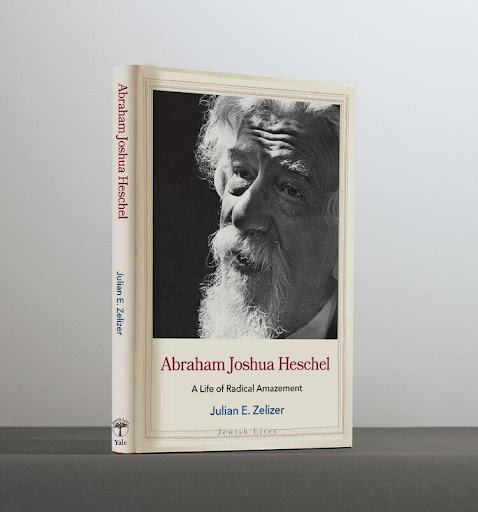

Julian E. Zelizer’s new book, “Abraham Joshua Heschel: A Life of Radical Amazement,” charts Heschel’s life (1907-1972) from his childhood in Poland to his emergence as the foremost Jewish thinker and leader of the movements of the 1960s.

In seven chapters Zelizer traces the life of Heschel correlating geography with biography. Taken on a whirlwind trip, we are transported to Warsaw and Berlin in Europe traversing Cincinnati, NYC, Selma, and Washington in America. The final chapter charts the multi-dimensional legacy of Abraham Joshua Heschel. This is a biography worthy of its subject.

Having been a student of Heschel at the Jewish Theological Seminary for most of the sixties, I lived through much of the book. Through this page-turner, I felt I was revisiting the formative events of my life through an eye-witness. What a surprise to find out that the author was not even alive then. Nonetheless, Zelizer moves nimbly from one dimension of Heschel’s life and legacy to another illuminating everything on the way.

Heschel rose to prominence in the fifties and pre-eminence in the sixties. In about 1962, an Israeli magazine of religious affairs, Panim El Panim, edited by Pinchas Peli, published an article on the three influentials of American religious Jewry featuring rabbis Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Joseph Baer Soloveitchik, and Abraham Joshua Heschel. The article was prescient as the three dominated American Jewry and beyond throughout the sixties and beyond. Each of their deaths produced a cottage industry of books about their teachings and lives that grows as time passes. The death of great men does not mark their end. Au contraire, they grow in greatness. Indeed, the sense of loss deepens as time goes on. I sense it acutely as I may be one of the few still around who was in contact with all three. Soloveitchik went on to become the pre-eminent spokesman of Modern Orthodoxy in halakhic and intellectual matters. Schneerson transformed Habad Hasidism from a Russian-centered contemplative movement into an activist worldwide movement.

Heschel was the scholar-theologian-activist who embodied the ethical turmoil of the sixties. He marched in Civil Rights demonstrations where he became a friend and moral advisor to Martin Luther King Jr. and company, restructured Jewish-Christian relations significantly through his friendship with Cardinal Bea,[1] protested the Soviet discrimination against Jewry inducing his friend Elie Wiesel to go to Russia and author The Jews of Silence, advocated the religious significance of Israel after the 6-day war, and instigated much of the anti-Vietnam War movement along with Clergy Concerned about Vietnam, which he founded with younger comrades including Richard Neuhaus, Daniel Berrigan, and William Sloan Coffin. I recall vividly the foundational meeting in October 1965 at St. John’s Divine Church in NYC.

While a grad student at Yale in the early 70s, I asked Coffin, the then chaplain of Yale University, about Heschel’s impact on the group. He said time and time again we were on the verge of despair regarding our impact on the political scene when “Father Abraham” would walk in demanding to know how many more Vietnamese had died today thereby energizing us with renewed moral vigor to maintain the course of ending the senseless war.

Heschel’s signature move was his response to King’s request of marching together on Sunday in the Selma to Montgomery March of 1965. I heard of this that Saturday night while paying him my post-Shabbat visit. Heschel was already somewhat a theological celebrity among King’s associates. His book The Prophets would be carried around and cited aphoristically like Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book.

Heschel refused to compartmentalize his moral concerns. The fight for the Blacks of America was of one cloth with his fight for the lives of the Vietnamese. This hit me memorably after King delivered his famous, or infamous, anti-war sermon at Riverside Church, New York City, on April 4, 1967. Seeing Heschel emerge from the Church I ran up to him while he was repeating, “I won, I won.” Asking what he won, he responded that he had won King over to the moral and political linkage between advancing civil rights at home and opposing the war in Vietnam. After all, according to Heschel, “to speak about God and remain silent on Vietnam is blasphemous” (p. 187).

Heschel was a master at seeing the broad picture avoiding the blinders of single-focusing. In early 1968, at one of Heschel’s nightly bi-weekly seminars in his office at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, I espied a man in a dark turtleneck sweater wandering the halls outside Heschel’s office. Informing Heschel, he bolted out of the office and brought the man in introducing him as his friend Father Daniel Berrigan. Among my fellow students were three who became significant exponents of Heschel’s thought: Byron Sherwin, of blessed memory, Arthur Green, and David Novak. Berrigan was invited to make his case for Heschel joining him in breaking the law and going to jail. (Subsequently, he burned 387 recruit citations, symbolically using homemade napalm.), Berrigan made his case pointedly using the precedent of Jeremiah who in protesting the war against Babylon was cast into a pit. He contended that we can salvage our moral integrity only by disassociating from the evil government that was daily slaughtering Vietnamese. As long as we benefitted from being free Americans we were tainted, indeed culpable. Heschel queried each of us on what he should do. Then, turning to Berrigan, he asked how many Vietnamese lives would thus be saved. Berrigan refused to entertain the question arguing that the moral imperative now was not to save lives but to save our souls. Piqued, Heschel rejoined that it’s not our souls that we are to save but their lives (the story is nuanced on p. 199). What a privilege to witness a great Jewish-Catholic debate on religious priorities. Such was the pedagogy of Abraham Joshua Heschel. The upshot was, as Zelizer writes, while Berrigan was “clamoring to employ more radical forms of civil disobedience, Heschel… insisted on sticking with legal means” (p. 173).

This survey of Heschel’s life and thought has all the hallmarks of a professor of history and public affairs who fell in love with his subject. Zelizer’s knowledge of Americana succeeds in filling in the blanks while contributing a thick description of his trenchant observations. Interspersed with theological, ethical, and historical observations along with ample citations from Heschel’s writings, the book illuminates both life and thought. The book fulfills both senses of its subtitle “A life of Radical Amazement.” Radical amazement is at the root of his theological perspicuity as well as our response to the multi-faceted life of Abraham Joshua Heschel, poet, survivor, rebbe, scholar, theologian, ethicist, spokesman, and social activist, making him a candidate for the quintessential twentieth-century Jew.

Still, more could be said about Heschel the scholar of Judaism. While much has been said of Heschel’s religious genius and moral courage as a twentieth-century theologian, more needs to be said about his intellectual and scholarly audacity. He challenged the whole academic model of doing the historiography of Jewish theology by offering an alternative reading of the history of Jewish theologizing. In doing so, he contributed as much as any scholar of the twentieth century to the theological understanding of all four pivotal periods of pre-modern Jewish existence: biblical, rabbinic, medieval philosophic, and kabbalistic-Hasidic.[2]

Some comments merit revision:

p. 71, Soloveitchik was home-schooled, not “trained in the finest yeshivas.”

p. 80, Saul Lieberman’s emphasis was on understanding the original meaning of classical rabbinic texts, not “on understanding Jewish Law” (p. 80).

p. 80, Heschel joined the faculty of JTS in 1946, not 1940.

p. 104, Wolfe Kelman was the executive vice president of the Rabbinical Assembly, not “the director of JTS.”

Heschel was a full-time theologian and full-time activist, not “part theologian and part activist” (p. 150). The religious genius of Heschel integrated the contemplative and the activist. What others perceived as either/ or, he saw as both/and.

[1] See Reuven Kimelman, “Rabbis Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Abraham Joshua Heschel on Jewish-Christian Relations,” Modern Judaism 24 (2004), pp. 251–271. Available at www.academia.edu/3812105

[2] See Reuven Kimelman, “Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Theology of Judaism and the Rewriting of Jewish Intellectual History,” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, 17 (2009): 207-238, available at academia.edu/38121104.