On October 22 of 1883, Frederick Douglass attended a civil rights meeting in Washington D.C. where he observed a disturbing pattern of hatred that disempowered Americans showed toward their Black countrymen: “Perhaps no class of our fellow citizens has carried this prejudice against color to a point more extreme and dangerous than have our Catholic Irish fellow citizens, and yet no people on the face of the earth have been more relentlessly persecuted and oppressed on account of race and religion than the Irish people.”

Douglass singled out Irish immigrants, but the phenomenon he noticed was not unique to this group. What he condemned was the all-too-common failure of civic imagination – the reluctance to acknowledge a shared humanity and reach out to the oppressed still struggling to gain full citizenship in a society plagued with prejudice and injustice.

This pattern has persisted over time and is now evident in the anti-gay stance taken by the Frederick Douglass Foundation. According to Clarence Henderson, head of the North Carolina chapter of this conservative African American organization, “there’s no comparison” between the LGBTQ fight for gay rights and the African Americans’ struggle for civil liberties. “How many gays or lesbians were lynched?” asks Henderson. “There is a difference between what a human being is and what a human being does.”

This is from a man who in 1960 defied the authorities by refusing to vacate the Whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro. Over half a century later, he became a leader in the organization that filed the amicus brief with the Supreme Court in support of the White bakery owner’s right to snub a Black couple looking to buy a wedding cake.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

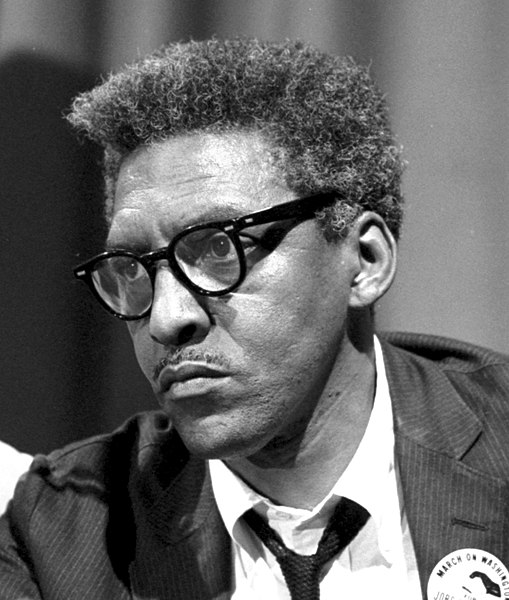

The ambivalence toward gays among African Americans has deep roots. When Martin Luther King Jr. was tipped off about Bayard Rustin’s openly gay lifestyle, he distanced himself from the fellow civil rights leader and kept him at bay for several years. As did Roy Wilkins who prevailed on his colleagues at NAACP to render Rustin invisible in the 1963 March on Washington.

In his autobiography, W. E. B. Du Bois gave a moving testimony about his own struggle with the issue: “A young man [Augustus Granville Dill], long my disciple and student, then my co-helper and successor to part of my work, was suddenly arrested for molesting men in public places. I had before that time no conception of homosexuality. I had never understood the tragedy of Oscar Wilde. I dismissed my co-worker forthwith, and spent heavy days regretting my act.”

We should be careful to distinguish the deficit of civic imagination from the surfeit of bigotry driven by a hatred toward people on account of their membership in a supposedly inferior class. Yet freedom fighters are known to harbor strong prejudices, juxtapose their political identities to those of lesser tribes, and insist on the superiority of their constitutional claims.

Susan B. Anthony, a women’s right pioneer and a committed abolitionist, turned against her longtime ally Frederick Douglas when he backed the 15th Amendment enfranchising Black men before White women. Speaking at the 1869 American Equal Rights Association’s meeting, Ms. Anthony declared: “The old anti-slavery school say women must stand back and wait until the negroes shall be recognized. But we say, if you will not give the whole loaf of suffrage to the entire people give it to the most intelligent first. If intelligence, justice, and morality are to have precedence in the Government, let the question of woman be brought up first and that of the negro last.”

A few decades later, Alice Pole expressed a similar sentiment when she bristled at the prospect of Black and White suffragists marching side by side in the 1913 Women Suffrage Parade: “As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.”

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s bias was blunter still. An ardent feminist and the acclaimed author of Women and Economics, she inveighed against immigrants inundating American cities. Her attitude toward Jews was unabashedly racist, as she alleged in her autobiography that “one third of the inhabitants of New York now are Jews” and predicted “the rapidly descending extinction of our nation, superseded by other nations who will soon completely outnumber us.”

As these examples attest, being marginalized is no guarantee that one will be sensitive to the needs of minorities further down the totem pole, or that exclusionary practices would not infect the victorious liberation movement. The tension brewing within the LGBTQ community is the latest manifestation of this pattern.

Midway through the 1990s, transgender activists began to join forces with the organizations advocating for the rights of gay, lesbians, and bisexual people on the assumption that their shared interests and the political clout of the LGB community would help advance the trans agenda. Now the alliance shows strain, as the transgender and transexual activists discover that their priorities aren’t always aligned with the coalition partners.

Several activists writing for the inaugural issue of Transgender Quarterly sounded alarm about the fact that “more and more gender-normative, economically and racially privileged, coupled, and metropolitan gays and lesbians are crossing into the mainstream” (Heather Love). Ana Cristina Marques recently published a paper where she spotted the “radical trans-exclusionary feminist attacks on transgender people” which, her research showed, could make transgender people feel unwelcome in the spaces patronized by gays and lesbians.

The issues dividing the advocates for these group are complex, the most salient ones being the traditional gender binary and the embodiment challenges stemming from sex-reassignment, neither of which riles gay and lesbians the way they can disrupt the lives of transgender folk. But these issues are serious enough for students of gender and trans rights advocates like Susan Stryker and Zein Muribo to contend that “LGBT privileges the expression of sexual identity over gender identity,” that “listing ‘T’ with ‘LGB’ – and at the end, no less – locates transgender as an orientation,” and that “although the inclusion of transgender alongside lesbian, gay, and bisexual opened up new political alliances across these groups, it also closed off possibilities for coalitions with different political groups – such as activists fighting for immigrant rights who face concerns over documentation that are similar to those of transgender people.”

I will not go into the nascent friction between the transgender and queer advocates over who better represents the marginalized people, the friction that threatens to further weaken the LGBTQ coalition. The point is that we need to rethink what we mean by “identity” and “alliance” if we want to fend off the more destructive implications of identity politics.

Identity is not a fixed quality, a visible attribute manifesting itself in predictable fashion across space and time. It is an ongoing accomplishment, a project we undertake to realign our actions, feelings, and words in response to competing possibilities for enselfment. Contrary to popular belief, self-identity has more to do with what one does than with what one is. It is always tested by our rival commitments which are bound to clash on occasion and muddle our allegiances.

The competing demands on our civic imagination remind us that alliances we form are not sacrosanct, that cliques, groups, and classes we belong to are not entities safeguarded by border patrols but emergent social fields whose gravitational pull is bound to breed ambivalence – a mark of emotional intelligence pervading moral life.

Nor should the exercise of civic imagination be limited to human targets. What about animal rights, living creatures subject to vivisection for the benefit of humankind? Maybe it’s time to phase out Premarin, the estrogen-based drug (used by transgender people among others) which is extracted from the urine of mares forcibly impregnated and kept for months in cramped stalls. And is it too fanciful to extend civic imagination to the planet earth whose depth we plunder and whose habitats we methodically destroy?

So, before we cast a jaundiced eye at the civil rights fighters of yore who were not as woke as we are, we should check our own privileges and reach out to those who fair worse than we are.

Bayard Rustin lived as an openly gay man long before society acknowledged his right to do so. The year he died, in1987, he stated: “Twenty-five, 30 years ago, the barometer of human rights in the United States were black people. That is no longer true. The barometer for judging the character of people in regard to human rights is now those who consider themselves gay, homosexual, lesbian.”

Not everybody is blessed with the clear-sightedness and audacity of Bayard Rustin. It took years for Barack Obama to evolve on the issue of marriage equality before he summoned his valor and got onboard. There is room for all of us to evolve. And keep evolving, as we practice civic imagination and reach across political divides.

Click Here to make a tax-deductible contribution.

Barack Obama “summoned his valor” to promote marriage equality?

No, not quite: Barack Obama responded to threats by David Geffen and other gay Democratic donors to stop contributing money to the Party. The word “valor’ and the name Barack Obama do not belong together under virtually any circumstances; instead of “valor,” try “brand consistency.” It’s far more appropriate.

Albert Memmi extensively documented how the North African decolonial movements of the 20th century turned into movements that viciously hounded the Jews out of their countries, then hated them for fleeing to Israel. He maintained that after a certain point, the “decolonized” ruling classes bore responsibility for the continued misfortune of their “decolonized” masses. It’s very sad.