I

In the last years of the nineteenth century, two adolescent great powers — the United States of America and the recently founded collection of states called the German empire — stepped onto the world stage, flexing their muscles and arming for war. Both nations quickly built up their fleets. The German Empire began construction of four battleships in 1890, all of which were launched by 1894. The United States began building armored cruisers in 1891 and, by 1898, had three, one of which, the Maine, blew up on February 15, 1898, while anchored in Havana harbor. The explosion provided a pretext for the U.S. to declare war on Spain and, subsequently, to invade Cuba, the closest of Spain’s New World colonies.

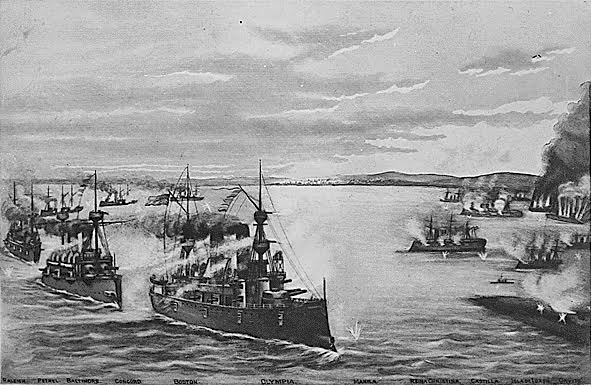

On April 25, 1898, two months after the sinking of the Maine, President William McKinley declared war on Spain and ordered Commodore George Dewey, in command of the seven-warship U.S. Asiatic Squadron, to “capture or destroy” the Spanish Pacific fleet in Manila Bay. The mission was quickly accomplished: begun at dawn, it was over by noon. “By a morning’s battle,” Dewey subsequently observed, “we had secured a base in the Far East … when the parceling out of China among the European powers seemed imminent.”

Having destroyed Spain’s warships, Dewey established a blockade sealing off Manila Bay’s sea approaches. On June 12, 1898, the German East Asia Squadron, consisting of five warships and two auxiliaries, steamed into the bay, following the emperor’s orders to protect German interests and to investigate the possibility of acquiring a base in the sprawling archipelago. Disagreements over the Americans’ right to board German ships tested Dewey’s patience to the point where he shouted at one of the German commanders, “Tell your admiral if he wants war I am ready.” The Germans backed off. Later, Dewey confided to a correspondent, “Our next war will be with Germany.”

That was to come. In the meantime, in 1900 soldiers of both nations – part of an eight-nation alliance — found themselves united in a battle to protect the business interests and legations of European nations in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion, a name alluding to the martial arts practiced by peasants driven to the edge of poverty and determined to purify China of its contamination by foreign influences. From June 20 to August 14, the Chinese army and Boxer irregulars besieged the Legation Quarter, which harbored foreign civilians, soldiers, marines, and sailors, as well as some 3,000 Chinese Christians. The Quarter was ringed by the so-called Tartar Wall, forty-five feet tall and forty feet wide. Defense of two key sections of the wall was divided between German and American troops. On June 30, when the Germans were forced to pull back and while Marine Captain Newt Hall was rounding up reinforcements, Private Daniel Daly, armed only with a bolt-action rifle, defended the sector against hundreds of attackers, an action for which he was duly awarded the Medal of Honor. Daly subsequently became famous for urging his company to charge German positions during the 1918 Battle of Belleau Wood by shouting, “For Christ’s sake, men: come on! Do you want to live forever?”

Within less than a score of years the two nations that, in 1900, in common cause had fought, looted, and killed Boxers and civilians alike, faced each other as foes.

II

Both the German and American soldiers came to Asia with their own socially acceptable racial prejudices – anti-Semitism being a common factor, as well as anti-people of any color than their own – which were broadened and deepened by their experience in the East. Kaiser Wilhelm had set the virulent tone in his July 27, 1900, address to the troops before their departure for China. After urging the men to behave like Christians, he went on to contradict himself: “Prisoners will not be taken…. You should give the name of Germany such cause to be remembered in China that for a thousand years no Chinaman…will ever dare to look cross-eyed at a German again.”

In August, an armistice was signed between Spain and the United States and in December 1900 the Spanish-American war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris, which granted Puerto Rico and Guam to the U.S., as well as the Philippines – a deal that infuriated the Filipino insurgents who, under Emilio Aguinaldo, with American encouragement, had cornered and all but conquered the Spanish forces by the time the Americans arrived on the scene. (Andrew Carnegie, who strongly opposed America’s refusal to grant independence to the Filipinos, offered to donate $20 million to the people so they could buy it back.)

So now a new war with a new name broke out. The Philippine-American War, which began on February 4, 1899, ended on July 2, 1902, six weeks after Aguinaldo urged his followers to lay down their weapons, saying, “Let the stream of blood cease to flow; let there be an end to tears and desolation.” Refusal to believe that people of color could rule themselves, together with a reluctance to pass up the chance to acquire a strategically located piece of property, resulted in turning America’s native allies into enemies. Filipinos became goo-goos, niggers, or President McKinley’s term, “the little folks.” In Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the Philippines, David Haward Bain cites soldiers’ letters home, with one writing: “our fighting blood was up and we all wanted to kill ‘niggers’…. This shooting human beings beats rabbit hunting all to pieces.” An estimated 1,500 Americans were killed in action during the conflict; nearly twice that number died of disease. For the Filipinos the cost was far greater, with an estimated 20,000 combatants killed and more than 200,000 civilians dying of violence, famine, and disease.

Germany, meanwhile, had been scrambling to catch up with older European heavyweights that had long since acquired colonies. In the Pacific, the German East Asia Fleet steamed up to Guam with high hopes of seizing that small but strategically important prize only to find that the Spanish governor had already surrendered to an American warship on its way to the Philippines. In Africa, Germany had acquired Togoland and a slice of the Cameroons in 1884, as well as a thin coastal strip of land in South West Africa (now Namibia) which a German entrepreneur had bought from a native chief.

In 1885, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck sent a fifty-six-year-old court assessor named Dr. Heinrich Göring to assess the situation in this new territory said to be rich in minerals, including gold, and to extend German authority over the region. The portly assessor, who had fathered five children and had recently gotten a young woman pregnant and who, in 1893, would sire a son named Hermann, was presumably eager to accept a foreign assignment.

III

By the time Göring set out for South West Africa in the summer of 1885, he could boast of an imposing new title: Reichskommissar, or imperial commissioner. This was a consequence of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, organized by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, whose purpose was to negotiate borders of African territories claimed as colonies by thirteen European nations, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, and to spell out the conditions that would legitimize a nation’s claim to a colony: a treaty with local leaders, a central administration, a police force, and the flying of the nation’s flag. Article 6 of the General Act declared: “All the Powers exercising sovereign rights or influence in the aforesaid territories bind themselves to watch over the preservation of the native tribes.” (Two-hundred and forty-five Black Americans were lynched during the time span of conference.)

On arriving at a small Southwest African port on August 25, 1885, Göring set out for Otjimbingwe, the headquarters of the German Colonial Company. The settlement lay near the southern edge of a vast tract of grazing land that supported the huge herds of cattle that provided the diet – meat and milk – of the region’s leading tribe, the Hereros. In October, the Reichskommissar met Chief Kamaherero in his encampment at Okahandia.

As it happened, the meeting took place at a time when the Hereros were bracing for an attack by their traditional enemy — the Nama, also a cattle-herding people. Thus, Kamaherero found it hard to reject Göring’s offer of protection – a term which the chief took to mean that German forces would protect his people and their herds from the Nama, while to the Germans it meant that they had a right to be in the land and that German judges would be allowed to hear cases involving Europeans and Hereros. After a German flag had been raised at Okahandia and after Göring had filed a rosy report on the future of the protectorate, he returned to Germany.

January 1887 found the Reichskommissar back in South West Africa. It was the year of the “great gold rush,” which drew hundreds of new settlers to the region. (A rock face had been “salted” by shooting gold into it, a developer’s stunt in which Göring may have been involved.) By this time, Chief Kamaherero, having had second thoughts about accepting German protection, renounced it.

Worried about losing not only face but the protectorate as well, Göring asked Berlin for help: specifically, for a force of 400 to 500 men, plus field artillery. In response, a contingent of twenty-one men under the command of Captain Kurt von François disembarked from a British ship at the British-held Atlantic-coast enclave at Walvis Bay. The date was June 24, 1889. “Nothing but relentless severity will lead to success,” François wrote to a friend.” Bismarck, for his part, instructed the bristling captain that under no circumstances were troops to be used against the natives, but only to protect individual Europeans from the natives.

Faced with the Germans’ increased presence, together with renewed threats of Nama attack, Chief Kamaherero once again agreed to accept German protection. Thus encouraged, Göring sought to persuade the head of the Nama – Kaptein Hendrik Wittbooi – to fall in line. Wittbooi, who had been educated at Lutheran and Methodist mission schools, rebuked the Reichskommissar for trying to order him around in his own country. And he warned Chief Kamaherero, prophetically: “you will…forever regret having handed over your country and your governing rights to the white man….”

IV

As it happened, 1890, the year after Captain Kurt von François decided that “the conquest of the Wibooi was a necessary step in establishing effective German control of the land,” was also the year of the climactic encounter between the American government and the country’s indigenous people. This was the December 29, 1890, Wounded Knee Massacre, which took place on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, in which more than 250 Lakota men, women, and children were killed, as were twenty members of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry Regiment.

As in South West Africa, the goal was to clear the land of impediments for development by white settlers, both farmers and miners. The construction of the intercontinental railroad — begun in 1862, completed in 1869 – had been expedited by the policies devised by General William T. Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, who forced Native Americans who stood in the way of the railroad to live on reservations and wrote his brother that “all who cling to their old hunting grounds are hostile and will remain so till killed.” On another occasion, he said that “[D]uring an assault, the soldiers can not pause to distinguish between male and female, or even discriminate age.”

This policy had already been put into practice in California following the discovery of gold there in 1849. The Gold Rush drew an estimated 300,000 people to the area and, within the span of twenty years, resulted in the death of an estimated 80 percent of the Indigenous tribes. As Erin Blakemore reported in a June 19, 2019, History article, most of the roughly 16,000 victims were killed in “hundreds of massacres during which state and local militias encircled and murdered Native peoples in cold blood.” California’s first governor, Peter Hardenman Burnett, told the new state’s legislature to expect war “until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

On June 18, 2019, California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, formally apologized to the state’s native people: “It’s called a genocide,” Newsom said. “No other way to describe it.”

On November 29, 1864, fifteen years after the California genocide, the Sand Creek, Colorado, massacre took the lives of 230 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women, and children. The massacre was led by Army Colonel John Chivington; details of what happened on that day in November 1864 emerged the next year with the release of a Congressional Report on the Joint Committee on the Conduct of War: “From the suckling babe to the old warrior, all who were overtaken were deliberately murdered. Not content with killing women and children…the soldiers indulged in acts of barbarity of the most revolting character…. No attempt was made by the officers to restrain the savage cruelty of the men under their command, but they stood by and witnessed these acts without one word of reproof, if they did not incite their commission….”

In a November 24, 2014, Wall Street Journal article by Michael Allen, headlined My Great-Great Grandfather and an American Tragedy, Allen writes: “The United Methodist Church is investigating its culpability in the affair, given that key figures, including the commander, Col. John M. Chivington, were prominent members…. They want to reconcile how a man known for his Christian generosity could have been a party to such an atrocity—and whether they should feel any guilt by association.”

V

By 1892, two years after the Wounded Knee Massacre, Captain Kurt von François had acquired a new title, Landeshauptmann (national captain) and had built a fort, in Windhoek, 225 miles northeast of Walvis Bay. By this time, a trickle of German colonists had arrived, and it wasn’t long before Samuel Maherero, who had succeeded his father as chief, was complaining to the British magistrate in Walvis Bay that the Germans had forbidden him to buy arms, while, six months later, Kaptein Wittbooi wrote the magistrate complaining of the harsh German rule: “He introduces laws into the land [which] are…unmerciful and unfeeling. He has already beaten people to death for debt…. He stretches people on their backs and flogs them on the stomach and even between the legs, be they male of female….” Both tribes felt threatened and in November 1892 they signed a treaty that ended a conflict that had gone on for half a century.

Back in Berlin, meanwhile, the German Colonial Society had become a powerful lobbying group. Pressed by the Society and other nationalist organizations, the government responded generously to von François’s request for reinforcements, sending him 214 men and two officers, double the number he had expected. They arrived on April 3, 1893. At liberty to use the forces at his own discretion, von François decided that the time had come to carry out his “Plan of Action against Hendrik Witbooi,” although the Nama kaptein had given him no cause to attack, other than a refusal to accept German “protection.” The Germans surprised the Witbooi, expended 16,000 rounds of ammunition in the first half hour, killing eight-five Witbooi, the majority of them women and children, and returning to Windhoek with about fifty women and children prisoners. Landeshauptmann von François was convinced he had crushed the Witbooi once and for all. Not so. The Witbooi had simply withdrawn into the mountains to the south.

On January 1, 1894, Major Theodor Leutwein arrived from Germany with orders to strengthen “our military position vis-à-vis the natives.” In April he wrote Kaptein Witbooi asking if he wanted to continue the war or submit to German rule. Witbooi replied that he had no wish to continue fighting, but saw no reason for submitting to the Germans, particularly in light of the “terrible treatment” his people had suffered in the recent attack.

In July, 250 troops arrived, bringing quick-firing mountain cannon, and the uneven battle began. On September 9, having been forced to retreat to the last watering hole in Witbooi territory, Kaptein Witbooi surrendered. Kaiser Wilhelm II postponed signing the treaty until November 1895, after attaching a codicil that required the Witbooi “to respond unconditionally and immediately, with all men capable of bearing arms, to any call from the Governor…to resist external and internal enemies of the German protectorate.”

In their war with the Witbooi, the Germans had seized some 12,000 head of cattle, which could be doled out to the newly arriving settlers, with the White population of the colony increasing from 2,000 or so in 1896 to nearly 5,000 in 1903. Meanwhile, a railroad has been laid between the coast and Windhoek. Another was planned that would divide the Hereros’ traditional grazing lands and grant large blocks of land on either side of the track to the construction company. This mirrored the scheme of the American government, which had led to forcing tribes to live within reservations and resulted in the near eradication of the herds of buffalo, as fundamental to the economy of the Plains Indian as cattle were for the Hereros.

VI

In 1886 William Tecumseh Sherman wrote General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant: “First clear off the buffalo, then clear off the Indian. We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux even to their total extermination — men, women and children.” Grant acted with vindictive earnestness but stopped short of exterminating the Sioux. In South West Africa, the new man in charge of the protectorate, Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotta, on October 2, 1904, promulgated an extermination order, which read: “Any Herero found within the German border with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. No women and children will be allowed in the territory.”

Earlier that year, the Hereros had revolted against the increasingly repressive German rule, made all the more painful by the loss of their cattle to unscrupulous German creditors and to a disease called rinderpest. In the 1890s, the Hereros had herded more than 100,000 head of cattle; by 1902, the number had shrunk to half that number. Meanwhile, the merciless floggings continued, a practice defended by the settlers, who in a petition to the Colonial Office, wrote: “Any white man who has lived among natives finds it almost impossible to regard them as human beings.”

Chief Samuel Maherero listed the brutal treatment of his people as one of the causes of the revolt of his people. Before going to war, however, he issued an order of a kind never issued by an American officer, either in King Philip’s War or during the American Indian Wars. As Under-Chief Daniel Kariko later stated in an affidavit: “We decided that we should wage war in a humane manner and would kill only the German men who were soldiers or who would become soldiers.”

After killing more than 120 male settlers and German soldiers and tearing up rail lines, the Hereros withdrew to the north, with some 8,000 warriors, armed with antiquated weapons, protecting nearly 50,000 women, children, and the elderly as they moved slowly, with their herds, toward the butte-like mountain Waterberg. The 4,000 Germans enjoyed an overwhelming advantage in weaponry; after suffering heavy casualties, more than 1,000 Hereros, led by Samuel Maherero, escaped to the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (Botswana). A man who had served as a guide for the Germans described what happened after the battle: “All men, women, and children, wounded and unwounded, who fell into the hands of the Germans were killed without mercy…. and all stragglers … were shot down and bayoneted.”

Two months after von Trotta promulgated his extermination order, pressure from Germans settlers – who needed slaves to do their hard work on cattle stations and in the mines – the order was rescinded. By late 1905, about 8,000 emaciated Herero men, women, and children drifted in from the bush, only to be put to hard labor or held in concentration camps, where several thousand Herero and Nama died of starvation and disease in what became known as the first genocide of the twentieth century.

In 1908, Dr. Eugen Fischer, a docent in anatomy at the University of Freiburg, traveled to Southwest Africa to study the skulls of a mixed race people, the Reheboth Basters. In April 1933, the year the Nazis assumed power in Germany, Interior Minister Herman Göring – the youngest son of the former Reichskommissar of Southwest Africa – was charged with tracking down children born of sexual relations between German women and Black occupation troops following World War I. Three-hundred and eighty-five mixed-race boys and girls were subsequently sterilized. In 1934, Fischer began instructing SS doctors on racial issues at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology in Berlin.

VII

In 1907 – more than a quarter of a century before Dr. Fischer began teaching his class of SS doctors – the state of Indiana adopted a eugenic sterilization law designed to prevent “confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles, and rapists” from reproducing. California, Connecticut, and Washington quickly adopted similar laws. In 1922, a 500-page report written by Harry M. Laughlin, a champion of eugenical sterilization. It began with a warning by Harry Olson, chief justice of the municipal court of Chicago: “America, in particular, needs to protect herself against indiscriminate immigration, criminal degenerates, and race suicide.” Two years later, the U.S. Congress passed an immigration act crafted to enhance immigration from northern European countries, while suppressing immigration from southern and eastern European nations. By this time, fifteen states had passed sterilization laws, with Virginia going a step farther with the passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, making it “unlawful for any white person in [Virginia] to marry any [person] save a white person.” An exception to this rule was the Pocahontas Clause: “persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons.” (Forty years later, thousands of Native American women were sterilized without informed consent.)

In 1927, the Supreme Court upheld Virginia’s sterilization law – designed in part by Harry Laughlin — in Buck v. Bell, with Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., ruling for the majority: “It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.” He concluded his argument by stating, memorably, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” In a 1984 Natural History essay titled “Carry Buck’s Daughter,” evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould demonstrated on what flimsy and fraudulent evidence the case was made. Of Vivian Buck, the youngest of the three generations of Bucks deemed unfit to bear children, Gould writes: “This offspring of ‘lewd and immoral’ women excelled in deportment and performed adequately, although not brilliantly, in her academic subjects… [and] was on the honor role [at Venable Public Elementary School in Charlottesville] in 1931.” As for Vivian’s mother, Gould cites a Virginia scholar reporting that “mental health professionals who examined her in later life confirmed my impressions that she was neither mentally ill nor retarded.”

In May 1936, five years after Vivian made the honor roll in elementary school, Harry Laughlin, the industrious shaper of America’s compulsory eugenics legislation, was offered an honorary degree as Doctor of Medicine by Carl Schneider, dean of the faculty of medicine and professor of racial hygiene at the University of Heidelberg. The honor will be “doubly valued,” Laughlin wrote Schneider, “because it will come from a nation which for many centuries nurtured the seed-stock which later founded my own country….” In The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism, Stefan Kühl notes that Schneider “later served as scientific adviser for the extermination of handicapped people in Nazi Germany.”

For a time in the 1930s, Germany and America were locked in an ideological embrace regarding the implementation of genetic principles. The embrace became an embarrassment in September 1935, two years after the Nazis assumed power, with the passage of the so-called Nuremberg laws, one of which ruled that only persons of “German or related blood” could be considered citizens, while another proscribed marriages between Jews and citizens of “German or related blood.”

These were the first steps toward the Final Solution.