Herbert J. Levine, Words for Blessing the World: Poems in Hebrew and English (Ben Yehuda press, 2017).

Yaakov Moshe, and Jay Michaelson. Is: Heretical Jewish Poems and Blessings (Ben Yehuda press, 2017).

When Bob Dylan first sang that: “Inside the museums/Infinity goes up on trial”, his prophetic impulse with “Visions of Johana” (1966) could not have been stronger. The “museums” of American Judaism are the synagogues that resemble a dybbuk that haunts us, sticking here and there, but ultimately feeling more like a plague to be exorcised for most American Jews. Even more to the point, when awarded the Nobel for Literature this past June, Dylan took as seriously as an Americana Jewish trickster could, the question “exactly how [are] my songs related to literature?” For Dylan the project of translation between the worlds of lyrics to literature is ultimately less difficult than one might expect—he doth protest too much!

Dylan’s songbook feels like a solitary soundtrack to this rallying against every institutional expression of religion within the metaphysics of secularism that typifies the American landscape of the wanderer. Yet as John L. Modern argues in his Secularism in Antebellum America (2015): “lonely missives to God [are] constituting a mediasphere.” When spirituality becomes a “mode of haunting and a means of disenchantment” there is a deeper inspiration that fuels the imagination at work here. The current mediasphere that emerges along this lonely landscape is one full of wayfarers and god-fearers. There must be a gossamer thread of metaphysics that is woven through this fabric of secularism in America. Even though secular modernity in America has been highly imprinted by Protestant practices and its particular metaphysical commitments in which “the truly religious and the truly secular were inscribed, seamlessly and simultaneously, with the mark of the real.” That such an experience of reality so tightly interweaves the religious and the secular means that living in America has a religious feeling while living in a secular age. Given that this kind of reality is neither “totalizing nor utterly determinative”, Dylan’s songbook thus picks up on a strange lightness of being, as captured in “Man in the Long Black Coat” (1989) whereby “people don’t live or die, people just float.”

However, recently I have been asking myself an inverted version of this question in reading two remarkable collections of poetry by Herbert J. Levine and Yaakov Moshe—namely, how does this devotional poetry relate to, and even sing, like prayer in a post-secular context? Not necessarily the fairest of questions, given that while all strong poetry may return to its source in song, it does not mean that every poem is intended or even suitable for prayer. So perhaps we may need to limit the question as to whether these poems are simply prayerful. Regardless, it is truly remarkable to see the response of these two poets to Shaul Magid’s call in Tikkun (Winter 2015) for “forms of Jewish worship to embody Schacter-Shalom’s paradigm-changing approach to Jewish theology.” While still abiding on this mortal coil, Reb Zalman admitted that his desire to do paradigm-shift liturgy was never realized during his lifetime, but that that time was-a-comin’! Reb Zalman was one of the pioneering theologians to attempt translating James Lovelock’s Gaia consciousness (1974) into a Jewish cosmotheism. What Lovelock’s Gaian hypothesis envisions is that living matter on the earth collectively defines and regulates the material conditions necessary for the continuance of life. The planet, or rather the biosphere, is thus likened to a vast self-regulating organism.

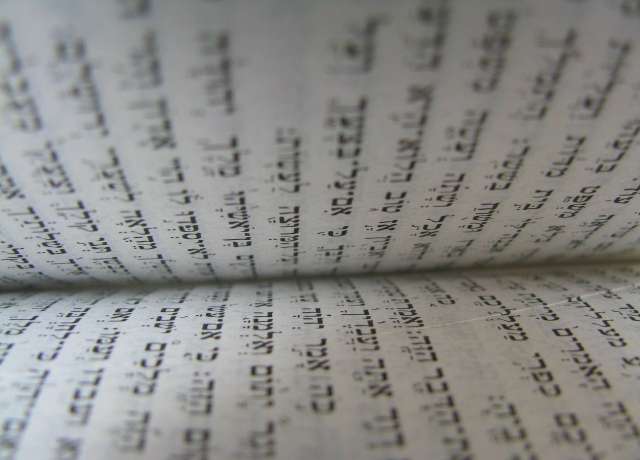

Such a vast self-regulating organism needs its own poetic response and Levine’s Words for Blessing the World: Poems in Hebrew and English is an unabashed response to that call (53-55), while Michaelson’s Is: Heretical Jewish Poems and Blessings feels more like a concealed response to that impulse (93-95). In what follows, I will briefly analyze each collection of poetry, with an eye to extrapolating the theological implications for next paradigm Judaism(s) and the possibility of offering such prayerful poems.

From the vantage point of “Inside the museums”, Michaelson’s Is: Heretical Jewish Poems and Blessings can be situated squarely as rebelling as part of an intoxicated band of godlovers, primarily those SBNR (“Spiritual-But-Not-Religious”) seekers or those “believers without boundaries” once known as “heretics” (94). From the vantage point of “Infinity goes up on trial”, Levine’s Words for Blessing the World exemplifies a heeding of his master’s call to envision a Gaian community that sees humans as the embodiment of the cosmos becoming self-conscious and thus responsible for the future of that evolution. That both poets present these prayerful poems as offerings at this urgent moment in time evinces a greater zeitgeist unfolding.

For poets to confess their lineage is likely the only heresy that remains today, and even when precursors are cited, too often readers today have little clue as to who these great poets might have been and why they mattered so. As I have argued elsewhere, strong Hebrew poets are prophets for future Jewish thinking and so it is worthwhile considering these two unique poetic offerings. Michaelson (aka Yaakov Moshe) doth protest too much in claiming “I’m not sure if I’m qualified to contradict myself in the style of Walt Whitman, that great queer avatar of spirit and body unchained.” (94) Only Harold Bloom would still argue today that there is only one Walt Whitman (as I learned in arguing with him over whether the Israeli poet, Haya Esther, could be read as a Hebrew Walt Whitman). All humility aside, great poets aspire to great heights, and Michaelson is doing more than wearing his Hebrew nom du plume of Yaakov Moshe as drag, but embodies it in full poetic regalia, channeling precisely a Hebrew lineage (in the sense of the Canaanite poets after Yonatan Ratosh, rather than any Jewish) version of that “great queer avatar of spirit and body unchained” in his poetry collection. Putting it all on the line in one word— “Is” — Michaelson’s poetry is attempting “to gesture at whatever numinous mystery sits inside Robert Frost’s circle, or at the happiness that does not depend on conditions—that quiet sense of spaciousness that emerges in what Virginia Woolf described as bare ‘moments of being.’ (Or Being, if you insist).” (95). Such desire to touch the heart of Being is the poet’s valiant attempt to translate that very elusive event of existence—not at all unique to the American religious poet precursors he deftly cites—but resonates within what the ancient Hebrews called HaVaYa as the basis of the YHVH Tetragram. Michaelson is still willing to schlep the traces of transcendence forward by naming it as “Is”. Whether this contemplative insight comes from countless hours of silent retreat or delving into kabbalah, Michaelson has mined a gem here.

By contrast, Levine retells wisdom from his father about the Potlatch ceremony of mutual gift-giving between tribes: “If we did not carry on, our hearts would break” and glosses it through his own poetic vision: “If I carry on in this way, my mind will break”—“this way” of course referring to such traces of transcendence. Levine instead carries forward the gift that Reb Zalman gave him with the challenge of translating this blessing of Gaian consciousness as barukh ata olam (“O blessed world, you”, 6/7). This is at once creative and strange, but is it still heretical? Some traces of such prayerful heresy abide in forgotten Sabbetean siddurim that point in the other direction, namely, away from any concept of transcendence with an invitation to immersion in the limitless sea of the divine as barukh ata Eyn Sof (“Blessed Are You, Without End”).

The language of address in prayer for spiritual progressives can be perplexing if not plaguing. Recall pioneering American poets like Marcia Falk, in her The Book of Blessings : new Jewish prayers for daily life, the Sabbath, and the new moon festival = Sēfer hab-berâkôt (1999) and how there she dared to remove all patriarchal trappings of the rabbinic formulation of “the canonical combination of tetragram and sovereignty” (referred to as shem u’malkuth), replacing it all with “Let us all bless the Source of All Life” [Nevareikh makor hayyim]. This seems to have been accepted into Reform siddurim and some Renewal circles without a book ever being burned (a fate that Mordecai Kaplan’s Reconstructionist siddur could not transcend at the hands of his Conservadox colleagues!) Falk understood the need for prayerful poetry and thus also included her English translations that make up the bulk of The Book of Blessings poetic additions, primarily Yiddish poetry, along with the first fruits of her larger translation project of Zelda Schneerson Mishkovsky, The Spectacular Difference: Selected Poems (2004). Early on, Falk was concerned with this project of renewing liturgy in a non-patriarchal modality, with essays like, “Notes on composing new blessing: toward a Feminist-Jewish reconstruction of prayer.” (1987). Falk was not alone in this regard, especially important in moving forward the theological basis of the discussion were feminist theologians whose pioneering works are still consulted today, like Rachel Adler’s Engendering Judaism : an inclusive theology and ethics (1998) and Judith Plaskow’s Standing again at Sinai : Judaism from a feminist perspective (1991), both of which are thoroughly embraced by Reform Judaism.

What Levine beckons in his poetry is a radical shift away from the transcendent to the immanent, from the supernatural to natural—a move that Zelda’s poetry desired but could never be limited by as her wild cosmic abandon carried her away. There is a certain analytical sobriety to Levine’s poetry project, while laudable, sometimes feels more like the insights one might glean from great lesson in Hebrew grammar rather than the rapture that comes from being ravished by poetry. Although one would have thought that the final chapter in that lost history of American Hebrew poetry was written by the late Alan Mintz with his now classic, Sanctuary in the Wilderness: A Critical Introduction to American Hebrew poetry (2012), now that an American poet like Levine is writing in an exquisite Hebrew must be commended as a remarkable accomplishment. Only Tzemah Yoreh seems to be attempting this experiment with his Humanist blessings and siddurim. Yoreh confesses not to be praying to Gaia, rather: “By praying we validate those communal aspirations and give ourselves strength to continue” which resonates with his project of finding a rigorous and authentic Jewish humanist prayer. Whether it is the community or the world, the reflex in the cases of both Levine and Yoreh is to simply substitute one concept for another. If a transcendent, theistic, patriarchal deity is no longer tenable, or as Levine puts it “an improbable God” (38), then does merely substituting and praying work? Does such prayer have any meaning? If prayer is that yearning to take leave of what German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber once called our “I-It” mundane relationships that objectify every person, place and thing around us to reach out to an “I-Thou” in conversation, then where is the conversation happening here in this prayerful poetry? With the larger community? With the world? Perhaps. But, if as Levine astutely reminds us, “in Hebrew, to pray is a reflexive verb” (8), then maybe he is justified in claiming “You need only yourself— the ‘I’ that fears, makes people made, and complains,/and the ‘I’ that includes/all the ‘I’s in the world,/and asks that you have compassion on yourself/and on them all.” (8)

Levine should be commended for attempting the impossible—to write the prayer of Baruch de Spinoza (d. 1677)—the heretical philosopher whose first name was a formulaic theistic blessing he utterly rejected. To carry forward the pristine naturalist philosophy of this Jewish heretic—and to a lesser degree the reconstructionist theology of Mordecai Kaplan and the neo-hasidism of Art Green—is to accept Spinoza’s original supposition that every person is ultimately guided by fear and hope, so that all our behaviors are calculable in relation to what we desire. The existence of being is all we can call out to, nothing more. This humanist calculus means that any act of prayer, worship, offering, sacrifice and other related ritual trappings of popular religion are woefully insufficient, if not utterly embarrassing. Spinoza challenged his Jewish community in Amsterdam as well as humans across the globe to get control of those pesky and fleeting emotions as well as all those superstitions that constituted the theistic Judaism he could no longer accept. Lest we forget, Spinoza did try his best to salvage any useful fragments from the reliquary of Judaism, as he admits in his scandalous, Theological-Political Treatise: “Immense efforts have been made to invest religion, true or false, with such pomp and ceremony that it can sustain any shock and constantly evoke the deepest reverence in all its worshippers”. (Theological-Political Treatise, Preface, G III.6–7/S 2–3). But the lack of rational foundations, coupled with a mistaken “respect for ecclesiastics” involving mysteries but no true worship of the divine totality left Baruch as empty as so many seekers feel today. The jury is out whether today’s seeker searching for prayerful poetry to worship the ultimate mystery will be left empty or full. It may then come down to personal positioning, which is highly subjective as to whether prayer is indeed an art. If it works for you aesthetically, why not pray it?

The abiding concern that keeps me personally from delving deeper into this sea of this prayerful poetry of Levine is when it comes to Yehudah Amichai (d. 2000). Clearly, every strong poem Levine writes in Hebrew is an ode, imitation and resonance of Amichai. If prayer is also about connectivity, then Levine is deeply connected in these poetic offerings to both the late, great Hebrew poet with “To Yehuda Amichai” (40/41) as well as to the American pragmatist prophet of Renewal, Reb Zalman Schacter-Shalomi with “I Make a Covenant of Peace with You” (44/45). Levine has managed to worship the world as a self-contained immanent divine source and two figures that make his poetic-prophetic vision come alive, and in so doing, he has realized the ultimate humanist albeit heretical prayer. It is no small feat to make a covenant of peace with Reb Zalman nor to say Kaddish addressed directly to Amichai “May your name be made great and revered” (40/41). Yet we underestimate the power of heresy and the anxiety of its influence even today in this post-secular American Jewish landscape. Lest we succumb to the plague of American Jewish short-term memory, let us not forget that there was no shortage of Sabbatean siddurim that ingeniously filled the negative and generative space of the Tehiru in that delicious moment of divine self-withdrawal necessary to make creation of God and the world possible, with the incarnate presence of AMIR”AH, aka Sabbetai Zvi (d. 1676). Why that was heresy then, but remains immune to heresy as the preferred sect of American hasidism when the late Lubavitcher Rebbe’s name is inserted into the Kaddish in some meshikhitin shteibelach, remains a mystery. It is precisely here that Yoreh’s kavvanah preceding the Shema is instructive: “With the reading of this passage, I wish to show my respect for my foremothers and forefathers, who worshipped God with sacrifice and hardship. And though I can offer no song or prayer to an anthropomorphic god (or to any god), as it says: “Be careful lest you make yourselves an idol or any image of a male or female”, their traditions are engraved upon the tablet of my heart.” Idolatry is always a near and present danger when the divine totality is elided from the triad that Franz Rosenzweig so beautifully explicated as the foundational triads of his reading of the Star of David as the Star of Redemption, being God-World-Human intersecting with Creation-Revelation-Redemption. Remove one of the vertices and the dynamic interrelationship ceases, and the creative tension of the dialectics collapses into imbalanced essences.

Like Yoreh, Levine’s flourish is found in his mastery of Hebrew. So, while Levine amazed me with poetry that speaks of “sleep apnea” in Hebrew as dom haneshimah b’shayna (23), I was disappointed to read “fantasies” translated as a limpid loan word (39). The strength of Levine’s prayerful poetry comes in a flash, in writing those “unwritten white spaces” of forgotten scriptures especially when he embodies the other, like Ishmael (28/29) and Esau (28/29) as well as countless feminine voices, otherwise absent from Scripture in his own poetic midrash of sorts. But Levine’s real genius shines through when he says the unsaid that bedeviled Amichai all his life: “The Palestinians commemorate their tragic Naqba, /a holy day of remembering and mourning the loss/of their nation. When the day comes that they celebrate the beginning of their state, I suggest they also celebrate/a Palestinian Purim, with costumed, masks and hashish/ (the Muslims won’t be drinking alcohol)”. (22/23) Only the pathos of the poet could make such a spiritual suggestion so that in the end his heresy shines like a diamond: “when they’ll wipe out the name of Israel/once a year, and they’ll say what Jews say/on Hanukah, Passover and Purim: They tried to kill us/but they failed, so let’s eat rich food/and tell funny stories/to keep living well and not fall/to the bottom of memory’s black hole/of tears and shame and fury.” (24/25). This poetic insight of Levine is the greatest surprise blessing of the book!

Michaelson’s poetic flourish comes in his willingness to still dawn to god-language of hasidic masters in crying out Ribbono Shel Olam (“Master of the Universe”) while cutting loose the ties that bind, namely, any remaining boundaries that would claim to contain their ecstatic yearnings inside the walls of the shteibl, or any house of prayer with walls. While never as explicit as Levine, Michaelson does nod to Reb Zalman when he poetically captures the master’s renowned oral adage: “I don’t care about the God you don’t believe in/I want to know what prompts wonder in you” (38). But the poet reaches new heights as he extends this adage with a recurring sip of Rumi’s quatrains: “I have more in common with the atheist who dances/Than with the so-called pious, /asleep.” Michaelson is playful in his panentheistic flourishes, echoing Levine, when he writes: “So if you are sometimes in love with the world”, but never succumbing to Levine’s full-fledged devotion to the world as Gaia. Rather Michaelson settles for being present to the pragmatism of: “now in wiser moments/i pray only that I will remain/aware/of this” (39). The deeper grooves of an ecstatic contemplative come through in marvelous moments like these and allow the Jewish seeker to finally begin to let go of Coleman Barks’ Americanized interpretive adaptations of Turkish Sufi poet, Rumi and embrace that great Jewish queer avatar of spirit and body unchained.

Ultimately, we still have time to respond to Magid’s call, but it is up to each of us to leaf through some of the most aspiring and inspiring American Jewish poets, like Levine and Michaelson, who are not only writing a prayerful poetry that may be our future liturgies, but now is the time to pray their poetry. If not now, then when and moreover, how will each of us as seekers find a way to be more than singing peddlers like in “Visions of Johanna” and ever be able to respond with anything more than “skeleton keys” to ensure the song still can sing itself? Dylan directed his prayerful poem to that “caring countess”, just as these prayerful poets direct their prayers to the biosphere as a vast self-regulating organism as the “empty cage now corrodes” and to the divine totality as the love supreme as “as my conscience explodes.” Even if we are still left wondering whether we can really achieve a lasting meaning through these prayerful poems, these poets leave us with the hope that their poetry will intercede on behalf of our skepticism to: “Name me someone that’s not a parasite and I’ll go out and say a prayer for him”?

__

Aubrey L. Glazer, PhD, (University of Toronto, 2005) currently serves as senior rabbi of Montreal’s Congregation Shaare Zion, and has served as senior rabbi of Congregation Beth Sholom, San Francisco (2014-2018) as well as Jewish Community Center of Harrison, New York (2005-2014). As a graduate of the Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Aubrey has co-lead Jewish meditation retreats at Makor Or with Zoketsu Norman Fischer as well as teaching Zohar in the Philosophy Circle of Lehrhaus under the direction of Daniel Matt. Aubrey’s recent publications in contemporary philosophy and spirituality include: Mystical Vertigo (Academic Studies Press, 2013); Tangle of Matter & Ghost: Leonard Cohen’s Post-Secular Songbook of Mysticism(s) Jewish & Beyond (Academic Studies Press, 2017) and God Knows Everything is Broken: Bob Dylan’s Great (Gnostic) Americana Mystical Songbook (forthcoming). Aubrey is director of Panui: an open, contemplative space for researching and development in modern and contemporary Jewish mysticism in a dynamic and authentic way to build conscious, compassionate community.