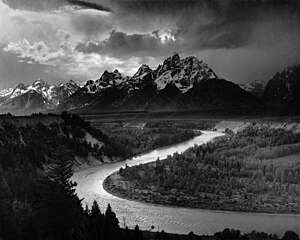

We Americans love grand, gorgeous landscapes of natural scenery. Landscape photographers and painters produce a never-ending stream of pictures of Edenic beauty. We buy images by Ansel Adams — such as this famous view of the Grand Tetons and the Snake River — by the hundreds of thousands, in coffee-table books, calendars, datebooks, posters, and framed reproductions. In magazines, calendars, and publicity materials, environmental organizations use photographs by him and many others.

Most of this art shows the timeless ethereal beauty of nature. It also lacks or minimizes the presence of people. Not everyone likes this sort of thing. New York critics had little positive to say about Adams’s art for most of his career. Landscape art of most cultures in fact include and even highlight humans and their works. Rarely do the credit lines for contemporary landscape art contain names from southern or eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa, or Asia.

The American love of the empty landscape originated among Protestants from northwestern Europe, and especially among Calvinists. Calvinists dominated a swath of Europe from Switzerland through the Netherlands into England, Scotland, and northern Ireland, with substantial support in parts of Germany and France. Calvinism, a.k.a. Reformed Protestantism, was the theology of Puritans and Dissenters in England, Presbyterians in Scotland and America, and Puritans and Congregationalists in New England. It strongly influenced British Anglicanism and early American culture.

Actually, it’s surprising that any art tradition came out of Calvinism at all. Calvinists were notoriously hostile to images, especially in churches. Wherever Calvinists held sway, they removed (sometimes violently) all “idolatry” from religious buildings. In Scotland, scarcely any medieval religious structures remain intact today. Since the Catholic Church had been a major employer of artists and sculptors, they were thrown out of work when the Reformation came.

Calvin did not disapprove of all art, however. Religious and didactic art were OK. Calvinist artists illustrated books and broadsides. Calvin especially commended portraits and landscapes. Portraits depicted humans, the crown of creation. Landscapes depicted creation, the work of God, and reminded the viewer of his power and goodness.

The Dutch were the first to develop a Reformed Protestant art. Calvinists were terribly worried about hypocrisy and lying, so the Dutch developed an intensely realistic style whose minute details were “truthful” to life. Obsession with “truth” would be a hallmark of Reformed Protestant artwork. The Dutch painted everyday scenes that usually illustrated a moralistic point or a popular saying. They also created astonishingly realistic landscape scenes, which, since they were painting the heavily-populated Netherlands, generally included man and his works.

Across the English Channel, the Reformation and the rise of Puritanism scotched the flourishing medieval English artistic tradition. For nearly two centuries, almost all major artists were imported from the Continent, like Hans Holbein or Anthony van Dyke.

English art revived in the 1700s with the career of William Hogarth, a Dissenter. A successful portrait painter, he innovated on Dutch moralistic genre painting and mixed moralism and art in a novel and influential way. Hogarth is best remembered for several popular series of paintings or etchings that illustrated the consequences of vanity, idleness, drunkenness, and other sins. These series were the ancestors to panel cartoons and story boards. Just as important as this innovation was Hogarth’s promotion of young English artists.

One of Hogarth’s students was Thomas Gainsborough. A Dissenter from the former Puritan stronghold of Sudbury, Gainsborough painted superb portraits for a living, but he preferred landscapes. When possible, he combined the two and portrayed wealthy clients on the grounds of their estates. Although he did no satirical paintings like Hogarth, he included a good deal of moral commentary in his paintings. Mr. and Mrs. Robert Andrews of ca. 1750, for example, prominently includes straight rows of wheat on the right. They told the viewer that Andrews had adopted the latest agricultural invention, Jethro Tull’s seed drill, and by good stewardship increased agricultural abundance. A steeple that rises above the greenery in the distance suggests piety, while a barn implies prudence and providence. Gainsborough was the first in the line of great English landscape painters, including Constable and Turner.

In America, Calvinist prejudice against fine art was pervasive. Fine art served merely base, human ends, not godly purposes. No painter did more to convince Americans that art could serve higher, moral goals than Thomas Cole. Cole was born to Dissenters in another former Puritan stronghold, Bolton, England. He came to the United States as a teenager, determined to be a great artist. Religious purposes informed his art. He painted many scenes from the Bible, Milton, and Bunyan and did several didactic, moralistic (and very popular) series à la Hogarth.

Cole’s biggest legacy was his role in founding the Hudson River School of landscape artists. They reveled in wild scenes of New England, the Catskills, and the Adirondacks, which unlike long-civilized Europe showed the direct hand of the Creator. In Cole’s famous Oxbow of 1836, God’s presence speaks from the storm in the wilderness on the left side, while the peacefully prosperous landscape to the right, as with Gainsborough, told of the bountiful stewardship of a godly, moral people. It was a New England landscape, where dwelt the Congregational descendants of Puritans.

After Cole’s early death in 1848, his student Frederic Edwin Church succeeded him as America’s greatest painter. Church was the son of conservative Congregationalists whose Puritan ancestors founded Hartford, Connecticut. His esthetics were shaped by British Presbyterian critic John Ruskin. Although, like Cole, Church sought to be faithful to the truth of nature, he drew from Ruskin the idea that truth meant detailed scientific fidelity to plants, animals, rock formations, and clouds. His often-huge canvases stunned viewers with a wealth of precise detail. In 1857, after studying Ruskin’s works, Church painted America’s most famous natural wonder, Niagara Falls. Perhaps never has water been painted so effectively. Church soon had imitators. After the Civil War, Albert Bierstadt and others discovered the grand unpainted vistas of the American West. They soon out-Churched Church.

But photographers had discovered Yosemite Valley even before Bierstadt and the painters got there. Men like Presbyterian Carleton Watkins and Congregationalist George Fiske took the first photos of many now-iconic views. Watkins’s images circulated in the East and played a role in passage of the bill in 1864 making Yosemite a park. Adams knew and studied his predecessors’ images and in some cases deliberately took pictures of the same views from the same vantage points. Adams said that his style of “straight photography,” with its crisp detail, captured the physical truth as well as a spiritual truth of landscapes. Other popular photographers of Reformed Protestant background, like Eliot Porter and Galen Rowell, followed in Adams’s footsteps. The tradition lives on.

Painting could never be as faithful to the truth of nature as photographs were. By the early 1900s, painters abandoned from the obsessive realism of Church and the Hudson River School. Modernist painters of Reformed Protestant backgrounds expressed the spiritual truth of landscape through abstraction, as in Arthur Dove’s Nature Symbolized No. 2 of 1911, with its suggestion of wind and trees. Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe, all artists in Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, influenced each other on their paths to express the spiritual truth of the uninhabited natural landscape. Their Modernism transmuted old Calvinist values into landscape art for the contemporary world. Later practitioners like Dutch painter Willem de Kooning and Presbyterian artist Jackson Pollack took abstraction even further.

Strict Calvinism was fading in American Congregational churches by the middle of the nineteenth century and in Presbyterian churches by the beginning of the twentieth. Yet the denominational cultures of both churches still fostered Calvinist values. For example, painter Mary Agnes Yerkes, raised Congregationalist, continued through the twentieth century to paint ethereally beautiful landscapes of nature, usually excluding people and their works from the frame. You don’t have to grow up in a Reformed church to appreciate the art of the pristine landscape, but it is no surprise that such a large proportion of the artists themselves did. More than five centuries after Calvin and almost two centuries after Cole, the art of beautiful uninhabited landscape still moves and inspires us.

—

Mark Stoll is author of Inherit the Holy Mountain: Religion and the Rise of American Environmentalism (Oxford University Press, 2015). He teaches environmental history at Texas Tech University.