When future historians of Jewish culture look back at the late 2010s, they will mark it as the time when Gershom Scholem (1897–1982), the famous historian of Jewish mysticism, became celebrated as The Thinker Jews Need Now.

The “Jewish Lives” series of books sponsored by Yale University Press and the Leon D. Black Foundation published David Biale’s Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah over the summer. This is the fourth book about Scholem published in English in the last eighteen months. George Prochnik’s Stranger in a Stranger Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem and Amir Engel’s Gershom Scholem: An Intellectual Biography both appeared in the space of a single week in March 2017. This past January saw the English translation of Noam Zadoff’s Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back: An Intellectual Biography, originally published in Hebrew in 2015. It is also deeply important to note that in this time period, Miriam Zadoff’s 2014 biography of Scholem’s older brother Werner—under the English title of Werner Scholem: A German Life—also appeared. Much of its information about Werner Scholem, a Communist politician killed by the Nazis, comes from Gershom Scholem’s diaries and letters.

Scholem’s own scholarship is being reprinted in handsome editions as well. His 1000-page biography of the seventeenth-century pseudo-Messiah Shabbatai Zevi, reappeared in the fall of 2016 with a svelter look and a substantial new introductory essay by the Princeton historian Yaacob Dweck that traces the history of the book itself as a historical object. Biale has written a new foreword to Scholem’s Origins of the Kabbalah, which will appear this fall. Even some of the poems that Scholem wrote (mostly in diaries and correspondence) have been republished, under the title Greetings from Angelus.

Something is afoot. But what?

Part of the answer must be that what constitutes a properly Jewish life in the United States has now become utterly perplexing and mysterious. Support for the policies of the state of Israel is declining among diaspora Jews, especially younger ones, and social media has toxified debates about Israel. Religious membership in the US is declining (except among the Orthodox) as more and more US Jews are classified by the sociological term of artlessness, “just Jewish.” And as Jewish organizations’ fundraising appeals never cease to mention, intermarriage is on the rise.

At this anxious moment, Scholem’s biography has something to offer everyone. He refused to identify as a secularist, but when he discussed theology, he also refused to represent any Jewish denomination. He wrote about Kabbalah and inspired many in their own mystical journeys, but he himself was not a practitioner and was even cynical about the possibility of Jewish mysticism today. His youth was marked by an intense Zionism that jumps off of the page, but after he emigrated from to Palestine in 1923, he at times despaired that Zionism could renew the Jewish people. (His despair over Zionism is just as contagious as his Zionism.) He is perhaps the only person in Jewish letters whom all of your Facebook friends can respect, because they all can interpret him in their own image. His contradictions are ours.

We might feel ashamed and inauthentic because of our contradictions. But Scholem seemed to rise above such feelings, due to the sheer power of his intellect, will, and ego. He might today be described as a manic depressive: his self-importance was boundless (as a teenager, he briefly thought he was the Messiah), but regularly in his life mere existence seemed to be a great burden. But those phrases! They somehow remain generative because they are vague: “the messianic idea has compelled a life lived in deferment,” “Judaism has no essence,” “the secret life Jewish mysticism holds can break out tomorrow in you or in me.” They carry the power of their author.

Remembering Gershom Scholem is abundant with promise. But it is easy for these books to shatter that promise, as they go through the rhythms of Scholem’s life from his bourgeois upbringing in Germany, to his activity in Zionist circles, to his friendship with Walter Benjamin and the exciting philosophical ideas that germinated between them, to his emigration to Palestine, to his membership in the leftist binational movement known as Brit Shalom, to his scholarship on the Kabbalah, to his reactions to the Holocaust, to his conflicts with Hannah Arendt over the meaning of Zionism and the Jewish people, to his stature as the éminence grise of Jewish studies, to his death. They shatter that promise because Scholem was a bit—and likely much more than a bit—of a jerk. Perhaps in years past, readers might have excused the bad character traits of someone taken to be a genius. But they should not have done so then, and they should not so do now.

Because Biale’s Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah spends so much time detailing Scholem’s personal interactions, he ends up ironically being very good at making you wonder why you are spending time with his book at all. One of the first things Biale shares about Scholem is that he inherited his “volcanic temper” from his father. And the anecdotes keep coming. In 1923, the Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig reported in a letter that Scholem’s summer in Frankfurt—where he taught three adult-education classes before his emigration to Palestine—was marked by his being “unspeakably ill-behaved.” Scholem was frequently brusque and dismissive of many of his colleagues, and his intellectual companions in Israel remarked regularly on his insistence on always being correct.

Then there are the stories about women. Scholem’s diaries contain misogynist statements (“there is no female Torah”) dating back to his early twenties. During the same period, a young woman who was taking Hebrew lessons from him stopped because, as Scholem put it in his diary, “she is afraid of me.” While courting Escha Burchardt, whom he would marry in late 1923, he wrote in his diary that she “wants everything she can get: to be my lover, my wife, but all she really wants is to have children.” (Don’t be shocked, but she would later complain to him that he didn’t take her seriously.) When that relationship frayed within a decade of the wedding—in part, according to Biale, because Scholem either refused or was unable to have children—Scholem fell hard for a friend’s wife, Kitty Steinschneider. She refused him, and he stubbornly failed to get the message, writing her in the fall of 1934 that there was an “infinite and unexplained alienation that exists between us.” Scholem may have thought that the alienation was unexplained, but the true explanation will immediately strike every reader of Biale’s book.

In short, Scholem appears to have been That Guy. You know the one. The one who can’t take no for an answer. The one who insists that he deserves to have everything his way, because of the rarity of his intellect and the rarefied nature of his thoughts. The person who looks like an adult, but is really nothing more than an overgrown petulant child.

Even the master of the Kabbalah can be a master of douchebaggery.

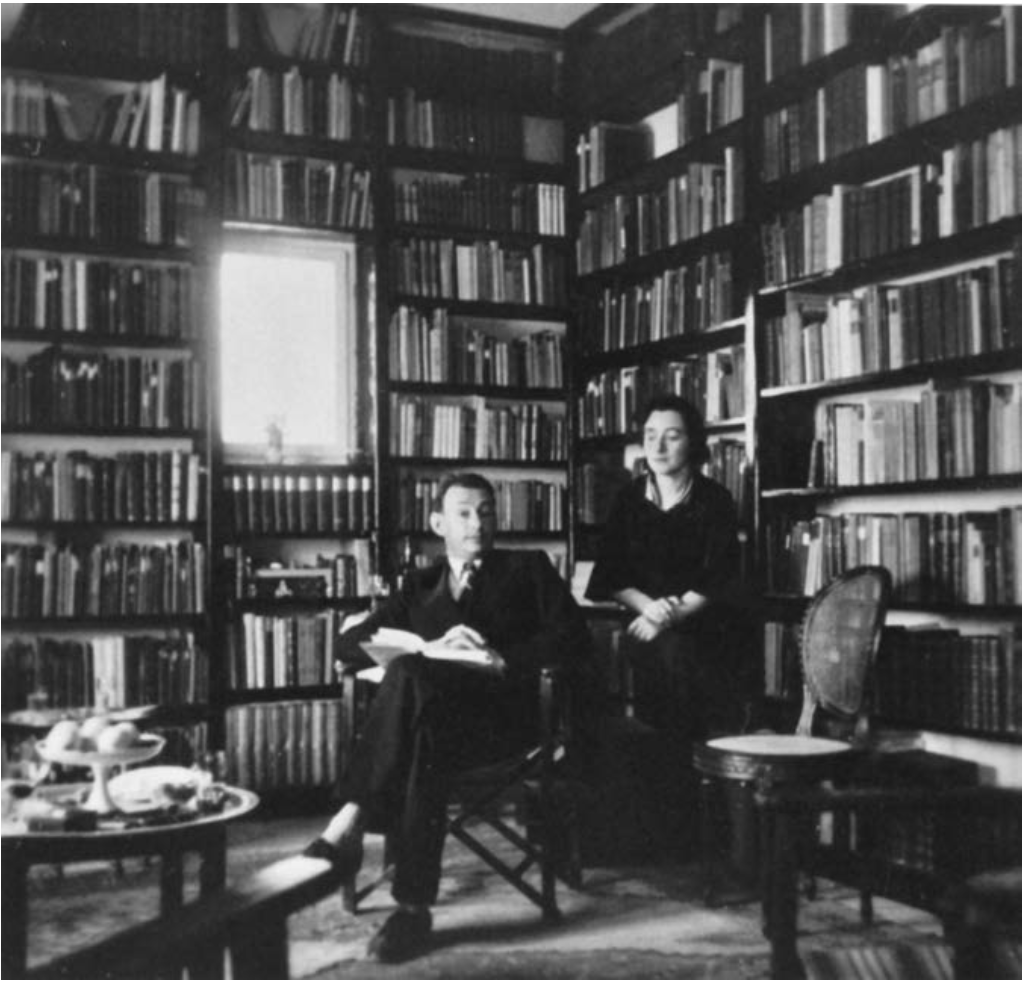

In its early pages, Noam Zadoff’s biography reproduces a photograph of Gershom Scholem and his second wife Fania in Gershom Scholem’s library at the home they rented in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem. They occupy maybe one-fifth of the image; the focus is clearly on the library, with books from floor to ceiling. Scholem is in the center of the image, sitting in a chair with legs crossed, a book open on his lap, head held high, flashing a self-satisfied smile at the camera. Fania Scholem stands behind him and to his left, her arms crossed demurely. She looks neither at the camera nor at her husband. She looks at the book in his lap. Perhaps she is jealous of its proximity to her husband. Perhaps at night, she dreams of Daphne—not because Daphne was freed from Apollo’s rapaciousness by being turned into a tree, but because Fania Scholem, unimaginable to any of the authors of ancient Greek myths, fantasizes about being chopped down and having patterns of ink strewn over her processed corpse. Then she will be affirmed. Then she will be loved.

Two of the chapters of Zadoff’s biography touch on Gershom Scholem’s love for books. Quoting Scholem’s 1916 description of his library (which eventually grew to comprise some 25,000 books) as his “best friend,” Zadoff suggests that Scholem’s bibliophilia was a manifestation both of a love of order and a Zionist expression of his love of the Jewish people. Books and manuscripts were, for Scholem, tools of resurrecting the dead after their destruction. This explains why he spent much of 1946 as part of a delegation recovering plundered Jewish libraries from many Nazi-related institutes. Zadoff painstakingly reconstructs Scholem’s travels throughout Europe—Hollywood screenwriters, get to your keyboards!—narrating the disappointments and the successes, focusing on the conflicts with the US Library of Congress and other US Jewish organizations as to where these books would be repatriated. Zadoff ends, as he should, with the dramatic sub rosa transport to Israel of the most valuable books and manuscripts that Scholem had found in the archival depot in Offenbach, engineered by a crafty American military chaplain and rabbi named Herbert Friedman.

Scholem may or may not have conspired with Friedman to take these titles out of Allied hands. But readers of this episode in Scholem’s life—whether the fifty pages in Zadoff or the three in Biale—should remain haunted by that image of Fania Scholem looking at the book in her husband’s lap. It is true that books have the power to give and sustain life; no one who has loved a book, whether it details the exploits of Rabbi Akiva or Babar the elephant, could ever say otherwise. But the kind of life they give is not the same as that of the persons in front of us. To make the category error of thinking that books are identical to flesh is to set a stage where Fania Scholem appears as library furniture.

There is a danger in loving Scholem too much. Prochnik’s Stranger in a Strange Land juxtaposes his biography of Scholem with a memoir of his and his wife Anne’s move to Israel. Prochnik presents himself as a Scholem fanboy, and his learned explanations of and enthusiasm for Scholem’s ideas concretize the depth of their motivation in the late 1980s for making aliyah, where religiosity could be better integrated with life. It starts out well, as all utopian desires do. But as Prochnik narrates the collapse of Scholem’s own Zionist idealism—most notably in a 1926 letter to Franz Rosenzweig (discovered after Scholem’s death) in which Scholem claimed that the revivified “Hebrew language is pregnant with catastrophe”—his own idealism falls apart as well. Suicide bombings. The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin. Fights between husband and wife. Once Prochnik has narrated the end of Gershom and Escha’s marriage—she leaves him for their neighbor, Shmuel Hugo Bergman, at that time the director of the Jewish National Library—the reader knows that George and Anne are next. It is the fanboyness that comes in for the greatest judgment, as if a marriage could have been saved had Prochnik not thought that reading Scholem’s 1936 essay “Redemption Through Sin” (nicely summarized by Prochnik as a commentary on “Zionism as a zombie morality play”) would reveal secrets that could explain why Rabin was shot, had he just read less, had he just loved people a little bit more than he loved books.

Character traits matter, in part because they circulate through a community. Reviews of books by intellectuals rarely mention them. Perhaps they should even lead with them. But how much weight should they be given? Too much, and the character traits will make the ideas seem as dirty as their author’s character. Too little, and the silence only ensures that bad character traits infect a community more rapidly.

I would like to suggest, with some fear and trembling, that Scholem’s ideas can show a way out of this impasse. Amir Engel’s book, the best of this lot in my view, presents Scholem’s thought as beginning with a youthful enthusiasm and settling into a mature caution. In his teens and early twenties, Scholem was an active member in Zionist youth circles in Germany, and regularly took his fellow Zionists to task for not being adequately rigorous in their Zionism. In the second half of 1918, he wrote a polemic farewell to the Zionist youth movement, not because he was giving up on Zionism but because he was giving up on others who thought they could be Zionists in Germany: “in exile there can be no Jewish community valid before God.” It remained too abstract, and was more concerned with maintaining the purity of its opposition to its anti-Zionist enemies. The desire for some kind of normalization of Jewish existence suffused Scholem’s early writings on the Lurianic Kabbalah, which were motored by loss (notably the expulsion of the Jews of Spain in 1492).

But once Scholem had immigrated to Palestine, Scholem had become suspicious of just what Zionism could accomplish. The letter to Rosenzweig from 1926, only three years after Scholem arrived in Palestine, remains the clearest example of this. It is most famous for its opening line: “this country is a volcano.” The metaphor of the volcano was already in use amongst those who had arrived in Palestine during the Second Aliyah (notably the author Yosef Haim Brenner) to refer to the danger posed to Jews by Arabs in Palestine. Scholem turned this on its head, arguing that the real volcanic danger lay in overly rapid Jewish secularization, because the religious nature of Hebrew was repressed in its day-to-day use so that, as Engel summarizes Scholem, “the deep layers of the language would turn on its users.”

What this turn would actually look like is not clear from Scholem’s letter, but Engel fascinatingly hypothesizes that one example was the influence that the historian and professor of Hebrew literature Joseph Klausner held in Palestine in the 1920s (and later in the state of Israel). Klausner, a right-wing Zionist Revisionist (who, as Adi Armon has recently pointed out in Haaretz, would become the mentor of Benzion Netanyahu, the father of Benjamin Netanyahu) wrote books and articles that described Arabs as quasi-savages, whose culture was a danger to Jews. In addition, Klausner described Zionism as a messianic endeavor. But such a utopian realization could only backfire, creating new forms of (Arab) resistance in the place of the (European) resistance that Zionism sought to overcome. The sure failure that Scholem saw in Klausner’s attitude led him to associate the right-wing Zionism of Klausner and others with the Sabbatian heresy, the messianic energy that circled the Kabbalist Shabbetai Zevi (1626–76) who proclaimed himself to be the Messiah and later converted to Islam. As a scholar of messianic heresy, Scholem saw the dangers of Zionism like few other Zionists of his time.

Scholem’s later work—not only his biography of Shabbetai Zevi, originally published in Hebrew in 1957, but also other postwar essays and books—was marked by an acknowledgment of what Engel rightly identifies as “competition between continuity and rebellion” throughout the Jewish tradition. Those books and articles are object lessons in how the intensity of a desire is magnified when one assumes that a stance of rebellion is the truly traditionalist stance, without any heretical element—whether in Zionism (and Scholem’s own youth), in Sabbatianism, or in medieval and modern Jewish rationalism—and then how that intensity exhausts itself and collapses, causing no small amount of harm in the process.

Engel suggests that Scholem gave “no concrete answers” as to what would be the most stable future for Zionism, or for Jewishness: “like most of us, he simply had none.” This certainly may be true. But Scholem’s late writings do not give up on the belief that the Jewish people might figure out an answer that might last for awhile. In a 1974 essay entitled “Reflections on Jewish Theology,” Scholem waxed somewhat rhapsodic about Zionism between secularity and religion:

I regard it as one of the great chances for living Judaism—indeed, the decisive chance—that it does not attempt to evade this choice with easy compromises, but rather that it faces it openly and in the unprotected arena of historical engagement. In other words, I am convinced that behind its profane and secular façade, Zionism involves potential religious contents, and that this potentiality is much stronger than the actual content finding its expression in the ‘religious Zionism’ of political parties. Why? Because the central question about the dialectics of living Tradition will be more fruitfully posed in Israel with an element of doubt than in the manner it is posed there from a position of strength, fortified today by cowardly laws.

In other words, what Scholem rejected in the Jewish tradition (but spent his scholarly life trying to understand) was certainty. This was not a recipe for quietism or nihilism. It just meant that one needed to dare to move forward in a way that was sensitive to the real debates about a position—and that did not hide in fictions about powerlessness or justice or nobility, abstractions that are still present in discourse about Israel today (not least in the rhetoric about contemporary Birthright tourism). In addition, one needed to be aware that an action could be justifiably interpreted in a variety of ways, transcending ideological purities. An apparently secular act could be creatively linked with the Jewish tradition, or a value it holds dear, in line with the fact that the divine word, as Scholem put it in a 1970 essay, “is infinitely interpretable and reflects itself in our language.” An apparently religious act could likewise be interpreted as a departure from tradition. The circulation of those interpretations in a nation serves as a necessary moderating force on its actors, and keeps utopian dreams from dying an early death. But no one, not even Scholem, could say in advance what the results of that circulation of ideas would be.

This story of Scholem’s intellectual commitments yields a few important imperatives that arise from his realization that Jewish history serves as a warning against certainty. Certainly you should dream of something, and dream that the future will be something different from and better than the present, but be wary of the intensity of the desires behind such dreams. Hope for success, but be scared of it too, especially when success comes at the cost of others’ desires, and intensifies them as a result. Increase your power, but be sure to share it. Find as many ways as possible for the past to endorse your present loves, but do not forget that the books of the past serve the present moment.

Those principles, the ones we need now, have clear consequences for the Palestine/Israel conflict about which Gershom Scholem so frequently wrote. But they can also be applied elsewhere. In my dream, Gershom Scholem acknowledges those principles while he sits in his library. He wipes that annoying smile off his face, gets a chair for his wife, and Fania Scholem attains the fullness of humanity denied her by this photograph. In that room, they read books together, and she teaches him—and us—a thing or two. They even occasionally close their books, have a conversation about some secret that no scholar could ever unveil as truth, and let each other know that there are more important things in the world than books. May the world signified by that dream come to pass speedily and in our day.

__

Martin Kavka is Professor of Religion at Florida State University. He is the author of Jewish Messianism and the History is Philosophy (2004) and the co-editor of four volumes on Jewish thought. He is currently completing a manuscript entitled The Perils of Covenant. This is his first contribution to Tikkun.

Gershom Scholem had conflicted vulnerabilities.

Education is a fool(s) gold.

Certainty is transient.

Harmoniously we shall live or not at all.

Humanity will thrive in spite of it(s) shortfalls.

Susan Irene Platt 7-27-18