those left out become, yet again, the seed of more violence.

Even when those on the extremes boycott the process altogether, we can still find ways to take in and integrate the needs within their deep concerns and charged views.

This principle has no exceptions. It includes those calling for killing Palestinians as well as those calling for killing Jews. It means excavating, from within horrifying rhetoric, basic needs important enough to overshadow care. It means trusting the power of being heard to de-escalate conflict, true no less of extremists than of anyone else.

Once we have one interdependent list of all the considerations, principles, and needs, it supports sufficient trust and goodwill for everyone to participate in creating the future together. Beyond what’s “fair”, either/or, or debates, we can embark on a creative, generous, and inspired search, based on the list, for what can work for everyone. This doesn’t mean everyone is happy and comfortable; only that everyone is willing because they see that this is far better than their preference being imposed on others.

What could such a solution look like? We don’t and can’t know what happens when we tap into and unleash creativity within real-life constraints.

And, still, even as we can’t know, a potential solution to a deeply distressing dilemma – the struggle over the “right of return”– found me spontaneously when I was pondering a deep challenge within it that has haunted me for years: what is possible when a Palestinian family wants to move into a house in which an Israeli family now lives?

From within a Convergent Facilitation perspective, I understood that staying close to actual needs, impacts, and resources, families can be supported to assess and make the wrenching decisions together, on a case-by-case basis, about when it makes sense for the Israeli family to move elsewhere and for the Palestinian family to move in and when it makes sense for the Israeli family to stay and for the Palestinian family to find another home. Either way, this solution may inspire resources for both families. And this may be less utopian than imagining that an imposed solution, on either group, wouldn’t lead to escalating violence.

Some of us are actively thinking, even while the war is still raging, about starting an informal Convergent Facilitation process, through existing connections, with a wide enough range of perspectives in who we connect with, that the moral force of an outcome endorsed by all may become unstoppable, as has happened before.

Restoring resilience when everyone is a victim

“When I was young they told me if a generation of people got pushed to killin’ other people, it took four generations of peace to get peoples’ heads fixed afterwards. And we hadn’t had them four generations…” – As told to Anne Cameron8

If war is not inherent to human nature, then it likely emerges from trauma which begets further trauma which then leads to more war. The significant trauma I see as the seed of further war is relational: the shock and loss of trust that come from seeing fellow humans dehumanize us and act violently towards us. Tragically, we often react to this by dehumanizing those who dehumanize us. I see this as the most vitally important trauma to address when the material dust of war settles.

Trauma is relieved by restoring resilience, not by punishing anyone. I see resilience as the renewed capacity to experience new impacts without automatically reverting to separation. It happens, spontaneously, when everyone is supported to experience, again, the humanity of all involved, and to release protection. This may well be what interrupts the cycle of violence.

As far as I know, this awareness of everyone having been traumatized has not happened within any field of war or other massive violent conflicts. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) formats, most famously in South Africa and Rwanda, are the closest, and have indeed restored baseline capacity to function into devastated societies. And I don’t think they go far enough to challenge and fully transform retributive frames.

Within massive conflicts, their internal logic is painfully simple: “Our actions against you”, says each side, “are justified, or even caused by what you did to us.” Every act of violence, says prison psychologist and author James Gilligan, is an attempt to create justice and to right a wrong. This includes interpersonal violence, the criminal justice systems, and war.9

Countering this deeply grooved path requires, again, love. Love can make it possible to recover from horrors and walk what some have called “the long road from truth to reconciliation”. This shift at the moral and spiritual plane makes possible reestablishing togetherness where it has been destroyed through violence. This is love as deep care for everyone’s humanity and dignity, love courageously integrated with truth.

The evidence that full reconciliation is possible is simultaneously sparse and compelling. It includes a small-scale process Marshall Rosenberg conducted in the early 1990s in Northern Nigeria where a bloody conflict had claimed 100 of 400 lives. He supported each group to hear and understand the other group’s pain and the needs that gave rise to it. As each person who spoke was fully received with expressions of empathy, acknowledgment of impact, and mourning of the suffering, protection receded and hearts opened. One of those present eventually exclaimed: “If we know how to talk to each other this way, we don’t have to kill each other.”10

It also includes dozens of accounts about people turning away from violence and hatred based on immense and sometimes inexplicable acts of love towards them, including Ku Klux Klan active members or a would-be school shooter. Such unfamiliar love leaves behind the false either/or of severe punitive responses or doing nothing.

Whenever possible, reconciliation processes bring people together to restore their sense of each other’s humanity. Through empathy, acknowledgments, mourning, and vulnerable expression, we remind everyone that war happens because we have been traumatized – through socialization, through living within scarcity, separation, and powerlessness, and through direct trauma – making it tragically easy for us to see others’ existence as a threat to ours. As trust is slowly restored and those whose actions led to impacts see, again, the humanity of those they have harmed, they also open to the horror of what they have done and can make understandable the human experience and needs that led to their actions. Worlds apart from “exoneration”, the full weight of what happened and the responsibility to care for impacts then become more possible.

And sometimes there simply isn’t enough capacity for direct engagement and surrogates may be needed. Marshall Rosenberg supported thousands of people – including many who survived serious abuse and even some who survived what happened in Rwanda in the 1990 – to heal from immense trauma by impersonating those whose actions led to the impacts.

When millions are impacted and millions are at least accepting acts done in their name if not actively condoning them, it is impractical for everyone to participate in active dialogue. How, then, could such a process unfold when restoring togetherness is essential to dramatically reduce the chances of a new cycle of war?

Could the following fictional example serve to inspire others?

A random sample of one hundred Gazans are invited to speak about impacts on them to a Binyamin Netanyahu surrogate.11 One by one, they share stories about what has happened to them, to their families, to their neighbors, to their communities, to their institutions, and to the infrastructure of their towns, and what has impacted them as human beings. As each one speaks, Netanyahu’s surrogate offers empathy to show that he gets the impacts and then acknowledges his actions and mourns the horror that they have inflicted on Gaza. When all of them have experienced the relief that comes from being understood and from seeing the mourning, and only then, he speaks of what has actually led to his choices to make them humanly comprehensible. It is through humanizing him and others – however long it takes to fully integrate this radical shift – that we exit the vortex of war as the field heals from the depth of separation that would otherwise prepare the ground for the next phase of war.

When this phase is done, we repeat it in the other direction. A random sample of Israelis share their stories of what happened to them and others on 7 Oct 2023 with a surrogate for whoever then leads Hamas. And when that phase is done, the next phase is, again, turned around. This time the impacts are in relation to what happened before that fateful day, the years of siege and dehumanization that Gazans had been through. And this continues backwards in time to weave a human foundation for a different future. Simultaneously, everything is televised and streamed globally to support healing and repair of the wound within the human field that this and all other wars have created.

Instead of making any statements about what is more or less important – which is still trying to make sense of war from within its logic– the choice about where to start is about what is more or less current. Going backwards in time supports the possibility that the material and emotional connecting of dots will arise, organically, through learning about and metabolizing all impacts within the slowly emerging togetherness.

In my wildest dreams, this would continue backwards, everywhere in our collectively devastated global home, until the earliest invasions and even before, to the original disasters that started patriarchy and war. Might this reverse our march to extinction?

Not an end: looking at what we can do

We haven’t gotten any smarter about responding to war despite having an average of 150 armed conflicts every year, and no year without armed conflict in centuries. No heads of state, UN officials, or marchers know how to get us to a path of reconciliation. Usual ceasefire agreements are fully within the logic of war. The Women in White project is embryonic and years away from being a significant player. And the conditions for a serious application of Convergent Facilitation or impact sharing are not yet in place.

When the longing for realigning humanity with life meets this present reality, the suffering is immense, even when our actual individual lives are comfortable. What we can do is to integrate a focus on vision with mourning the gap to keep our heart open and soft and with finding clear action within our sphere of influence. However small or inadequate it might be, this is where we do have the capacity to make something happen. This focus led me to the Women in White project and to writing this article.12

And what is yours to do, within your sphere of influence? I long for each of us to take seriously our conditions, our strengths, the limitations that impair our capacity, look for openings within our sphere of influence, take in the external obstacles we face, and find what is ours to do within our context. What would you do if you accepted the risks that come from speaking truth with love? What matters is that we mobilize in full to follow our heart, integrity, and intuition, even if only to bring tenderness to our limitations instead of succumbing to shame and guilt.

Just like forced solutions don’t bring an end to war, forcing ourselves or others to mobilize won’t result in paradigm shifts. Wherever we are, whatever we do or don’t do, I want to surrender to the hope that it may still be possible for some of us to find a path that many of us can walk to bring an end to war through integrating power and love.

1 See Medicine Stories: History, Politics, Integrity

2 Erica Chenoweth, “The Rise of Nonviolent Resistance”, 2016, https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/PRIO-The%20Rise%20of%20Nonviolent%20Resistance.pdf

3 https://www.bhamwiki.com/w/Nonviolence_pledge

4 When I did that, shortly after 7 October 2023, it led to coordinating the writing of a statement about the war called “Responding to War with Love: Stitching the Middle East at the Heart Level”, which was all about mourning, understanding, and vision

5 See my article “The Freedom to Disobey”

6 Their story is documented alongside the violence they managed to stand up to in a film that I found at once disturbing and moving called Pray the Devil Back to Hell.

7 See https://convergentfacilitation.org/case-studies and my book The Highest Common Denominator, for a number of significant examples

8 See Daughters of Copper Woman

9 The first two points are elaborated and illustrated quite dramatically in his book Violence: Our Deadly Epidemic and Its Causes.

10 A longer version of this story appears in Speak Peace in a World of Conflict, pp. 121-125.

11 While in theory he himself could be prepared to hear the impacts, the likelihood of that seems exceedingly small.

12 A much longer version of this article can be found here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1h7xd38zdej4L5mu1ot8WkBoHvLPvSJ8MA7Tf7pRFfoU/edit

Image Credits

These collages and illustrations were created by Gwen Olton (@kooolgwen) and using images from:

- Plastic Toy Soldiers , Group of Military Miniatures , Collection of Plastic Toy Soldiers , photos by Polina Tankilevitch at Pexels

- “Door key” , photo by Maria Ziegler at Unsplash

- “My model of T-34/85 tank in 1:35 Revell” , photo by Matias Luge, at Unsplash

- “Military Medical Helicopter” , photo by Aleksandar Popovski , at Unsplash