There’s no reason I should remember the Whole Foods shopper. He didn’t tip extravagantly like the men who were excited by my relative youth or my willingness when it came to Greek. I wasn’t scared of being recognized, as I’d been when the client looked exactly like the father of a fifth-grade classmate at the Jewish day school I’d attended a half-hour’s drive from Duluth. The Whole Foods Shopper wasn’t like any parent I’d met or would meet for another decade, when I would take my current job as a teacher in a laid back neighborhood of Santa Barbara. The other time I was scared of being recognized was when my driver dropped me off at the home of a client who turned out to live two blocks from my Jamaica Plain apartment, but the Whole Foods Shopper I met at the anonymous ground of the Omni. Meeting at the Omni isn’t memorable because it was one of my regular haunts, but I was annoyed, as usual, when my driver wouldn’t come to the valet with his car full of condoms and lube and baby wipes and perfume and extra thongs and heels, his trunk with enough cash and weed inside to make it clear he dealt. Instead, he dropped me at a curb by an overpriced seafood place, and I had to wobble across the street in my stilettos, careful not to fall over on the German and Swedish and French Canadian tourists who munched from boxes of clam strips as they walked.

When I’d made my way around the hotel’s many corners and into the first-floor room, I found the Whole Foods Shopper sprawled on the bed, a purple Hawaiian shirt half-unbuttoned, boxers on, jeans hung from the headboard. Long white hair, long white beard, neither the hair nor the beard slicked back or tied up or trimmed. He was smoking, but it wasn’t a smoking room. His Whole Foods bag sat on the dresser. That he would bring groceries at all was not memorable, since my clients were people with outside lives and errands to run, but I was struck by how perfect it was that this crunchy, unkempt man would, in fact, patronize Whole Foods. Then I was struck by the idea of a Whole Foods patron who still smoked. Probably he’d picked up the habit young, before going organic. The room smelled not only of his cigarettes but of rubbing alcohol.

With the smells, the clothes, and the groceries, his hair and beard streaked across the pillow, this corner of the Omni felt like his space, not mine. Outcall is like that.

The first word out of his mouth was “Hi.” This messy old man who probably listened to the Rolling Stones couldn’t be married. A wife would buy him new shirts and teach him to smoke outside.

Instead of saying hi back, I smiled with my mouth closed—this smile made me look mysterious when I practiced in the mirror, but mostly I didn’t want anyone to see my bad teeth. I unbuttoned the front of my dress just enough and wiggled and shrugged it onto the floor. Sometimes when I wiggled out of my clothes they would get caught on my ass, but not in a bad way. My ass, so many had assured me, was my best feature. A client who owned pizza parlor used to slap me there and tell me I was a prosciutto. Even today, the kids in my kindergarten class touch my ass and tell me it’s too big and round for the rest of me. Then I have to keep a straight, stern face as I explain boundaries to them again, for the umpteenth time.

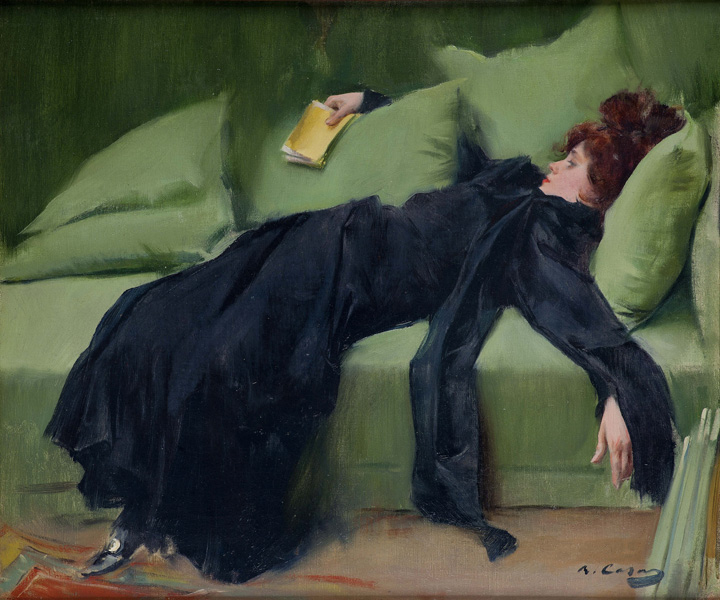

Even my one-time ex, who’d refused to take joy in anything, had been a fan of my ass. A year before I met the Whole Foods Shopper, I’d left this ex in Minnesota, more specifically Minneapolis, where he’d convinced me to move so we could experience what he called “a real city.” He was a goth who pretended to be poor, wearing cheap, clumpy black eyeliner and ratty tulle skirts even though he knew how to code and made a hundred twenty thousand dollars a year. But I’d convinced myself we’d be together forever. I still loved him long after it was over, even there in the room where the Whole Foods Shopper watched me undress.

“Hi,” the Whole Foods Shopper said again. His eyes were on me, a lump formed on the sheets where his dick strove for the ceiling.

“Hi.” I’d planned to straddle him without saying a word. Most clients told me later my pre-sex silence was erotic, magnetic, so hot. Only the Whole Foods Shopper wasn’t going for it. He wasn’t memorable for this; sometimes men just want to say hi.

“You know you’re gorgeous, right?”

I didn’t know, but on the off-chance he wanted me to know, I said, “Yeah, you’re lucky.”

He made an earthy, humored sound, but he was tense about something. I thought he was about to confide in me. Maybe he did have a wife. I remember the client in Jamaica Plain had a wife. He cried about her for most of our hour while I held him. I sympathized. The reason my goth ex had dumped me was I cheated on him. Sometimes you’re sorry even as you do the thing.

“You’re here of your own free will, right?” A few men had asked me this before, but not enough to make me feel good about the world. “I try to be an ethical consumer.”

I wasn’t sure if the Whole Foods Shopper was joking, but I told him, “I chose to be here. The agency has a strict application process. They also fire any girl who’s on drugs.” This was true, I wasn’t even allowed to touch the weed in my driver’s trunk.

The Whole Foods Shopper stubbed out his cigarette on a saucer on the nightstand.

The sex was unremarkable. Maybe he ate me out for a few minutes, as most men did, and told me, as most men did, “I bet the other guys never do that.” He was either fast or very fast, I have no idea now. All I registered was that when he took off his clothes, the rubbing alcohol scent got stronger, and I felt bad for whatever effort he’d made to get rid of his body odor on account of me, someone who was obligated to pretend he smelled good in any case. But the rubbing alcohol isn’t why I remember him. He wasn’t at all unusual in trying to impress his teenage escort.

He was chatty, though not the chattiest. When it was over, he asked if I believed in a religion. This also isn’t why I remember him; all sorts of men wanted to talk about religion because they wondered if they’d done something unholy with me. I’d recently had a troubling experience with a priest to whom I’d admitted I was Jewish. The priest had wanted to convert me, so he’d locked me in the room until our time had run out and my driver was banging on the door. After this, the cheerful woman who ran my agency assured me the priest had been blacklisted.

The incident with the priest being fresh in my mind, I answered the Whole Foods Shopper’s religion question vaguely. “I believe,” I said. I didn’t tell him in what. Even if I’d been comfortable, I was raised never to say that word, the g-word, because it’s too holy to toss around.

“In Jesus? Something else? I’m agnostic, just curious. Why are you standing?”

I’d stood up without realizing because the g-word question got me tense. Now I softened and got back in bed. I tried to climb on top of him in case he wanted to go again, but he lifted me bodily into a resting position. We sat there propped up on hotel pillows with our arms touching, the shared comforter over our bodies, the way I imagine married couples do. Not that I would know much about marriage, but I look at my students’ parents sometimes, and they seem like they’d lie in bed just that way.

“I believe in hashem,” I said.

The Whole Foods Shopper didn’t ask who hashem was. He picked up a new cigarette and lit it. “What’s your name?”

“Juliet.”

“That’s your name on the website. What’s your real name?”

I told him my name was Catherine, which is still not true but closer to the truth. He told me his name was Robert but I could call him Bob. I must have rolled my eyes, because he reached over to his pants and dug out his wallet. His driver’s license really did have the name Robert on it. I still think of him as the Whole Foods Shopper.

“Catherine,” he said, “you’re so young. You’re spiritual. You’re not doing this forever?”

I had no idea what I’d be doing forever, but I said, “Of course not. I might go to school.”

“The website says you’re already in school.”

“I was, but I took this semester off.”

He pretended to believe me. “What would you go back to school for? What do you want to be when you grow up?”

I couldn’t come up with anything worth saying out loud.

“Seriously.” He poked my rib. “I’m old and wise, I promise. Tell me what you want to do and I’ll tell you how to get there.”

“I want to be a writer.” I hadn’t admitted to this ambition before. Not even to my goth ex, who thought he was a poet.

“I know Tom Clancy.” The Whole Foods Shopper turned his head to gauge my reaction.

“Wow.” I made an O with my mouth sort of like the O I made for blowjobs. I was being lied to, but didn’t mind. I was touched that the Whole Foods Shopper would bother to make up what he thought was a better version of himself.

“I couldn’t introduce you. It’s the situation. Tom would ask how we know each other.” He took a long drag on his cigarette and blew the smoke away from me. “But he and I talk a lot, so I know how that world works. They have graduate degrees in writing that help people, so you should do that. Agents and publishers don’t even care who you are unless you get the degree. That’s how the game is played.”

I don’t remember the Whole Foods Shopper for trying to give me advice. Lots of men did that; imagining themselves as paternal soothed something.

“You have to go to undergrad first,” he said, “before you can go to grad school. You have to keep your eyes on the prize, even when your bachelor’s feels like something the world imposes on you.”

I don’t want to believe this, but it’s possible I remember the Whole Foods Shopper because these words helped me. I did end up reenrolling at the same university I’d already dropped out of once since moving to Boston and eventually graduated with honors. I don’t want to give the Whole Foods Shopper too much credit. I only want to credit myself. But there it is. He spoke about graduate school as if it were something real people did, and five years later I was working on a master’s in education. Not the writing degree he was trying to tell me about, but a degree that may still make me a vice-principal if I play my cards right. If the unpleasant woman who has the job right now gets sick or retires.

After mentioning graduate school, the Whole Foods Shopper got up. I checked the clock on the nightstand next to his stinky cigarettes and was sad. I figured he was letting me know I should leave, but there were still fifteen minutes left. I felt rejected, even if that’s stupid to feel with a client. I didn’t want to sit in the lobby being stared at by bellboys until my driver came back.

I leaned over the edge of the bed to find my panties, which were the same beige as the hotel carpet. His dick caught my eye, flopping the way dicks do. I hadn’t had a chance to look clearly before—he’d grabbed the condom out of my hands and rolled it on so fast. I like to tell myself not looking this one time was a fluke. I usually did look, just to make sure the clients didn’t have visible infections, not that anybody before had been stupid enough to book me while they had running sores.

I saw the Whole Foods Shopper had shaved poorly, and that the base of his dick was freckled with irritated dots, which ran over and down his testicles. Or no, those were breaks in the skin. I was looking at something wrong, something dangerous. Someone had in fact come to see me with sores. The Whole Foods Shopper. That’s a reason to remember someone, I guess.

He caught me staring. “It looks gnarly because they had to freeze the rash off, but it’s not contagious.” Maybe he’d convinced himself this was true. Men can talk themselves into anything, in my experience.

“Molluscum. It’s a thing you can get from towels, not like a real disease.”

I didn’t know what to believe. If I’d looked molluscum up on my phone right there in front of him, he might have left a bad rating for me on BigDoggie or The Erotic Review. I was pretty sure my goth ex had mentioned getting molluscum from someone at Burning Man, and I knew my goth ex was okay, so I figured things were okay. Anyway, the Whole Foods Shopper looked more bothered with being stared at than embarrassed. If he wasn’t embarrassed, then there was nothing to be embarrassed about.

Yes, I know how stupid this was in retrospect. If he’d had a wife, she would have made him face the truth about molluscum. If he’d had a wife, he would have mentioned it in that moment, how he got molluscum by betraying her, how all men are betrayers and she shouldn’t expect better, how he was married, married, married, just in case I thought of getting attached. You wouldn’t believe how many times clients have told me they were married and therefore I couldn’t fall in love with them. Hundreds? A thousand? I couldn’t tell you the names these clients gave me, what they looked like, or why they thought I’d feel so romantic about them in the first place.

“It’s cool.” I was still scanning the floor for my panties.

“I’m not asking you to go,” he said. “We have, what, ten minutes? I’m just getting us a snack.” He reached into the bag and pulled out a plastic tupperware of Whole Foods grape leaves.

“I’ll stay, but I’m allergic.” What part of grape leaves could I even claim to be allergic to? The rice? The spices? The leaves themselves? I only knew I could get fat if I let myself, and time has proven me right, sort of. My belly is still small, but tube-shaped, poking forward just as much as it stretches side to side. “Skinny fat,” I heard the mean vice-principal whisper to a coworker the other week.

I don’t remember the Whole Foods Shopper because he offered food. So many other clients have fed me. Every time we met, one Russian guy would present me with a box of cordials in bright foil wrappers, so pretty I had to eat them even though I was scared about losing my figure. Another client who worked at the Entenmann’s corporate office always handed me a box of rock-hard chocolate-covered donuts as I walked out the door—I gave the donuts to my driver.

Having procured the grape leaves, the Whole Foods Shopper sat back down next to me on the bed in our married couple pose, lifted the comforter up over himself again, and started munching. His bare fingers were oily, so he wiped them on the blanket. It wasn’t his blanket, after all. His lips made intimate smacking noises. I was not only sure this harmless man couldn’t give me his gross rash, I was entranced.

“You don’t even want one?” he asked between bites.

“I’ve got snacks in the car.” This wasn’t really the case, but my driver would grab a salad during my next appointment if I asked.

“We didn’t really talk about the writing. Just about you going to school. Got any questions? I’d be a bad guy if I didn’t answer.”

“How do people get published?” I asked, even though I was certain I wasn’t talking to an expert. “What if I want to write a book?”

“You’ve got plenty of experience to draw on.” He brought his face in until it was almost touching mine and winked deeply. “You could write a column, and then the book would be a collection of your columns. Easy. But you’d have to use a pen name and be careful to never show the work to anybody except the publishers.”

“But how do I make it good if I can’t show it to anybody and ask what they think?”

“I bet it would already be good. You’re good.” He winked again. “But look, it doesn’t have to be excellent. Whoever publishes you would spruce it up. Tom barely writes any of his own stuff. The point is, you still have to be a person in the world. You may need to get a job walking dogs someday. You’d be in school, and your professors would be dirty old men like me. If they saw your writing and knew it was you, they’d get the wrong impression. People might talk.”

It was the first time I felt that weight bearing down, that dawning that I might be doing something irreversible to my chances. I’m positive I’m not a worse or different person, but I know exactly what other people think. What if my vice-principal, the one whose job I want to inherit, the one who hates me, goes digging into my past? What if the people at my synagogue find out? I hate Reform services along with Orthodox; I’d have to drive to the next town over to find another Conservative congregation.

The Whole Foods Shopper was not done telling me what to worry about. “You’d have to do me a favor, since I’m the one who gave you the idea for this column. You’d have to promise me something special, like I’d be the only man you never write about.” He popped one last grape leaf in his mouth, then pointed to his crotch with a shiny finger. “This stuff is all private.” I understood his pointing to mean our whole encounter was private, but the molluscum was extra private. “It’s personal, and it’s just one of those things. You’ll look back in a decade and think of me as some old weirdo who happened to give you a push in the right direction.”

He was warning me in his own way, the way the men who made a point of talking about their wives were warning me, not to get attached. He was just some old weirdo who couldn’t mean much to me. Maybe he didn’t have a wife but a much younger girlfriend, someone who didn’t have it together to buy him nicotine gum or send him to a barber but was still grateful for his benevolent chill.

“What if I just changed your name?” As I said this, I realized I didn’t have to worry about changing his name. I’d already forgotten his name. Whatever name I could think to write in some future column or story wouldn’t be his real one, almost for sure.

“You’d give away my identity without even realizing it. You’d say something about my birthmark or how I’m a friend of Tom’s.”

I hadn’t noticed a birthmark.

“What if it was a composite? Like if I smushed together a bunch of different guys into one character, and you were one of them?”

“You really know how to make me feel special.”

We sat there for a second.

“Promise me. Just promise,” he said.

“I promise I won’t write about you,” I said.

He wrapped me in his arms then. A real hug, the kind I’d needed all my life. I hugged him just as close. He dug his head into my shoulder and peered over my back and around both my sides. “I can see you’re not crossing your fingers.” Then he let go. He hadn’t really cared about the hug at all, just my secrecy.

The joke’s on him. I was crossing my fingers in my head.

From across the street came three long honks of what I’d learned to recognize as my driver’s horn. I’m not sure why he was always honking if he wasn’t willing to drop me off at the hotel proper, if he was so determined to stay hidden and un-caught, especially because the horn so rarely could be heard from the upper floors of the hotels where I fucked my clients behind soundproofed windows. I relied on clocks, or the alarm on my phone. But one thing I remember is that night at the Omni, on the first floor with the Whole Foods Shopper, the sound of my driver’s senseless honking came through crystal clear.

Not that this explains why I remember the Whole Foods Shopper. Sometimes I just heard the horn.

“It’s my ride,” I said.

“Head out before he gets mad,” said the Whole Foods Shopper.

I probably rolled my eyes a second time at the idea that my driver getting mad was something to care about. My driver was there because he didn’t mind doing something illegal and he dated the woman who ran my agency. When he’d saved me from the priest, my driver had yelled, but his wheedling pot smoker’s voice had made him sound like a kid. I’ll always be surprised the priest didn’t ignore him, just as I’ll always be surprised the priest didn’t kill me. I get that in the end, the priest only grabbed my wrists and wouldn’t let go and yelled things I didn’t understand about Jesus, but I still think he was working up to something more. He had those shark eyes that let you know people are wrong inside.

I was staring off into space now thinking about the priest. The Whole Foods Shopper cleared his throat to rouse me. He must have thought I didn’t want to leave him, because he said, “I had a good time. I hope you liked my tip.”

I hadn’t noticed a tip. I looked over at the night stand to see if there was an envelope.

The Whole Foods Shopper saw me looking and said, “Sorry, I meant my advice. That’s my tip. It’s a more meaningful tip, don’t you think?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Your column is going to be famous. I’ll know it’s you. You’ll be a great writer someday.”

In the car, my driver informed me that my next call was in Watertown—one of those annoying Greater Boston places that are technically close to everything and still somehow impossible to drive to. As we rounded the corner, I thought I saw the Whole Foods Shopper in a high window, but that’s impossible because he was on the first floor. It was only a reflection, a trick of the light bouncing off the side of the hotel’s dark glass windows, a trick of life, a trick of my own mind, which tricks me still.

I see him even now; I see the Whole Foods Shopper. I follow home strange men from bars, strong men in jeans who are the opposite of my long-ago goth ex, and the Whole Foods Shopper is there. He shakes his head because people from my synagogue or my school might see. People might talk. Or he gets playful. When I’m reading the weekly parshah at my synagogue, which I’ve been doing every month or so for seven years, he shows up in the first row of worshippers. His fingers make a perfect V, which he licks like a pussy. He shouts, “You have a lot of material!” Other times he keeps me out of trouble. He floats before my face when I hear my vice-principal gossiping about me through open door of the teacher’s lounge and can’t do anything about it because she’s my boss and I’m already a minute late coming back from lunch. He tells me not to fight her with my bare hands—which is what I really want—because I can’t rack up an assault charge. I still have to be a person in the world.

I’m not so far gone; I know he’s not really there. The Whole Foods Shopper has become my thoughts. He’s what I’ve known about myself since childhood, since my school took a field trip to one of the American West’s many abandoned Jewish cemeteries. Our teachers handed out crayons and encouraged us to make rubbings on the oldest tombstones, mostly women named Malka, candles in relief at the top, just under the ’פ’נ. Determined to be original, I found a woman named Riva whose stone had a bird instead. I held my paper tight in place, but it kept slipping, so all I got was a purple wash. In the end, embarrassed and frustrated, I held my paper against the smooth surface of a newer stone and used the sharp edge of my crayon to draw the birds where I thought they should go. Then one of the women on the field trip with us—a vice-principal, actually—came by and told me, “None of the graves here have that many doves, do they?”

She meant to say I’d cheated, and worse, I’d imagined something that wasn’t. There’d been one large bird, but somehow, in the last few minutes, I’d convinced myself I’d seen four little ones. I got weepy right away, which I was prone to do, and the vice-principal did her best to comfort me, patting me on the shoulder while failing to hide her annoyance.

It just felt so unfair to be in my brain. It still feels that way. I fool myself without meaning to. I can’t keep track of truth. There’s a world full of goth exes, Whole Foods Shoppers, drug dealers who also drive escorts from one place to another, vice-principals, even little kids who are flawed but at least see things the way they are. I’m jealous of these people, because all I can sense is unreal. All I see is too many birds, a man who could just as well be dead by now, the light bouncing off a million hotel windows. All I know is the wash and whatever I drew on top, the false impression and the story I made up to go with it.