In 1945, philosopher Karl Popper set the standard for validating liberals’ intolerance of conservatives’ prejudices. It’s now common to argue, as he did, that intolerance of intolerance is necessary. Supposedly without it, the horribly intolerant would dominate society. To liberals, strident opposition to intolerance seems like a damn that contains hostile, demeaning words and behavior. Moreover, the Left’s intolerance of the Right’s prejudicial practices is much less damaging than the Right’s often hateful words and sometimes murderous behavior against their “inferiors.” And the Left’s intolerance of intolerance is well intentioned. It’s an attempt to end the destructive prejudice that abounds, whereas obviously egregious intolerance has only a negative aim and effect. However, these arguments for the validity of intolerance of intolerance fail to take account the unintended effect of so-called Political Correctness on the Right.

Popper’s idea holds sway in 2018 among self-avowed defenders of Political Correctness, including Eddie Glaude, Jr., Professor of Religion and African American Studies at Princeton University. On the talk show, Real Time With Bill Maher, Glaude said, “At the heart of Political Correctness is this reality, that this country is no longer a white nation in the vein of Old Europe. White straight men can’t walk around saying whatever the hell is on their minds. Period.” Rebecca Traister immediately chimed in, saying, “That’s right. That’s right.” She is a writer-at-large forNew York Magazine and author of Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger.

It’s not obvious to these advocates of intolerance of intolerance that their intolerant words are damaging to their political self-interests. But intensely anti-Trump conservatives are trying to help the Left come to that realization. In Atlantic Monthly, McKay Coppins quoted Russell Moore, a leader of the Southern Baptist Convention, in the service of helping the liberals to reconsider their intolerance of the intolerant. McKay quoted Moore as saying, “It was only a matter of time before cultural elites’ scornful attitudes would help drive Christians into the arms of a strongman like Trump. I think there needs to be a deep reflection on the Left about how they helped make this happen.” Note that Moore is intensely anti-Trump. He truly is trying to help liberals take seriously that their intolerance, however well intentioned, is having a terrible effect.

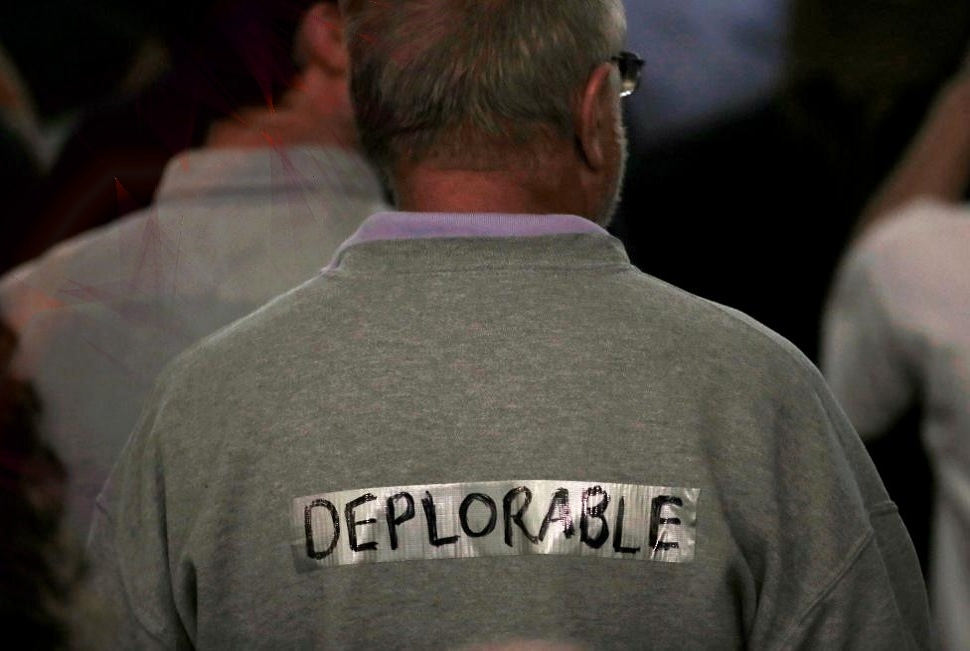

Hillary Clinton’s egregious “deplorables” gaffe did seem to drive some moderate conservatives toward Trump, despite how disgusted they were with him. But to the average conservative, her blatant degradation of the Far Right is only one of many illustrations of the scorn the Right endures.

A Trump supporter subtly hinted at this widespread degradation of the Right by the Left. Dale Berry politely captured what may be the sentiment of many people like him. He is not a member of Trump’s organization, and Berry is a mild-mannered guy. He said, “On a general level, one of the biggest problems we have is this PC culture where people are afraid to say things.” They’re afraid to say their views for fear they will be demeaned in public.

Glaude might object, arguing that he’s only trying to correct corrosive views, not put people down. But his demeaning tone is unmistakable in the quote above: “White straight men can’t walk around saying whatever the hell is on their minds.” But tone is the least of the problems inherent in the Left’s criticisms of the Right.

Liberals tend to practice blatant name-calling without realizing that they are. The Left tends to think of the word, “racist,” as only a factual description, as in a dictionary definition of “racist”—”a person who shows or feels discrimination or prejudice against people of other races, or who believes that a particular race is superior to another.” But the degrading connotations of “racist” are deeply felt by people on the Right. “Racist” does inevitably imply that the object of this epithet is stupid, mean-spirited, and much worse. Perhaps the most unmistakable and ironic implication of calling someone a racist, one that is felt most keenly by the Right, is that the so-called racist is inferior.

“Homophobe,” “sexist,” “misogynist,” and many more descriptors are painfully familiar to conservatives. Steve Deace, a Christian radio talk show host, powerfully expressed the reaction of the Right to this name-calling. He said,

As long as Democrats remain the party of infanticide and ‘bake the cake, bigot,’ there is literally nothing Trump could do to alienate a majority of his evangelical support. [Trump is seen] as the last remaining barrier between them and the Left using the full coercive power of government against their beliefs.

The phrase, “bake the cake, bigot,” is the Right’s attempt to mock the Left for forcing baker, Jack Phillips, to put gay-appropriate decorations on a wedding cake a gay couple asked him to create. Phillips was forced to close his bakery for months and then endure a lengthy judicial process that culminated at the Supreme Court.

Perhaps, as Deace implies, so-called “infanticide” is by itself a deal-breaker for conservatives who otherwise might vote for a moderate/liberal. But research shows that this supposition isn’t true enough to make all the difference in an election. Consider that the Right is not as unanimous in its opposition to abortion as many people may believe. A Pew Research Center study found that 30 percent of evangelical Christians do not advocate outlawing abortion, and some proportion of the remaining 70 percent are not absolutist. They allow abortions in some circumstances. The combination of non-absolutists and conservatives who don’t want a law against abortion does seem significant. But as Moore explained, the essentially hostile, rejecting implication of the Left’s degrading speech, is significant.

An alternative method for relieving people of their prejudices is emerging. It’s empathetic insight. Here’s an example that many writers have noted and deserves a broader hearing. A most basic understanding of prejudiced people is that they don’t choose to believe that people unlike them are inferior. People do not choose to be prejudiced. Their opinions are formed in their homes and communities. Their commitment to prejudicial beliefs is in many cases forced on them, not chosen. And such people are so difficult to engage in reasonable conversation, mostly because they sense that they must fight back against the degradation and confusion of being called inferior for thinking that some people are inferior. They’re fighting more against the degradation than for their views.

Of course, there are many psychological theories to explain why any person believes that someone else is inferior. “We put down people we don’t understand, because we’re afraid of their differentness,” is one of the most prominent theories. But this and many other theories may miss the point that the doggedness with which a person stays committed to a prejudicial view is at least significantly explained as a reaction against the degradation, “You’re a racist,” meaning, “You’re inferior!”

An alternative method for trying to correct people’s harmful views is to empathize with such people, to try to understand why they believe as they do. Imagine sitting in a Southern café and overhearing the person next to you at the counter, saying, “All them Mexicans just want to take over our jobs and use up our tax dollars for all the damn services they’re getting from the government.” Imagine further, trying to crawl inside that person’s position, asking questions or even provisionally agreeing, as in, “It does seem that they’re getting a lot of services, and that can piss people off.” This tack can and often has led to a much less defensive and productive conversation.

Imagine further a national liberal leader, someone of stature of Hillary Clinton, apologizing for her hostile, demeaning attacks against the Far Right and otherwise trying to engage the Right in a reconciling conversation. She might say,

Since the last election, I’ve had to face the fact that I violated the most important principle of my own religion. I was raised and continue to be a member of the United Methodist Church, and when I totally demeaned half of Trump’s supporters, I went against the most profound teachings of the Church. During the campaign against Trump, I said, “You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right? The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic—you name it.”

These and other hateful, degrading remarks violated the most profound law in the Bible, the law of love that teaches us to love our enemies. I’ve fallen far, far short of obeying that law. I hurt and enraged many people and live with intense shame and guilt for having done that.

I can’t take back what I said, but I can, starting now, try to set a new standard for political discourse that is based on my deepest values that I’ve touted but haven’t lived up to. Respect, whether mutual or not, has got to be part of the centerpiece of our attempts to persuade each other. And as I’ve already said but didn’t at all consistently practice, empathy—fully standing in the shoes of people with who we disagree—must become our means for achieving mutual respect and, ultimately, the reconciliation of the people.

Clinton’s self-contradictory commitment to at once empathizing with our foreign enemies and at the same time trashing our own people during the most important campaign of her life, makes the point that empathetic understanding is difficult to consistently apply. Who can consistently empathize even with one’s loved onse But although no one can be consistently empathetic, empathetic insight is emerging and perhaps is a method for solving our most difficult problems whose time has come. And although most people don’t realize that empathy is at the core of liberal’s humanitarian values, it is. We know that this method is at the core when we look at progressives’ history and see the record of the Left’s empathy for suffering, oppressed people the Right tends to moralize against. No great psychological/ideological upheaval is needed. We need only expand the boundaries of the kinds of people with whom we can empathize, not embark on a totally unfamiliar course.

__

John McFadden is an ordained Presbyterian Minister and CA State Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist. Parts of this article are excerpted from his published book, A Christian’s Intervention for Trump: The Dawn of an Empathy-Based Morality.