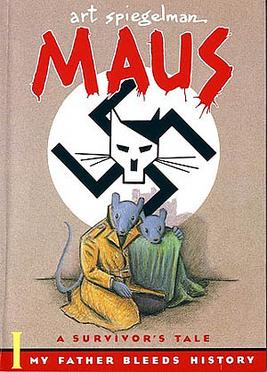

Many years ago, I got in trouble for teaching Maus, the Holocaust graphic novel. Not because of nudity or swear words, the reasons a school board in Tennessee gave for banning the book from its curriculum. At the time of the complaint, I’d read the book at least ten times, and I wouldn’t have been able to recall a single naked character or one instance of salty language. The parents of my student who objected to the book weren’t concerned about profanity, or pornographic pictures. They were terrified of how one particular theme might affect their psychologically frail daughter: suicide. And they were right to be concerned. Anyone teaching Maus to high school students should approach the novel’s suicides with care and sensitivity. These disturbing self-annihilations haunt the novel, and they’ve haunted me, and probably anyone who’s actually read and engaged with Art Spiegelman’s strange masterpiece.

Two suicides are central to the narrative. The first occurs in the terrifying “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” section, a separate graphic piece Spiegelman published many years before Maus, and then later inserted into the novel. The short, 4-page, black and white sequence – the only part of the story which features real human beings and not animals – portrays the suicide of Art’s mother and its aftermath. Art’s father Vladek, Maus’ chief narrator, finds his wife, Art’s mother, dead in a bathtub. Spiegelman draws himself here in a striped jail uniform, a prisoner not merely of his grief, but his maddening guilt, when friends and family imply that he was responsible for his mother’s death. A cousin scolds him, saying “Now you cry! Better you cried when your mother was still alive!” In the final panels, we see Art in a single cramped jail cell surrounded by an endless warren of barred cells screaming “You murdered me Mommy, and you left me here to take the rap.” The artwork for “Hell Planet” is as creepy, grotesque, and as nightmarish as the Auschwitz body piles in the later sections of Maus. The psychiatrist who informs Art of his mother’s suicide becomes a demonic, cackling skeleton. Gigantic coffins take over 4 separate panels. Spiegelman’s subconscious thoughts – “MENOPAUSAL DEPRESSION. HITLER DID IT! MOMMY! BITCH” – swirl through a panel depicting Art’s mother lying in a bathtub filled with blood. Ironically, the only subtlety in the section is also the one actual instance of nudity in the novel. Art drew his mother naked in the bathtub. But you have to study the images closely to notice the nude breasts. The other grotesqueries overshadow it. In 25 years of reading the book, I never spotted Anja Spiegelman’s naked body until I read the Tennessee School Board’s complaint.

Anja’s suicide is important to the novel because Anja’s story is the great unresolved tension in the book, the issue that perpetually divides Art and his father. Art interviews his Holocaust survivor father throughout the novel, but he also yearns to tell his dead mother’s story. He discovers that Anja kept a diary, and he becomes obsessed – “I have to find that diary”. When, at the end of Volume One, his father admits that he burned all his mother’s papers, Art explodes, clenches his fist, and seems ready to punch his father. He quickly calms down, but the last word in the volume, the first published edition of Maus, is Art mumbling that his father is a “murderer” – in other words that he murdered his mother by burning her diary. Why exactly did Anja kill herself a full 25 years after liberation? How did she experience the horrors that her husband Vladek Spiegelman described? We’ll never know, and that ignorance prevents any real reconciliation between father and son, and any remotely satisfying resolution in the novel.

The second suicide – possibly as important – is really a murder-suicide. Spiegelman depicts it just a few pages after the “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” sequence. In Vladek’s telling, he and Anja send Richieu their five-year-old child, to a “safer” ghetto, to live with relatives. When the Nazis are poised to liquidate that ghetto, Richieu’s aunt Tosha feeds the child and another cousin poison, and then kills herself. We can only imagine how this murdered martyred brother haunted Art’s childhood – a brother he never met. We know for sure that Richieu’s mini-Masada narrative loomed large for Art, because he dedicated the second volume of Maus to him, and included a real-life, non-animal photo of the boy on the dedication page.

The suicides form a lens which allow us to see other characters more sharply. For much of the book, Vladek is insufferable. He spooks the young Art with Holocaust horror stories. He nags and irritates his adult son over a host of minor issues – his coat, eating, a piece of wire. He plagues his second wife Mala with a never-ending stream of complaints. But he’s undeniably a survivor. He pedals on his exercise bike while Art smokes. He walks every day. During the worst of the Holocaust – homeless on Poland’s winter streets, or inhaling Auschwitz’s chimneys, he finds creative ways to survive. He’s the one who didn’t kill himself and with that bare fact he redeems himself and commands our sympathy. Similarly, Art is the brother who was not the victim of a murder-suicide. His life becomes painfully complicated because of his Holocaust survivor parents, but he’s never put in his brother Richieu’s position. Art, like Harry Potter, like his father, is the boy who lived.

It was the day after we read Richieu’s story that my student Ellen’s (not her real name) mother phoned me. She didn’t want to meet at my office in the synagogue because she didn’t want anyone to know she was seeking out a rabbi, her daughter’s confirmation teacher. So we met at Starbucks. She told me about her daughter’s anxiety disorder. How tied up it seemed to be with chronic depression. She’d never tried suicide, but she’d thought about it, and discussed it openly, terrorizing her parents. I ignored my steaming latte listening to Ellen’s Mom. My first response was okay, no problem, we’ll skip Maus. I’ll find something happy to read, maybe Moshe Waldoks Big Book of Jewish Humor. Or we’ll watch Mel Brooks movies. The idea of the class was to engage the students with Jewish ideas and identity, not depress them.

But Ellen’s mother said, no. Unlike the school board in Tennessee, she didn’t want to remove the book from my curriculum. It’s important, she said, to teach young Jews about the Holocaust. Several of her relatives were victims or survivors. Understanding what happened “over there” is an essential element of Jewish identity, she said, ignoring her tall black coffee. And you can’t teach the Holocaust honestly without bumping up against uncomfortable feelings – sadness, fear, rage, despair. Teach the book, she urged me. But don’t skip over the suicide scenes. Talk about them. Analyze what brings people to that level of desperation. Ellen, she said, needs to talk openly about her struggles. At least that’s what her therapist was recommending. And, in any case, she said, we can’t control what books Ellen reads in school, or at synagogue, or on her own. But if she’s going to encounter suicide in literature, better it be with a rabbi and sympathetic peers who can discuss the subject with wisdom and compassion.

I didn’t necessarily agree that knowing the Holocaust constituted an “essential” element in Jewish identity. I’d chosen Maus for that confirmation class because I thought it was a book of sly genius, and that teens would enjoy learning Jewish history from a comic book. But I did agree that if we were going to teach the Holocaust – and we were, we do – then we couldn’t elide unpleasantness. No trigger warnings could salve Babi Yar’s murder pits or Treblinka’s gas chambers or the massacres at the Warsaw ghetto.

Or suicide. Suicide is a not-so-hidden theme of Holocaust history and literature. Many members of the Jewish councils, whose job it was to provide lists of Jews for deportation, killed themselves, including Warsaw’s Adam Czerniakow and Vilna’s Jacob Genz. The suicide rates were high in the death camps. And what was the Warsaw Ghetto rebellion if not a mass suicide mission? And, perhaps most hauntingly for those who study Holocaust literature, several Holocaust writers died by suicide. Thane Rosenbaum noticed this and crafted a novel – The Golems of Gotham – featuring the ghosts of Primo Levi, Jerzy Kosinski, Paul Celan, Jean Amery, Piotr Rawicz, and Thadeus Borowski, all of whom survived the Shoah, wrote about their experiences, and then killed themselves years after liberation.

The phenomenon of the suicide writer suggests there’s a kind of long covid effect to the Holocaust, especially if you immerse yourself deeply into it. Thirty years later, the fumes linger, can still murder you, or induce you to murder yourself. This is all grim stuff, but Rosenbaum handles the material with surprising humor and grace. In Golems of Gotham, the revived writers comically transform Manhattan into a kind of anti-Holocaust theme park. Showers stop working. Tattoo parlors disappear. Striped clothing is outlawed. Even the New York Yankee pinstripes vanish, irritating shortstop Derek Jeter.

And there’s an unexpected happy ending. The first paragraph of the book describes a shocking suicide. A Holocaust survivor – protagonist Oliver Levin’s father – shoots himself while performing an aliyah in the synagogue on Shabbat. He spills blood and brains on the Torah. Seconds later his wife, Oliver’s mother, also a survivor, swallows a cyanide pill. Naturally, these suicides haunt Oliver, who’s already traumatized by a childhood listening to his parents’ tales of horror. He clings to normalcy enough to marry and father a child. But divorce and a writer’s block push him into a suicidal depression. His daughter Ariel, seeking to rescue her father, performs a kabbalistic séance, summoning the spirits of Oliver’s parents, who drag along the suicide writers. The book is funny but darkly cynical, sometimes verging on the nihilistic, especially in the character of Rabbi Vered, yet another survivor, who dedicates his life to denouncing God and religion, and later also kills himself. Until the last page, it seems possible, even likely, that Oliver will join his parents in suicide. But he doesn’t. Ariel’s spell works. The suicide ghosts turn out to be good fairies, spreading life instead of death. Oliver, in contrast to his parents, but very much like Vladek and Art, emerges as another boy who lived.

While discussing the suicides in Maus, I read Ellen’s confirmation class passages from The Golems of Gotham. I wanted to contextualize the suicides, demonstrate that it was possible to transcend the heavyweight of history, inject some measure of hope and light into this smoky subject, show that both Maus and The Golems of Gotham teach the possibility and importance of choosing life. Even though I wasn’t at all sure that was the point of either novel. I just thought it would help to throw a few laughs into the mix. And I wanted to reach Ellen.

Years later I asked her if I succeeded. We’d gotten back in touch during the pandemic when she found me on Facebook. She was getting married, and she wondered if I would perform the wedding – an informal ceremony, masked, in her parent’s backyard. I was delighted with the news and the request, and for weeks we traded Facebook notes on our lives. Since I was getting ready to teach Maus again, this time to a high school class at a Jewish day school, I asked her what she remembered about her confirmation class. “Not much,” she replied. “Those were horrible years. Honestly, I don’t think I paid much attention in class. I was only attending because my parents made me. I do remember that you were very kind to me. That I remember.”

Huh, I thought. I’d pretty much designed the curriculum for her, but she didn’t notice. I asked her if the class, or even just the book Maus, affected her thoughts about suicide. It took her several days to respond. “It’s funny,” she wrote. “I don’t remember being suicidal at all. I asked my parents, and they back you up; I guess I had threatened it, but I don’t remember doing so. I was probably making it up. Or I’ve blocked it out. But, honestly, even if I was genuinely suicidal, I don’t think a single class or book would have made a difference. But I don’t remember a lot from those times. Maybe you helped. Who knows?”

Indeed, who knows? I dropped the subject from our correspondence. But I was still attentive on the subject of suicide when I taught the class. I warned the parents and asked for their feedback. As Ellen’s mother had urged all those years ago, I lingered over the Hell Planet and Richeau sections of the book, leaving plenty of time for class discussion and engagement through assignments. When the news broke about the Tennessee School Board, I could only chuckle sadly. They’re concerned about nudity and swear words, and I’m up at night worrying about the suicides.

As it happened, the same semester I taught Mous, I also taught a course which dealt with the prototypical Jewish mass suicide story: Masada. I recalled that we used to teach the story as heroic defiance. But now, Jewish educators are encouraged to interrogate the story, suggest alternatives, and point out that the very agency the Masada victims employed in slaughtering each other could have been used for other choices. That semester, I also thought about the suicides in my family, my sister-in-law, mother-in-law, and the suicide note I found written by my mother – she never followed through with it, and we never talked about it. I’m besieged by suicide, I thought. But there’s no point in burying the subject, or engaging in denial. In our frighteningly connected, meta world, a world where teen anxiety has become epidemic, young people know all about suicide. It’s a terrible topic, but one we can’t ignore. And, I believe, it’s a key to understanding the Shoah, and the lessons we derive from it, particularly for this generation who will grow up never having met a survivor. If we’re going to teach the Holocaust – and we are – we of course must allow for nudity and profanity, but those aren’t the problem. The problem – one of the problems, at least – is suicide. Even so, we’ll teach it.

I couldn’t perform Ellen’s wedding ceremony. It would have involved travel, and, during those acute pandemic times, I wasn’t ready for that. But she posted photos from her parents’ springtime garden. With its red and white roses, thick, deep, green grass, and leafy oak trees, it was bursting with life. Under a virginal white huppah, a handsome groom, young and filled with energy, wrapped in a brand-new tallit, lifted the white veil from his glowing bride. Look at them, I thought to myself, a tear escaping from one of my eyes. Look at this young Jewish couple. Look at my former sad student, this rejoicing bride with the widest smile I’d ever seen. Look at her now. The woman who lived.