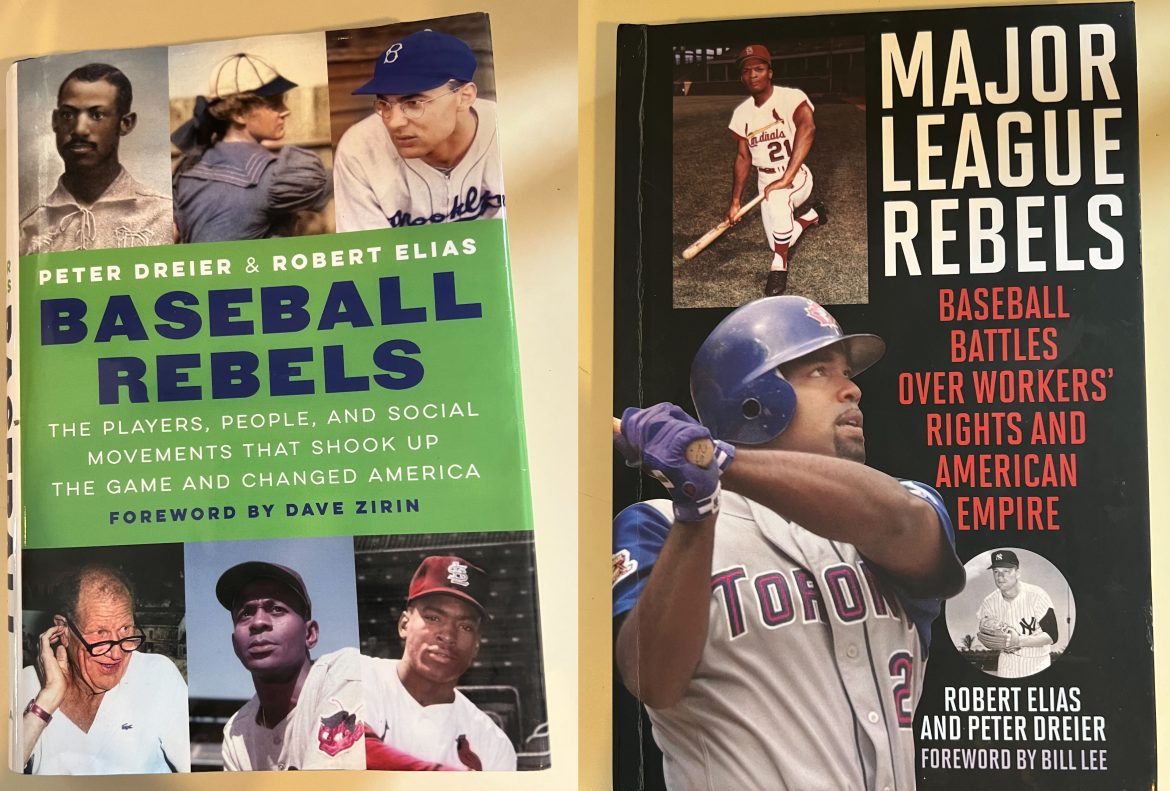

A review of Baseball Rebels: The Players, People, and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America (University of Nebraska Press, 2022), Peter Dreier and Robert Elias, Foreword by Dave Zirin and Major League Rebels (Rowman and Littlefield, 2022), by Peter Dreier and Robert Elias, Foreword by Bill Lee

In 1977, scholar/activist Harry Edwards was initially denied tenure in the Sociology Department at the University of California at Berkeley. After a protracted public struggle, he won his battle for tenure. Many of his fellow academics maintained that too many of his publications were “more journalism than scholarship.” That was always code language for “he appeals to public audiences.” As a young faculty member at Berkley at the time, I joined the protests for Harry Edwards. All too often, I heard disrespectful and even snide comments from faculty that Edwards’s focus on the sociology and politics of sports was somehow trivial and not worthy of inclusion in a great university. Those comments also reflected the general faculty’s unease with public political activism.

That was nonsense. It was a variant of the tired cliché that sports and politics don’t mix, itself a thoroughly, if unacknowledged, conservative posture. Harry Edwards is a pioneering figure in locating athletics in their broad social, political, historical, and economic context and the foremost scholar of sports in the United States. Likewise, he has been a tireless advocate for Black athletes and the architect of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which led to the courageous Black Power salute by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics––the moral highlight of the modern Olympic movement. This was an early example of civil rights activism and preceded Colin Kaepernick’s equally courageous decision to kneel in 2016 before the national anthem at the start of NFL games. A large body of critical scholarship and journalism has documented this historical activism.

Baseball has hardly been immune from political controversy and turbulence for well over a century. It is much more than an enjoyable national pastime, a recreational respite from daily stresses and problems. The Society for American Baseball Research has published multitudes of books and articles and sponsored annual conventions and other events. Baseball is a fit subject for serious analysis. And now scholars Peter Dreier and Robert Elias have published two powerful companion books detailing the people and movements that fundamentally shook up the game, changed American labor relations, and even challenged American hegemony and empire throughout the world.

Baseball Rebels and Major League Rebels emerge from two highly accomplished scholars who are also lifelong baseball fans. These books are superbly researched and richly detailed, providing readers (especially baseball fans) with a treasure chest of knowledge. These books are outstanding additions to the literature of interdisciplinary baseball scholarship. The works address the long economic, political, racial, gender, class, and related battles of baseball. The authors identify and elaborate the key players from the mid-19th century to the present.

Baseball Rebels explores how activists have challenged the status quo and added to America’s rich tradition of political and social dissent. Not surprisingly, the earliest resistance struggles opposed racism because baseball––entirely in the 19th century and mostly even now––was dominated by rich white men. I’ve been teaching about the horrific racist reality in our country for a long time, focusing mostly on institutions like the government, the police, the law, and corporations. Now, with the help of these books, I can add baseball to the infamous list of racist enterprises. This should be an engaging dimension to my longtime pedagogical commitment to antiracism, a feature of critical race theory that I have employed in many of my UCLA classes for as long as I can recall.

The battle against baseball segregation began long before Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Dreier and Elias bring attention to figures that most people have never heard of, including myself. Octavius Catto was an intriguing early figure in combating segregation in “America’s pastime.” He fought relentlessly for his fellow Blacks in Philadelphia in every civic realm, but especially baseball, where he was a star player on a Black team, an initial predecessor for the emergence of Negro League baseball. Catto believed that integration would allow Blacks a major hedge against all forms of racial discrimination. But while campaigning for Black voting rights in 1871, he was brutally murdered at age 32 by a white man. Now a century and a half later, Catto’s crusade for minority voting rights remains as perilous as ever, as state legislatures move to impede minority participation in the electoral process and chip away at American democracy.

Other African Americans played roles in the long battle for racial justice in baseball. Moses Fleetwood Walker managed to play a major league game in 1879 because of his light skin. He too was later attacked by white men and became a Black separatist like Marcus Garvey. Eventually, the Negro Leagues were formed, as the authors show, as a direct part of the emerging New Negro Movement and the 20th century civil rights ferment. What is especially significant and informative to scholars and general readers alike is that the emergence of institutionalized Black baseball should be understood in the context of African American resistance history generally.

A valuable chapter in Baseball Rebels is “Before Jackie Robinson.” Many people even now think that Robinson was brought to the Dodgers as a result of the moral vision of owner Branch Rickey. Not so: there had been considerable agitation to break baseball’s color line for years before he entered the major leagues. A huge barrier was the Baseball Commissioner, Kennesaw Mountain Landis, an implacable foe of integration and a deep-seated racist. But many journalists and political activists, including Paul Robeson, joined the crusade. The authors highlight the central role of Communist Party Daily Worker sportswriter Lester Rodney, who waged a tireless campaign on behalf of Black players. This book is a major step in restoring Rodney to his proper historical recognition, an immense scholarly service.

The authors likewise identify maverick owner Bill Veeck as one of the few heroes. If Veeck had had his way, major league baseball would have integrated five years before the Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson. Rodney, Veeck, and a few others noted in the volume set the stage for Robinson’s historic entry in April 1947. His story is well known and the book details the horrific conditions he endured during his initial year. Like Blacks everywhere, especially in the South, he encountered many daily humiliations and suffered hostility from other teams and fans, with constant death threats and screams of racial invective. This also occurred from some Dodger teammates, although others came to his defense and became his friends. Many readers still don’t know about Jackie Robinson’s post-baseball activism. This is well detailed in the books and reveals the longer history of athletes as activists, long before Colin Kaepernick made his historic anti-racist stand and long before he was born.

There are also valuable sections on Larry Doby, the forgotten second African American to enter the big leagues and the legendary Satchel Paige, who joined the Cleveland Indians in 1948, well past his prime. Paige had been the star pitcher in the Negro Leagues, compiling one of the most outstanding records in all of baseball history. This early racial integration was not easy. Black players continued to experience indignities on and off the field, a reflection of the deeper racism embedded in American society and history.

The key figure, however, was St Louis Cardinal outfielder Curt Flood, who several decades later in 1969, decided to refuse his trade to the Philadelphia Phillies and filed suit against major league baseball against its reserve clause.

The reserve clause in professional baseball (and other professional sports) was an integral feature of the contract between the teams’ owners and the players. It stated explicitly that the team retained the rights to players until the contract was terminated. That meant that players were not allowed to enter into a contract with any other team, therefore binding them to their team alone. The reserve clause allowed teams to trade, reassign, sell, or release any player at their sole discretion. The players’ only power was to refuse to sign their contracts and hold out, usually for more money. Sometimes they asked to be traded or released so they could sign with another team. In essence, players had almost no freedom.

Despite all odds and against the advice of many close friends, Flood sacrificed his career by challenging this clause that restricted players to one team only. He objected to being treated like a piece of property. With the assistance of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), and its heroic executive director Marvin Miller, Flood filed suit to overturn the clause. He failed when the Supreme Court declared that it was up to Congress to fix the situation. But in 1975, the MLBPA finally prevailed in an arbitration allowing players to be free to negotiate with other teams. This has paved the way for revising a century of labor/management relations and dramatically increasing players’ salaries.

Part two of Baseball Rebels addresses the historical and contemporary challenges of sexism and homophobia in baseball, mirroring society in general. The public at least knows the vague outlines of women’s professional baseball leagues, but the book provides valuable detail. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) from 1943 to 1954 was the key institution. Itself sexist with absurd dress and behavior codes for players, provided a unique opportunity for gifted women athletes. This remarkable book tells the story of pioneering figure Helen Callaghan in the league as well as lesbians in the AAGPBL. Although none of the women could be open at the time, this was a rare opportunity for a few gay women to participate in professional baseball. The league likewise struggled with racism, not integrating even after Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. The AAGPLG was memorialized in the Hollywood film A League of Their Own in 1992, providing the public with some popular culture exposure to a long-neglected feature of American history. Baseball Rebels fills in some major gaps with a solid scholarly focus and vision.

The authors continue by showing the further progress of feminism with an account of girls’ progress in entering Little League baseball, professional umpiring (not yet at the major league level), and in the executive ranks of professional baseball. Similarly, women have entered the field of sports journalism and broadcasting, once again eroding hegemony in these areas. As in every other feature of American life, the reduction of patriarchy is slow, tedious, and regularly frustrating. The book chronicles that process admirably.

The chapter on Gay Men in America begins with a distressing fact: “no gay player has ever publicly acknowledged his homosexuality while still in uniform.” This is regrettable even as LGBTQ people have advanced significantly in other sports, especially women’s basketball, soccer, and tennis, including such stars as Brittney Griner (still unjustly imprisoned in Russia), Megan Rapinoe, Billie Jean King, Martina Navratilova, and many others, men’s swimming, like Greg Louganis, and a few former professional football and basketball players who came out after their playing days. Advances in just about all other fields have been far more significant. Baseball is still an unfortunate outlier. Only a few players and umpires became open after their careers ended. That must change if baseball wishes to continue as a national pastime for all people in this country––and beyond.

Baseball Rebels concludes with some observations on today’s baseball activists and an agenda for change. There have always been players with a social conscience and Dreier and Elias note those who came after Jackie Robinson. The Mets’ Tom Seaver was a vocal critic of the Vietnam War. The Blue Jays’ Carlos Delgado mobilized in support of Puerto Rican resistance against the U.S. Navy bombing of the island of Vieques; his hero was the iconic player/activist Roberto Clemente. Many players resisted the abominable Donald Trump, some refusing to stay at his hotel and others declining to visit him at the White House when invited for championship celebrations and photographs. Still others have protested police misconduct and have publicly supported Black Lives Matter actions. The authors make special mention of pitcher Sean Doolittle of the A’s (previously the Nationals). He has been “the most outspoken baseball player of the twenty-first century, even before Trump began running for president.” Fans and general readers alike can learn about this remarkable man who exemplifies the highest principles of the athlete/activist.

Baseball Rebels end by noting that there is an unfinished agenda for the sport. Baseball was never ready for Jackie Robinson; it’s never ready for any unnerving change. Society in general rarely is. So, baseball too must nevertheless accommodate the changes of a multicultural society with different people of different sexual orientations and new world views. And the companion book, Major League Rebels, is especially for die-hard fans and those with sustained and compelling interests in sports and society promoted by path breaking scholars like Harry Edwards and a few others (and powerful journalists like Dave Zirin and many others) and now including Professors Elias and Dreier, is both an essential and thoroughly pleasurable read.

Their extremely valuable start is by placing baseball in the context of American labor history. I know from my personal experience of teaching history that my students know little about the struggles of workers in America. This book moves to correct that deficiency. American capitalism is fundamentally based on greed and naked exploitation of workers, a reality that inevitably included professional baseball players. The authors chronicle some of the major labor struggles of the late 19th century to provide historical context and the disgraceful exploitation of American workers during the Gilded Age and well beyond. Professional baseball players were also subjected to harsh employment conditions. Owners imposed terrible working conditions, regularly cut pay, and ignored their value and mobility.

A brilliant Renaissance man, John Montgomery Ward, attempted to change the picture. Ward was himself a gifted pro player. But he was also a lawyer, linguist, and writer––like an earlier version of Paul Robeson. In 1885, he organized the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players (BFBP). This is a splendid feature of both American labor and baseball history, largely unknown until the appearance of this book. He realized that the reserve clause was inherently wrong, almost like slavery. The owners resorted to familiar anti-labor actions, including using incendiary anti-union rhetoric, cutting wages, bringing in strikebreakers, and resorting to conservative courts. Ward returned as a player, where he continued to excel.

He continued to organize and founded the Players’ League (PL), another radical labor organization. The details of its ultimately unsuccessful struggle are carefully elaborated in the volume and readers should be fascinated with this compelling narration. Eventually, in 1922, the U.S. Supreme Court, in one of its many absurd rulings, held that baseball was exempt from federal antitrust regulation. Ward, who died in 1925, wasn’t inducted into the Cooperstown Hall of Fame until 1964, belated recognition for an American radical.

The BPBP and the PL fell apart in 1890. Several other baseball union efforts likewise failed quickly. It took many decades before major league players had their own labor union and it required superstars including Robin Roberts, Jim Bunning, Bob Feller, Sandy Koufax, and Don Drysdale to facilitate that effort. As noted earlier, Union veteran Marvin Miller joined that effort and the courageous Curt Flood broke the back of the reserve clause. Miller and Flood were truly historic figures whose accomplishments are thoroughly documented in both books.

Major League Rebels also makes an enormous contribution to our historical understanding by detailing the role both of baseball owners and dissenting baseball players in resisting war and fighting for peace. Organized baseball has always been one of America’s corporate cheerleaders for war and intervention, a trusted ally of U.S. imperialism. In World War Two, baseball provided legitimate assistance for morale building for the “good war.” Stars like Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, and Bob Feller joined the armed services.

Vietnam provided a catalyst for objections to war. While the various Baseball Commissioners and some players were uncritical supporters of this monstrous war, others opposed it: Tom Seaver, Jim Bouton, Ted Simmons, Dock Ellis (belatedly), and a few others. It was never a hotbed of anti-war resistance and it never made a significant contribution to the massive protest that occurred throughout the country and the world. Still, it was a crack in the edifice.

The book’s chapter on Latinos’ struggle against baseball colonialism and racism adds another huge component to our more comprehensive understanding of our “national pastime.” Players from Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, and elsewhere have transformed the game’s demographics. By 2020, Latino players comprised about 30% of the active major league rosters and an even greater percentage of minor league players. Many of these players have been truly magnificent stars like Roberto Clemente, Minnie Minoso, and Bobby Avila. The authors, most importantly, show how Latino players broke the ethnic color line in Major League Baseball. America’s racist policies have long oppressed nations and peoples of Latin America and those policies also successfully blocked Latino players from playing baseball in the U.S. for a very long time. In fact, the only Latino players in the big leagues had been light-skinned men able to pass for white. The book chronicles how some Latino players challenged American domestic and foreign policies and prejudices.

The final part of this exciting book profiles baseball figures who decided to become political activists on several issues beyond reforming baseball itself: Bill Veeck, George Hurley, Jim Bouton, Bill Lee, and Sam Doolittle. These men are rarely known to most contemporary baseball fans, whose primary concern is to enjoy themselves and follow the fortunes of their favorite teams. This is perfectly understandable, especially in a pressure-filled society with abundant demands. Still, historical knowledge and perspective are always a welcome because they can add to personal enjoyment while not distracting from the immediate pleasures of the games themselves.

All these baseball rebels decided to take public and often unpopular stands. They were truly rebels for all seasons. A few examples: Bill Veeck voted for Socialist Norman Thomas each time he ran for president. Jim Bouton was an all-star pitcher for the Yankees and wrote the iconic Ball Four in 1970. He was involved in anti-Vietnam War protests, anti-South African apartheid protests, and American racism protests. (Spaceman) Bill Lee was a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox and the Montreal Expos and was widely considered “eccentric.” He protested racism in Boston, journeyed to Cuba, and opposed nuclear power and supported environmental issues, the Equal Rights Amendment, and women’s rights generally. Sean Doolittle, noted earlier, is an activist with the Democratic Socialists of America. Many current players continue this spirit of social commitment and engagement. This is not a trivial pursuit. It shows that baseball players, no less than other people, are capable of active, critical public citizenship.

Baseball is tremendous fun. I played it in my (much) younger days. I still read the sports pages regularly, perusing many box scores. I watch and root for the Dodgers often on television in my adopted city of Los Angeles. But I still most fervently root for my hometown Philadelphia Phillies, suffering regularly from their disappointing performances. These two books have only increased my pleasure as a fan and given me wonderful substance in my role as a university teacher. They have many names and dates––exactly what baseball fans and even academics prefer. Here are two outstanding companion volumes that bring both intellectual satisfaction and just plain enjoyment in reading about baseball. I think again about those Berkeley professors from long ago who thought that sports should have nothing to do with serious academic inquiry. They could never have imagined Peter Dreier and Robert Elias.