This mural in Vicksburg, Mississippi, honors the social, political, and religious contributions made by African American residents. Vicksburg was home to Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American U.S. Senator and the pastor of Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Credit: Creative Commons/Paul Lowry.

The majority of African Americans believe in God, and the large number of independent and denominational black churches spread across the United States suggests many of these believers spend Sunday morning recognizing and worshipping God. This is the common story of African American religious expression – black churches shaping the private attitudes and practices of the faithful. Few debate this narrative. More controversial and less easily captured, however, is the public profile of black churches. I don’t mean the private indiscretions of ministers and members made public, nor do I mean efforts to evangelize beyond the walls of a given church building. Instead, I have in mind involvement of black churches in public issues – black churches attempting to influence policy and other markers of collective, secular life.

In raising this issue, my concern is the appropriateness and usefulness of such activities on the part of churches. Are black churches the best (or even a reliable) mechanism for shaping public thought and policy, and for distributing public resources? Simply put, should black churches play a role in shaping the public arena and the public life of African Americans? Many who respond in the affirmative to these questions do so because they frame as a moral failure the challenges facing African American communities, and they promote black churches as the institutions best prepared to address moral and value driven problems. Others, like me, are more cautious in their celebration of “Black Church” involvement in the public arena – arguing instead that churches are best equipped to manage the private, spiritual needs of those who claim membership in them. The public arena of US life requires a different type of discourse and a different range of institutional supports. Because this second response is less firmly lodged in traditional perceptions of black church life, it requires some historical context.

The Development of Black Churches

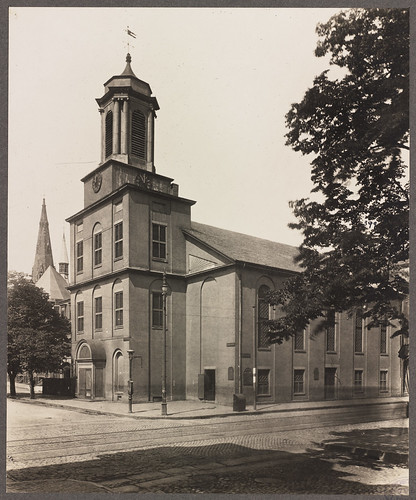

Charles St. Church, an African Methodist Episcopal Church, was built in 1807. Credit: Creative Commons/Boston Public Library

Fueled by the spiritual revival commonly called the First Great Awakening (1730s-1740s), the large collection of independent and denominationally based churches (complete with varying beliefs and practices) that we now label the “Black Church” began to take shape – most notably with the establishment of black Baptist churches in the mid-eighteenth century. These Baptist churches were followed by the creation of Methodist churches – the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and the Colored (turned Christian) Methodist Episcopal Church – during the nineteenth century. The second Great Awakening (roughly 1800-1860s) enhanced the appeal of black churches and their mission. The Civil War gave these churches access to a population of formerly enslaved Africans who desired to establish their independence in every conceivable way – including their religious choices. According to historian Albert Raboteau, prior to the development of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (1816), the Methodist Episcopal denomination claimed roughly 11,600 members of African descent in 1790. Less than a decade later, the number was over 12,215 – representing roughly one-fourth the total Methodist membership. The African Methodist Episcopal Church grew to almost 500,000 before 1900. The African Methodist Episcopal Church Zion had a membership of roughly 350,000 before 1900; and, lagging a bit behind, the Colored (later Christian) Methodist Episcopal Church had a membership of a little over 100,000 by 1890. Some estimates put the number of Baptists of African descent at 18,000 by 1793, and this number increased to 40,000 by 1813. This growth pointed to particular needs for meaningful life, but it also pointed to a hopefulness regarding the ability to secure this quality of life within the United States despite continuing patterns of discrimination.

From their initial development, African American churches typically were optimistic regarding the potential of the United States to live out its most profound principles. And they combined this hopefulness with assurances that hard work and moral correctness would secure full participation in the workings of public life. These churches were promoted as having the vision, capacity and commitment, to point out social and spiritual deficiencies in their members. Although spotty at times and not consistent across denominations, some protestant black churches worked to improve spiritual well being as well as to foster traits and characteristics, as well as moral and ethical postures that were necessary to secure heaven and full participation in the life of the Nation.

While not completely free from the restrictions and hardships associated with slavery and anti-black racism, these protestant churches and emerging denominations during the late 19th century and 20th century were believed to provide space and resources to address a relatively full range of needs. Black churches presented themselves as by and for African Americans – the only institution committed solely to the welfare of that population. And for a good number of years, these churches were the most visible sign of respect for African Americans’ personhood. Within those four walls they had the ability to map out their own life agendas, centering on their desires and wants – but always with an eye on the larger society.

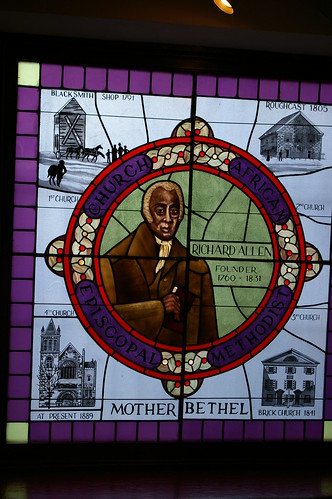

A stained glass window depicts Richard Allen in Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Credit: Creative Commons/Michelle Spomer

As physical manifestation of this function, church buildings served a variety of purposes: locations for preaching the gospel, spaces of spiritual fellowship, schools of morality and discipline, and sites for the advancement of social sensibilities that would ultimately push the larger society to embrace African Americans as equals. For example, Richard Allen, the first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, noted the capacity of these churches to inform and influence both the private – health of the soul – and public dimensions of individual and collective life. His sermons, and those of other ministers, were laced with calls to proper moral conduct – no drinking, proper use of money, and so on – as well as critiques of social injustice.

What early church leaders like Allen and those coming after them preached and encouraged falls into three categories: (1) critique and corrective to the patterns of discrimination impacting African American life; (2) promotion of characteristics, sensibilities, and moral outlook necessary for full citizenship; and, (3) formation and expansion of organizational structures meant to advance the churches’ public agenda. Regarding critique and corrective, the Jeremiad is the most expressive example of this rhetorical style. Noted within the language of slave revolts often lead by preachers – the Jeremiad was a contemporary style of proclamation referencing the Hebrew Bible’s prophet Jeremiah and his denunciations of injustice. But whether used by revolt leaders or less radical ministers, it called attention to evildoers and demanded correction, or destruction would befall the offending group. Tied to this Jeremiad was a sense that African Americans were a “chosen” people with a special relationship to God. For many holding to this thinking, the Civil War and Reconstruction marked the fulfillment of God’s promised redemption through cosmic justice acted out in the public arena of human history.

This war and its socio-political restructuring of the United States ushered in a golden age of religiously influenced African American public life. The mere number of ministers entering local and national politics during this period marked a connection between church life and public policy. Yet, within a short period of time, these same ministers found themselves addressing the nadir of African American involvement in politics as new forms of discrimination and systems of violence subdued their engagement with the socio-economic, political and cultural workings of the nation’s public arena. This change occurred despite changes to the legal status of African Americans through the 1867 Civil Rights Act (and that of 1875) that gave African Americans the right to vote. Along with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, such legislation gave the impression of a new political day – but there was little that actually supported this impression.

Despite their disillusion with the political climate and failure to develop an effective counter-response to it, black churches, nonetheless, continued to work and grow. For instance, some scholars estimated that there were roughly 500,000 African American Baptists before the turn of the century, and this number grew to over one million before the end of the first decade of the twentieth century. The total number of African American Christians by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century reached close to four million. Infrastructure to support this growth also advanced. For example, the number of African American Baptist ministers increased from almost 6,000 to roughly 17,000 in the sixteen-year period between 1890 and 1906. It’s a mistake to think that this infrastructural growth meant Methodists and Baptists were the only religious game in town. The beginning of the twentieth century marked by Jim Crow racial restrictions and customs also framed a new spiritual energy concerned with sanctification and holiness. And this development pointed in the direction of public life because adherents argued that the decline of the United States witnessed through the bloodshed the Civil War resulted from a rejection of God’s will and God’s requirements for human life.

For black churches this loss of life pointed to more than political struggle. Moral failure was the underlying issue. In response to this predicament, churches sought to buttress the best values and morals of the faith over against what they perceived as the moral slippage marking so much of the nation’s activities and thought. To get the nation back on track, citizens had to rededicate themselves to righteousness and purity of thought, word, and deed. For some this turn to holiness was insufficient in that it failed to recognize the ability of Christians to live life marked by spiritual perfection, with a range of physical connotations. Those pushing this theological position looked to the gift of the Holy Spirit associated with Pentecost as an aid in the living of a faithful life in the contemporary context of the United States. Through this experience drawn from the biblical book of the Acts of the Apostles the faithful fueled their desire for spiritual perfection, and this was given institutional force through developments such as the Church of God in Christ (the largest African American Pentecostal denomination in the country). It is commonly believed that this push for perfection came at the cost of limited concern for socio-political issues. However, concern with spiritual perfection marked by “speaking in tongues” and energetic worship did not rule out involvement in public issues. To the contrary, attention to inner spiritual wellbeing often was connected to a critique of racial discrimination in that right relationship with God demanded proper conduct in one’s mundane life.

Whether Methodist, Baptist, or one of the more recently developed denominations, black churches focused much of their public efforts on enabling and facilitating the “Great Migration” – the large-scale movement of roughly seven million African Americans out of the rural south and into cities in the North and South, and Western US. Significant relocation of African Americans brought a variety of challenges needing attention. For churches taking up these challenges Christian responsibility entailed a blending of public involvement and spiritual development captured in the phrase the “Social Gospel.” Manifestations of this understanding of Christian commitment included churches working to incorporate new arrivals by establishing programs to address their socio-economic, recreational, and political needs as well as educational opportunities including lessons in moral conduct and ethics for the urban context. Over against the efforts of some, many urban churches found their resources inadequate to meet the financial needs of the new arrivals and the maintenance of their longstanding financial obligations. In addition, the cultural differences between migrants and African Americans with a more established relationship to the urban context created tensions in terms of worship styles, social attitudes and styles of social conduct. Churches feeling this pressure and seeking an alternative approach to their involvement with new arrivals claimed primary obligation to spiritual growth as the role of the Christian church. The former is typically called the “in-worldly” response to African American needs, and the latter the “other-worldly” response. Albeit different in a variety of ways, taken together these two orientations spoke to shifting perceptions of churches’ involvement in public life. And while they may come across as rigid, these were not fixed categories. The line between the two was flexible and blurred in that churches easily moved between versions of these two responses based on shifting perspectives of pastors, pressures from constituents, and so on.

Whether concerned with the politics of individual salvation, the mundane politics of racial advancement or some combination of the two, black churches assumed that no transformation of any type – spiritual or physical – within African American life could happen without their input. But despite this confidence, it became increasingly clear that religious organizations were not the only option. Secular organizations such as the NAACP and the National Urban League staked a claim as well. But these two did not entail the most graphic challenge to the dominance of black churches in public life. For that one must turn, for instance, to the 1920s when the radical politics of the Communist Party inspired a small but vocal group of African Americans to reject the church on grounds that it was committed to a theology of subservience, had little understanding of the workings of capitalism and class structures, and spiritualized life as opposed to addressing the fundamental cause of dehumanization. Furthermore, the activities of Marcus Garvey during the same period of time also drew energy away from black churches by providing alternative outlets for political expression revolving around Pan-Africanism and cultural nationalism. Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) guided the largest and most elaborate mass movement of African Americans in US history. And while this movement flirted with religiosity, it remained more easily identified as a racial pride and consciousness movement tied to African American participation in Africa’s rebirth.

Black Church Morality in Public

Organizations such as the NAACP and Garvey’s UNIA meant that churches did not own the language of public discourse and that they were not the only structures available for promoting the mundane concerns of African Americans. “Freedom,” “destiny,” and “personhood” remained important components of in the lexicon of life, but the discussion and meaning of such concepts became difficult for churches and church leaders to predict and control. Church codes and creeds of morality and ethics took a blow – not fatal, but substantial. The socio-political landscape of the mid-twentieth century gave black churches the opportunity to push again for public significance as churches argued that their role in the civil rights struggle was irrefutable evidence of their centrality to African American collective life. Montgomery became the calling card of black churches, and is used to mark out the start of the modern civil rights movement.

Participating churches provided use of their physical space, financial resources, services (such as carpooling), and a language of religiously infused justice to guide the protest activities. While not the first nor the only church leader whose participation gave moral-ethical insight and theological framing to mid-twentieth century protest, Martin Luther King, Jr. is commonly referenced as the most prominent leader – the one whose perception of the United States and its democratic potential offered the logic behind civil struggle and legitimized the sacrifices made by advocates of social transformation. Non-violent direction action, the willingness to absorb violent attack, King argued, gave protesters the moral high ground and their persistent use of this strategy would prick society’s conscience. This combination of morality and activism would result in significant change, the end result being a society in which all participated equally as full citizens, with all the accompanying rights and responsibilities. Perhaps what best captured the synergy between the morality of black churches and their ethical commitments brought to bear on the dynamics of public and private life is found in the concept of the Beloved Community first presented by philosopher Josiah Royce, but popularized in the United States by King. By this concept King meant to mark out cooperation, mutuality, and shared socio-political and economic opportunity based on the morality of the “Golden Rule.” As part of the discussion of the Beloved Community, its advocates urged personal conduct consistent with the teachings of the Christian faith and political conduct that recognized the humanity of every citizen. In a general sense, this concept of togetherness worked to bind morality and economics – but it did not satisfy all.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X meet before a press conference. Both men had come to hear the Senate debate on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This was the only time the two men ever met. Credit: Creative Commons/Marion S. Trikosko

For instance, growing tired of beatings and limited gains, some members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in line with King’s philosophy of protest began arguing for a more aggressive approach – one that recognized the potentiality of counter violence to achieve the desired political transformations. The moral high ground, they pointed out, was of limited consequence because recognizing what is right and wrong did little to actually alter the systemic structures of oppression being put in place by white supremacy advocates. The situation would only change substantively when a force equal to that oppressing African Americans countered discrimination and challenged it through equal aggression. Malcolm X became the symbol of this perspective, particularly in northern communities where the techniques of discrimination differed from those in southern states. However, some African American Christians saw no need to pick between Malcolm X and King. Instead, a synthesis between the social theory offered by Malcolm X and the theological-religious values of the Christian faith were brought together within a framework of black consciousness. This combination served as the backdrop for black liberation theology and its concern with a radical shift in the fortune of African Americans as the essential nature of the Christian Gospel. Although much debated and misunderstood in recent years, black liberation theology and its advocates do not hate the United States and are not involved in reverse racism. Rather, black liberation theology pushes for a deep reliance on the demand for equality and transformation of human relationships in line with what it finds expressed in the New Testament accounts of Jesus’ teachings. Yet, while this theology has found a home in academic circles and has inspired the ministry of some church leaders and the vision of the faith held by some church members, by and large it has had limited impact on the thought and workings of most black churches.

During the 1970s and 1980s, when black theology was taking shape, black churches took a hit. Their reputations were soiled because even as civil rights gains did not eradicate poverty and discrimination, and the response of churches to the situation seemed anemic. However, disillusionment with middle class aspirations produced by the continuing impact of discrimination along with a desire for cultural connection brought some African Americans back to churches in the 1990s.

By the time sociologists C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence Mamiya’s published their study of black churches (1990), the average black church had a membership between 200 and 599, and had an average annual income of more than $50,000. A noteworthy percentage (40.8) of urban churches had some type of relationship to civil rights organizations, suggesting that these churches had a sense of public ministry involving the socio-political challenges facing African Americans. Furthermore, according to the 1999-2000 “Black Churches and Politics” survey, and analysis of this survey by scholars such as R. Drew Smith, over 80 percent of those responding to the question indicated that their congregation had been involved in political activism such as voter registration. However, this same survey found that of those indicating their congregations were very politically active during the civil right movement (25%), a much smaller percentage (15%) indicated their churches were very active during the 1980s and 1990s.

The Limits of Black Church Public Vision

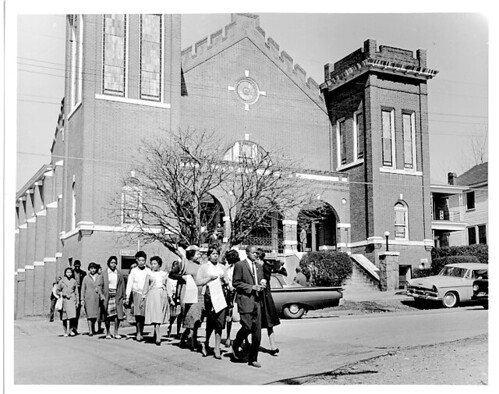

African-American civil rights demonstrators parade before Zion Baptist Church in 1961. Credit: Creative Commons/Richardland Library

Mindful of the sweep of Black Church history presented here, should these churches have a significant role in the public arena, and should they serve as a major mechanism of delivery for public resources? No, and here’s why.

From early church leaders to figures like Martin L. King, Jr., activism has been a part of Black Church existence. However, this same history points out the limits of this activism – the manner in which its theological under pinning has hampered perceptions of democratic life inconsistent with their creedal teachings. People need moral vision strong enough to push against efforts to dehumanize them and their communities. And, churches provide a system that might accomplish this with respect to private life. However, the public arena requires something more than a private system of values and morals. The assumption that the major problem facing African Americans is a moral failure is a fundamental misunderstanding. Morality arguments fail because they assume a type of deficiency within African Americans rectified through imitation of the dominate population, when it is more likely that the problems with which African Americans wrestle are a direct result of the larger population’s values and moral commitments, and political opinions – all of which are bound up in the nation’s long racial history. Assumptions that, on the one hand, African Americans have slipped away from the old moral standards that once preserved them, or, on the other hand, that their moral values in a significant way run contrary to the normative morality of a larger society are both inaccurate, saying more about cultural assumptions than about the actual causes of the socio-economic and political dilemmas currently faced by African Americans.

Morality arguments fly in the face of a history of socio-economic and political disadvantage that shapes and guides the conditions of life for African American communities. For example, an “Economic Mobility Project” study clearly indicates that neighborhood poverty, and exposure to poverty, significantly impacts the long-term mobility of African American children. And according to a recent Pew sponsored study, exposure to poverty is a key factor in the gap between the mobility of African Americans and that of white Americans. Poverty also informs other issues such as educational achievement, attitude, and perception of human potential. This is not a cultural issue, and it is not a result of moral fortitude. It is a matter of economics. Attention to the impact of poverty on individual and collective life does not wipe out accountability and responsibility for conduct; rather, it is to recognize the context for behavior. It is to acknowledge the manner in which economic environments inform and shape options.

Churches do not necessarily see it this way because they tend to shape public discourse using frameworks of “sin” as moral standing, with even the most “earthy” depictions of African American problems under girded by a spiritualization of the public sphere. Drawing on the words of scripture, non-activist African American Christians believe that “we wrestle not against flesh and blood but against powers and principalities…” In this way, many black churches speak and work based on an assumption of pathology – a failure to conform to rules and regulations of life couched in the Bible. And this framing of public life is further troubled by the tendency of churches to establish an “in” group (i.e., those sharing the religious-theological sensibilities of a Christian community) and an “out” group (i.e., those outside the theological and ideological sensibilities of a Christian community). This is religiously induced xenophobia and it serves to polarize. Significant chances for transformed public life are stymied by this arrangement.

Consequently, churches have a language and grammar too narrow for public exchange and discourse and no good way of thinking through the distribution of resources.

St. Peter Claver Catholic Church Gospel Choir performs at a Juneteenth celebration in Lexington Park, Maryland. Credit: Creative Commons/Elvert Barnes

In fact what they offer is a set of private morals and values. These work within the confines of private organizational engagements such as the internal life and workings of church communities, but they do not serve well when competing claims must be recognized and worked through with respect and without the rigid boundaries of any particular religious creed. Public discourse and public policies cannot secure the best of our democratic traditions if they are based on a privileging of particular religious teachings and practices. The public life of the nation must be more than the highlighting of a particular organization’s thinking and agenda.

This is not to suggest that the public arena is value free. Instead, I am suggesting that the Black Church – and religious organizations in more general terms – are too limited ideologically to provide a system of values sufficient to meet the needs of a population extending beyond their membership and immediate communities. The ability of churches to meet localized needs such as those covered through the limited construction of housing, or the supply of foodstuff, etc., does not equate to their having capacity to address wide-ranging regional and national issues.

It would be wise and more effective to discern and treat the systemic threats to African American advancement and then address them through public programs and resources distributed and supervised by public institutions creatively arranged and monitored.

The organizations comprising the Black Church today do not have unity of vision necessary to generate a workable agenda. Furthermore, because so many well established churches are commuter churches, their capacity to appreciate and respond to the complex needs of those they seek to assist is compromised. The assumed intimate connection between churches and communities may not be in place and the methods of addressing urban concerns offered by churches could easily be out of step with the actual nature of the issues and the complex needs of the population. The language and practices of private morality keep Christians in line with their religious community and mark out how that community approaches life. But this doesn’t translate into a strategy for arranging secular life for a population extending well beyond the community of believers.

The Difference Between Private and Public

Public life is thick and complex, and so theologically inflected moralizing, or publicly funded missionary impulses actually do very little to uncover and address the complexities of African Americans’ public presence in the United States. These religious interventions, no matter how comforting and salubrious they may be to certain segments of the population, hit a glancing blow on the larger social justice and economic problems facing African Americans in the early twenty-first century. They fail to provide a comprehensive, fully formed response to the current climate.

The key to addressing the challenges facing African Americans has to be structures of engagement, robust strategies for communication, and recognition of the complex systemic strictures to progress. The financial resources for such actions, however, should not result from a privileging of church bodies – or religious bodies in general terms – by government. Such funding can blur the line between church and state, damage the secular tone and texture of public conversation and debate, and set-up principles and norms that are narrow and shadowed by the idiosyncrasies of church doctrine. The concern here is not how particular types of activity in the public sphere – through the securing of governmental resources – might limit the prophetic mission of churches by hampering their ability to critique and challenge, to be “prophetic.”

A surrender of care to religious organizations is a problematic move that renders those most in need of assistance vulnerable to the theological whim and spiritualized parameters of organizations. Churches have always spirituality as an underlying dimension, and this is a ministerial ethos too narrow and too restrictive to be useful. Churches should do as they like within the private arena of their particular believing community, but the public arena should be guided by secularity that recognizes the private merit and focus of religious commitment.

Church activity does not replace the requirement of government to establish ways to bring public resources to bear on public problems. The early conditions of African American life are based upon these secular developments only coated with a religious covering. And they can only be countered and corrected through public resources, not church-based morality. What we need at this point is a greater commitment to systemic change, to creative application of public resources to large-scale problems as opposed to holding socio-economic issues hostage to political maneuverings.

There are limits to current strategies that continue to draw from some of the worst thinking about African Americans, but this does not mean a surrender of public issues to black churches – any churches really. Instead it requires commitment to new mechanisms of delivery, new strategies for wise use of public resources, and clear thinking on the true nature of poverty and impoverished life. Anything short of systemic alterations, the use of public resources through organizations and programs not beholden to particular theological positions, is to put a bandage on a gapping wound. To put the burden for improving quality of public life for African Americans on private organizations such as churches not only hides the problem by individualizing what are systemic issues, but it may also result in a surrender of government accountability and a reduction in public resources used to fight issues such as poverty.

Anthony B. Pinn is Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor of Humanities and Professor of Religious Studies at Rice University (Houston, TX). He is also the director of research for the Institute for Humanist Studies (Washington, DC).

Humbly, I differ with the author’s conclusion. We do need the voice of the Black Church as a prophetic, loving voice, giving us an imagination for the Beloved Community.

Dr. King certainly did address the questions of public economics and matters of justice. His Riverside Church speech on Vietnam deserves to be remembered more that the “I have a dream” speech.

Malcom X, from his tradition, did a great favor in not allowing us an easy, sentimental love and justice.

Of course, I also welcome humanist voices as well, in addition to, not a replacement of the Black Church

I always spent my half an hour to read this webpage’s posts all the time along with a cup of coffee.

does anyone or any group at all have any right to influence anyone, or any centers of power? perhaps it woud be better if the slaves and people attempting to graduate from slavery settled for being as invisible as their masters would like them to be. in the case of abolishing the voices of those who we disagree with, who haven’t as much ‘education’, as we do, are not professors, let us instead inoculate those people with shots of materialist positivism and atheism. Why not? Also, take all of their music and their presence in probably our greatest diplomacy and export-their music, so that it will never be heard or publicized again,

if the national rifle association can voice, so can black people’schurch.

If Dr. Pinn’s nalysis is true, it is a sad commentary of how the Black Churchs have lost the biblical cutting edge of prophetic challenge to the systems of injustice that Martin Luther King so well understood and lived out (as did so many Black church-attending students during the courageous beginning of the Civil Rights Movement). But let us be clear: for the most part Protestant and Catholic communities of faith have never understood their own prophetic theology and enacted it in the public sphere. Personal exceptions in such communities have often been ostracized. To some impressive degree, The Unitarian-Universalist and The United Church of Christ (UCC) have been the denominational exception., thank God.

There are actually plenty of particulars like that to take into consideration. That could be a nice level to bring up. I offer the ideas above as basic inspiration however clearly there are questions like the one you convey up the place a very powerful thing will probably be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if greatest practices have emerged round issues like that, however I am certain that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Each boys and girls really feel the impact

Your historic and cultural analysis go a long way to call for the kind of commitments, in the Church and in government practices, that will lend itself to change.

“. . . Anything short of systemic alterations, the use of public resources through organizations and programs not beholden to particular theological positions, is to put a bandage on a gapping wound.